by Dr Amanda Thomson

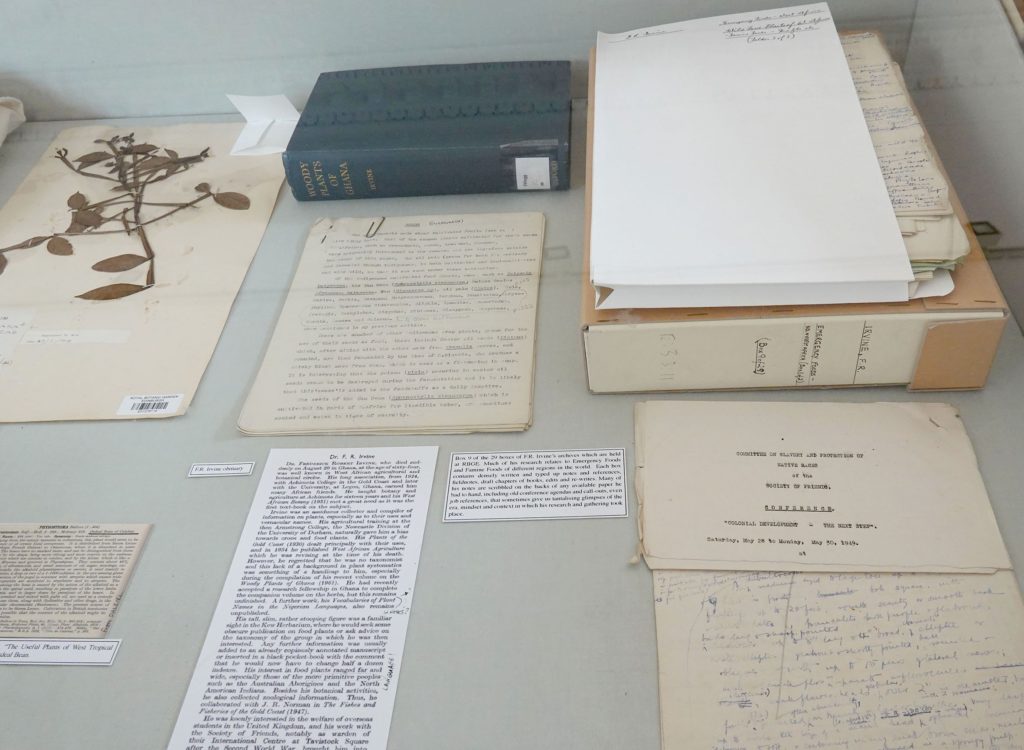

I was sitting in the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh Library, looking through F.R. Irvine’s archive boxes. Irvine was a botanist who was born in Northumberland in 1898 and died in Ghana in 1962, spending much of his adult, professional, life there. His archive consists of 29 cardboard boxes, each packed with densely written notes and drafts for chapters of books, fieldnotes too – a mixture of the handwritten in pencil or pen and typewriter typed, the stained indents of rusted paperclips evident in some of the corners. Torn sheets of foolscap paper are frayed and yellowing, smudged and softened by time and the human hand. Box 9, titled Emergency Foods of North and West Africa (Box 1 of 2), held among other things a paperclipped sheath of papers on ‘West African Famine Foods’ and a foolscap page of notes on B Vitamins in African Fermented Foods, dated 22/9/45 and written in blue ink, a couple of blue splodges of ink in the middle. It’s something, in this day and age, to be able to sit and look at how research was done in the era before computers.

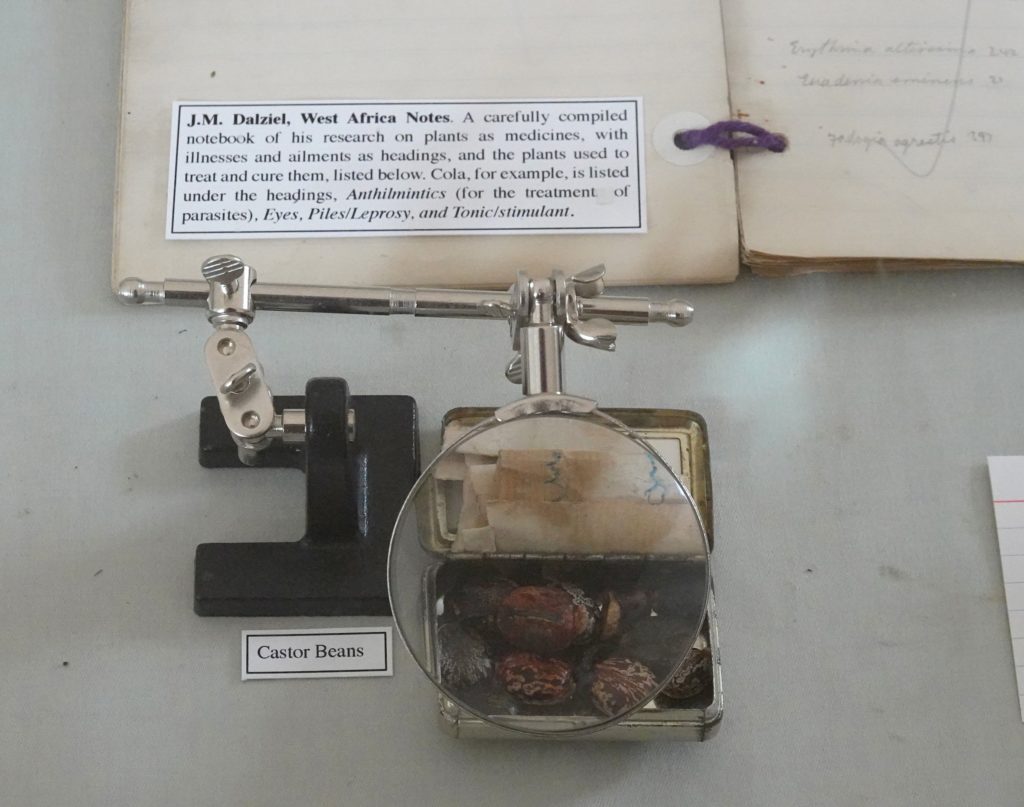

I came across F.R. Irvine through research that I was doing for the Garden’s Silent Archive exhibition which took place in the Garden’s exhibition space, Inverleith House, earlier this year. I’d happened upon F.R. Irvine out of an interest in Western Africa. I was just about to go to Ghana on a writing residency and was thinking about the relationships of botanical gardens to British colonialism and empire and wondering what the Garden’s collection held. In the Library I’d come across J.M. Dalziel (1872–1948), and his fascinating books, A Hausa Botanical Vocabulary, and The Useful Plants of West Africa. The Archive holds his carefully handwritten notebook of West African plants, listed alphabetically, with their uses, medicinal and otherwise, written under their names, which must have acted as a source for his books.

Both Dalziel and Irvine seem like an interesting continuation of a trajectory of the Garden’s links to West Africa that may have started with Archibald Hewan (1832–1883), who has been written about in a previous story, and I’d been looking at the specimens held in the Garden’s herbarium that he’d sent from West Africa. Hewan was born on a sugar plantation in Jamaica, his parents were people of African descent, and his grandfather was the white Scottish owner of the plantation. Carrying this undoubtedly complicated personal history, he travelled to Scotland to train in medicine. From there he went to the Old Calabar Mission, in what is now southeastern Nigeria and practiced there as both medic and missionary. I wonder, for all the factual information that we do have about him, about the raw experience and realities of his life as a person of colour, even the circumstances behind his lineage, and what it must have been like to have experienced the realities of the transatlantic slave trade, enslavement and colonialism first hand. How did he understand empire and colonialism and a Christian mission which from today’s perspectives we see as part of the imperial agenda to conquer, convert and exploit? And how would he have been seen and perceived?

The Hewan specimens that are held in the Garden’s archive were gathered during an expedition to Fernando Po, which is an island now called Bioko and part of Equatorial Guinea. They’re specimens of ferns, flattened, delicately filigreed, on beautifully thin, pale-blue paper. Some specimens hold a cluster of compressed and flattened roots at their base. His love and fascination for botany is clear from letters Hewan wrote to the Garden’s then Regius Keeper, John Hutton Balfour. The accompanying text on each of the specimen sheets is scratched in ink-nibbed spidery writing and states Fernando Po, Dr Hewan, 1862, and even this tells us so much too – the very name of the island points to its colonisation by Spain, then Portugal, and there’s a history related to both enslavement and anti-slavery that the island holds.

The archives of the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh are full of the voices of Black people and people of colour – with a collection of plant specimens from all over the world, how can they not be? But these voices are often hidden or unheard. Who taught Dalziel the language of Hausa and acted as translator? Who helped Hewan learn Efik? In one source I read that Irvine’s co-collector was an A.O. Ohene, a Ghanaian of the Akan people, but I don’t seem to see his name attached to any specimens or on the lists of collectors.

For a series of etchings I made for the Silent Archive exhibition, I focused on plant specimens held in the Herbarium that in some way were related to the transatlantic slave trade and the Middle Passage, and the complex movements and migrations (forced and otherwise) of people, goods and plants. Species like Tamarind and the kola nut were used to make the water more palatable on the ships that travelled the Middle Passage. Castor beans were taken over from Africa and became a plantation commodity, used for lamp oil and nutrition as well as to treat various ailments. Another plant I focused on was bitterwood. Its Latin name is Quassia amara, named after Graman Kwasi (Quassi) (c.1692–1787), who carries his own complicated history. Kwasi was known as a healer on a sugar plantation in Suriname in South America. It’s thought that he was enslaved in and abducted from Ghana (the coastline that Europeans then called the Gold Coast) and taken forcibly to Suriname. He may have recognised and used the plant in South America after recognising similarities to the species that would have been familiar to him in West Africa. It doesn’t need saying that he’s one of the few Black African botanists of that time to have been acknowledged in this way, in honour of his knowledge of this plant. One of the specimens of the plant held in the Garden’s herbarium was collected by Irvine himself in April 1933. His notes tell us that it is a shrub which grows up to 10 feet high, with reddish veins and bright red flowers, ‘very showy’, and that it is also used for medicinal purposes, mentioning ‘quassia chips’. Bitterwood has been used against parasitic worms, diseases like malaria, to combat ulcers, headlice, and its insecticidal properties have been utilised too. It is also, perhaps, one of the ingredients of Angostura bitters.

As I looked at Irvine’s notebooks, and those of Dalziel before him, I could only speculate about who the people were who held the information about the plants and their uses and who would have, probably generously, imparted their knowledge? Who were the healers, the custodians that would have held the knowledge, probably passed down over generations? What were the family remedies that were passed down and shared? And from that knowledge, what have become constituent elements of the medicines and materials that are part of what we all use and take for granted today?

In display cases in the Silent Archive exhibition I showed Irvine and Dalziel’s notebooks and research, trying to ask some of these questions. Sonia Mehra Chawla’s work dived into the history of jute and its complicated and troubled relationship to colonial power and political struggle. Her work included a wonderful film of a jute mill in Kolkata, where the machines still used were made in Glasgow. Annalee Davis explored the links between Scotland and Barbados in the context of the troubled legacy of slavery and deportation and the provenance of the botanical specimens sent from the West Indies to the UK’s Botanical Gardens. Shiraz Bayjoo’s work explored similar themes in relation to Mauritius.

Keg de Souza’s 2023 solo show Shipping Roots at Inverleith House, traced the stories of the Eucalyptus plant, taken to India from Australia by the British and since exported around the world, for good and for ill. She asks the question, “what happens when these trees are removed from the Aboriginal land they grow on and from the Traditional Custodians who care for them?”

It’s so important to try and connect the different parts of the collection together and to join what’s held in them back to the outside world, and fascinating to see how those engaging with the collection do so. It can be like looking for pieces of a jigsaw to put together, without necessarily knowing what the final picture might look like or knowing that there will be many iterations. Collections such as those of the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh are not neutral, nor are they silent, if we start to look. They allow us to look at the past to help us understand where we are now, and looking at them from today’s perspectives can shed important new insights into what has gone before.

Written by Dr Amanda Thomson www.passingplace.com

Belonging: natural histories of place, identity and home is published by Canongate Books