In the spirit of Black History Month, we are sharing the story, otherwise untold, of Dr Archibald Hewan, a 19th century Black doctor and naturalist. Born in Jamaica in 1832 Dr Hewan studied botany at the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, establishing a link with the Garden that still exists today in our herbarium and archives.

Archibald Hewan was born a year before the Slavery Abolition Act 1833 and grew up on the Hampden sugar plantation, St James, owned by the Scottish Stirlings of Keir. His parents Ann and John were both people of colour. Ann was of African and European heritage and was one of at least six illegitimate children fathered by Archibald Stirling the plantation owner.

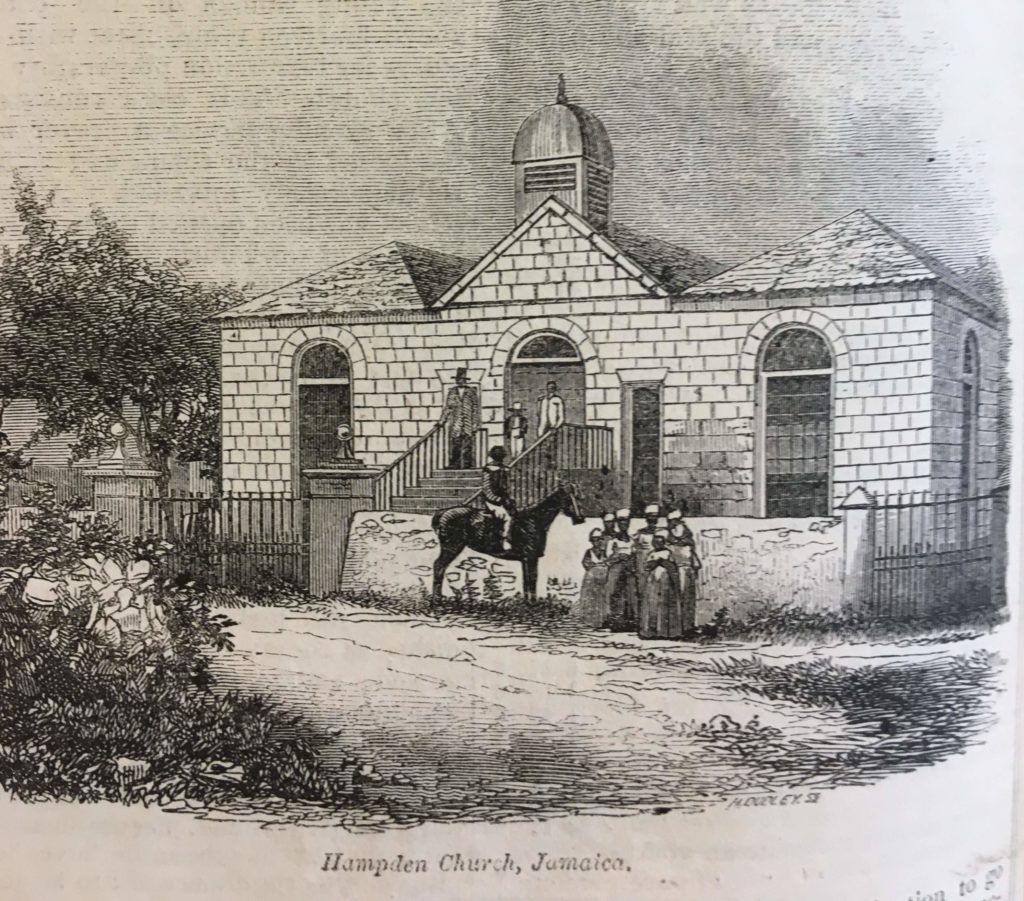

Unlike previous generations of enslaved and free children at Hampden, Hewan was able to attend church and gain an education. His grandfather Archibald Stirling had returned to live in Scotland and paid the Scottish Missionary Society to establish a church (1828) and school (1831) at Hampden. This was typical of the ameliorative initiatives of enslavers in response to mounting pressure from abolitionists.

The young Hewan spent his youth among the Black congregation at the plantation. Then at the age of 19 he travelled to Britain with the assistance of the Missionary Society to train as a doctor, lodging in Glasgow as a student in St George’s Street. A letter he sent to his uncle William Stirling, the heir of the Hampden plantation, was dismissed as begging and there is no record that he ever received a response.

Hewan began his medical training in the early 1850s at the Anderson’s University (now University of Strathclyde). He was examined by the Royal College of Surgeons Edinburgh, and in 1854 was awarded a licentiate to practice. A year later, he left for Old Calabar, west Africa, what is now Nigeria. There, at the Mission of the United Presbyterian Church, he established a thriving medical practice and was reputed for his skills as a doctor and preacher.

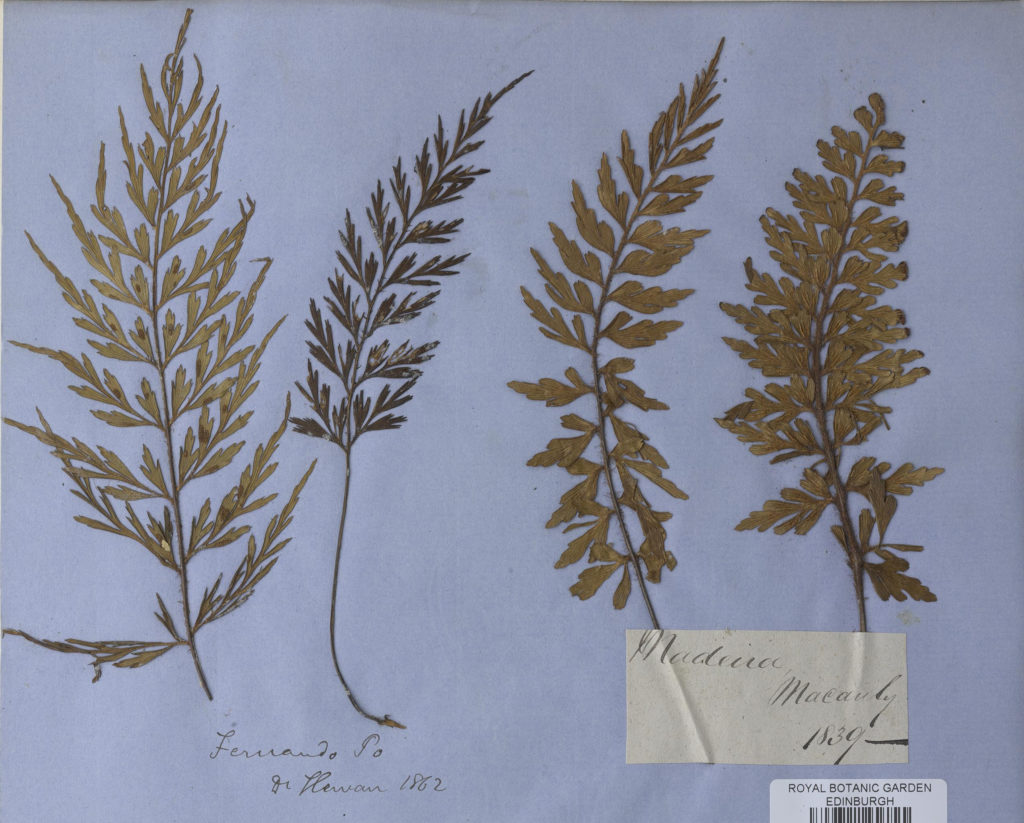

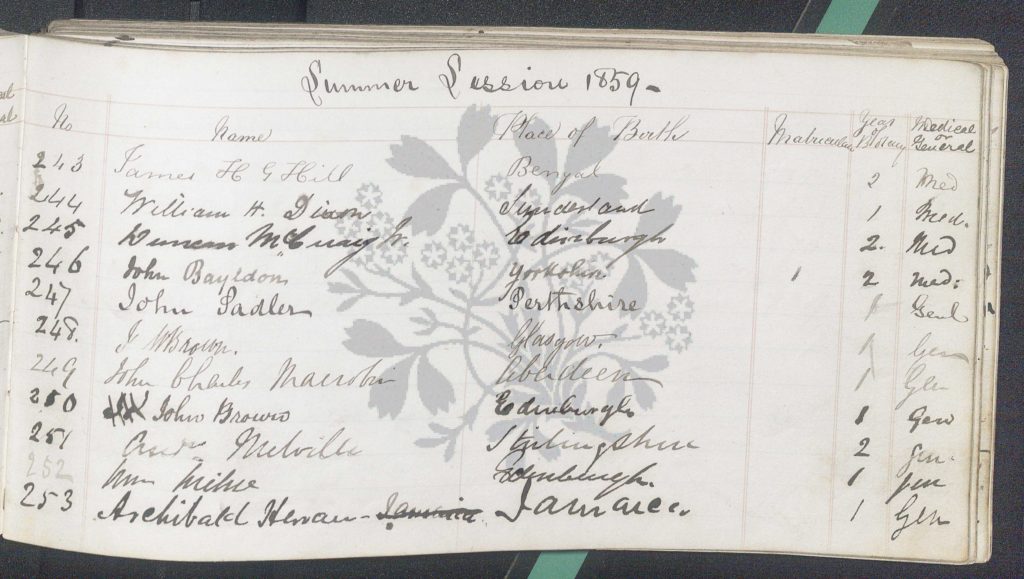

Dr Hewan returned to Scotland in 1859 because of ill health and, during that year, he began to study Medicine at the University of Edinburgh and to attend botany classes at the Garden. There, he met Regius Keeper Professor John Hutton Balfour, who was also the dean of the medical faculty at the university, a connection that would lead to the exchange of letters and plant specimens which we hold in our archives and herbarium today.

In 1860 Dr Hewan married Isabella Elliot, a white Scottish woman, daughter of the Reverend Andrew Elliot, and she accompanied him back to Old Calabar so that he could continue his medical practice with the Mission.

His achievements in Old Calabar included successfully lobbying for the establishment of a small hospital to accommodate African patients, many of whom travelled long distances for medical assistance. By 1861 Dr Hewan had become familiar with the Efik language, enabling him to build up a large outpatient practice attended by ever-growing numbers of local people seeking his help.

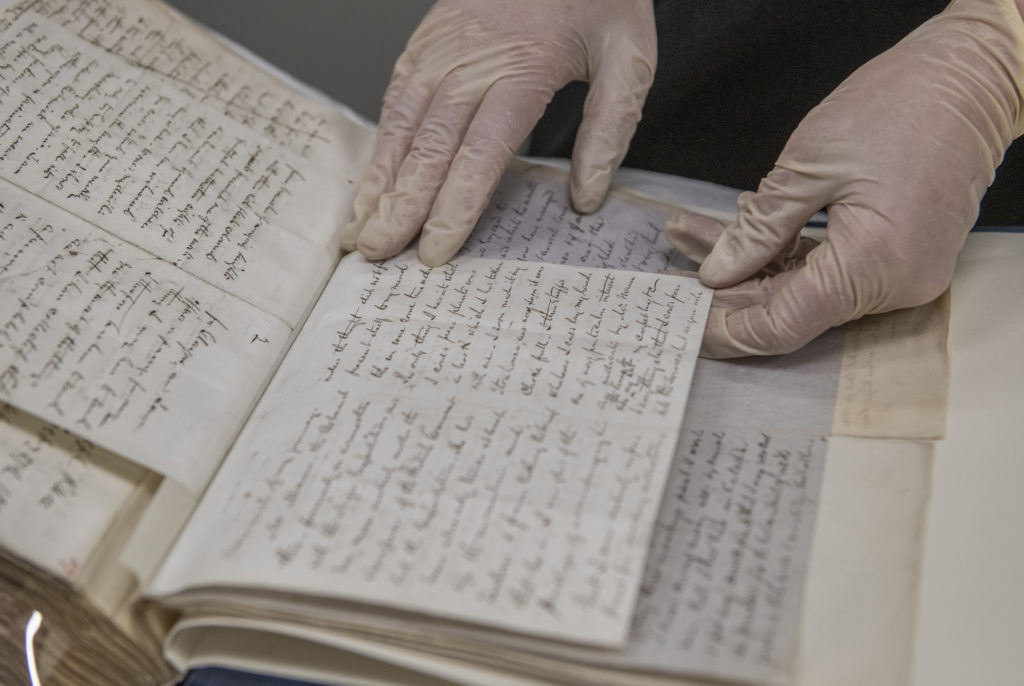

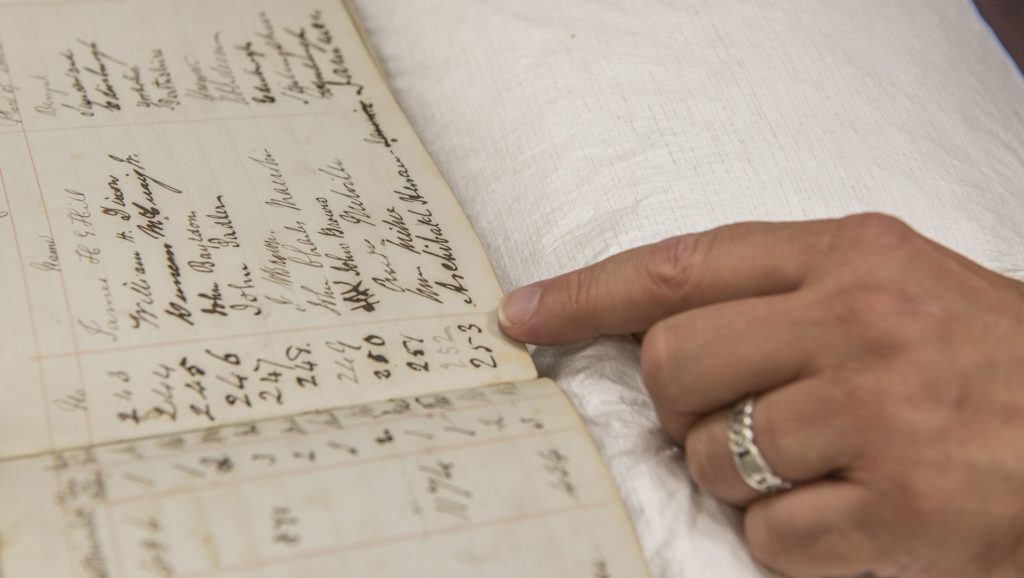

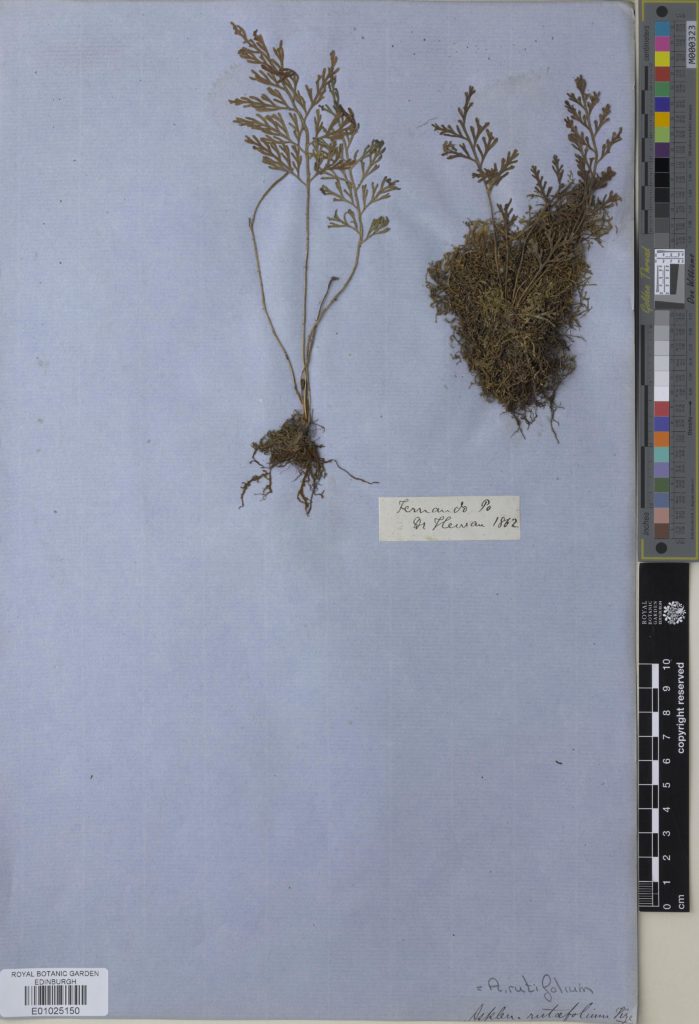

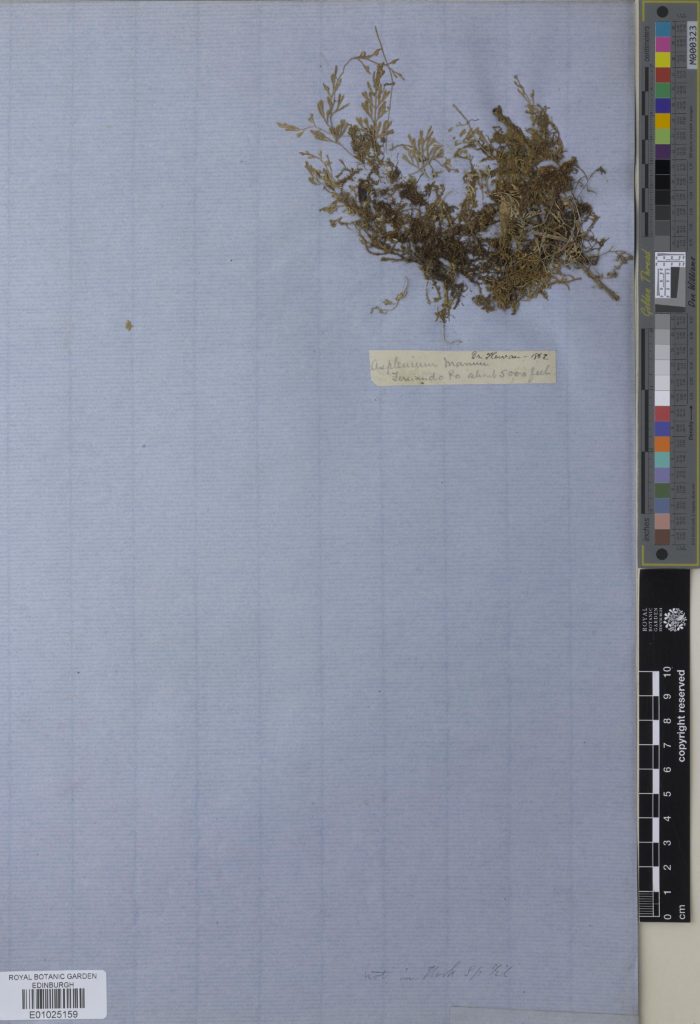

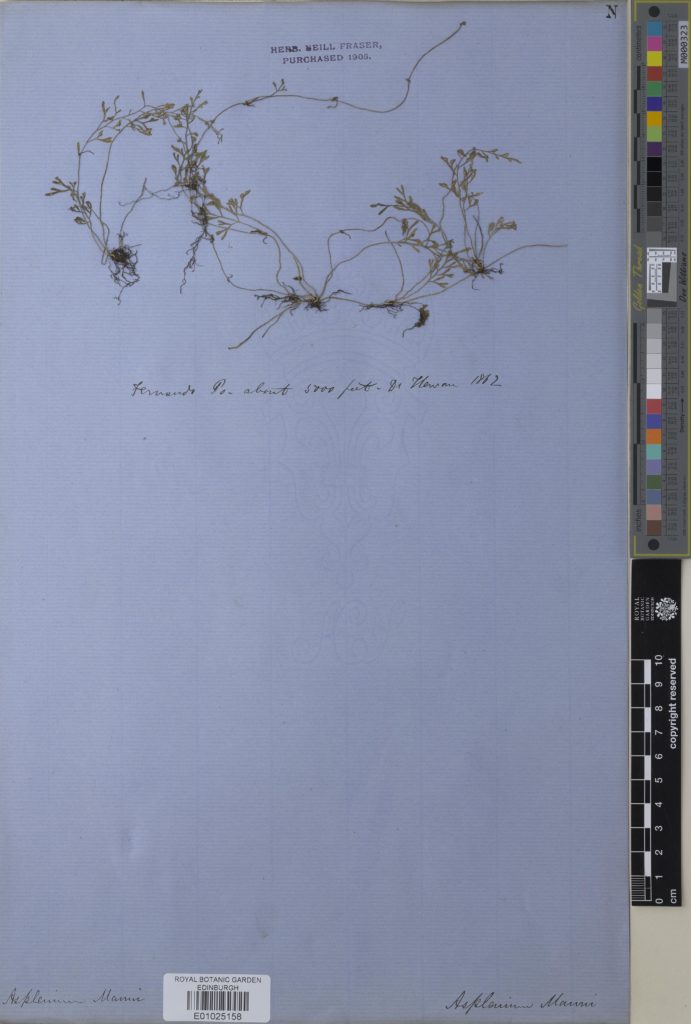

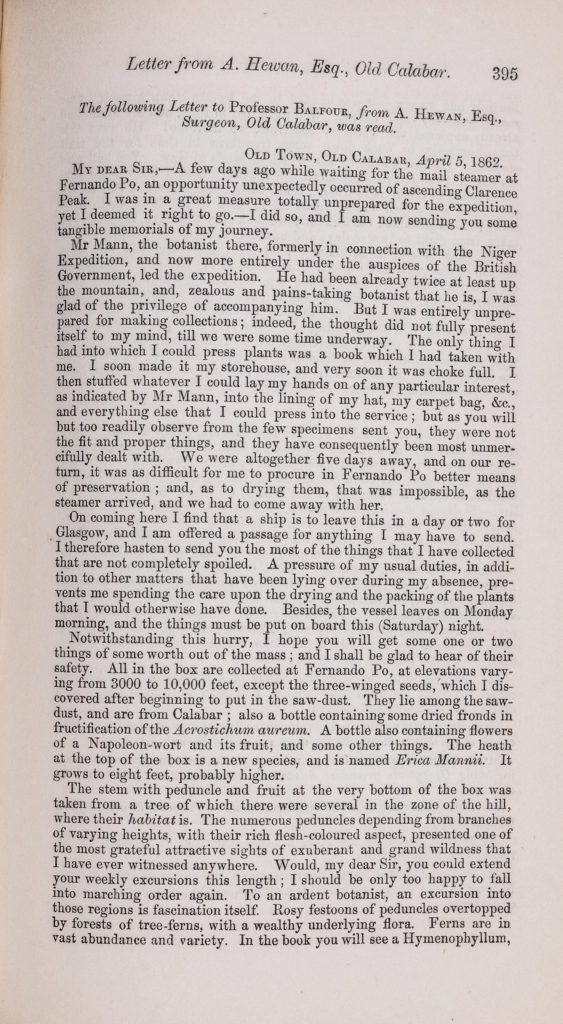

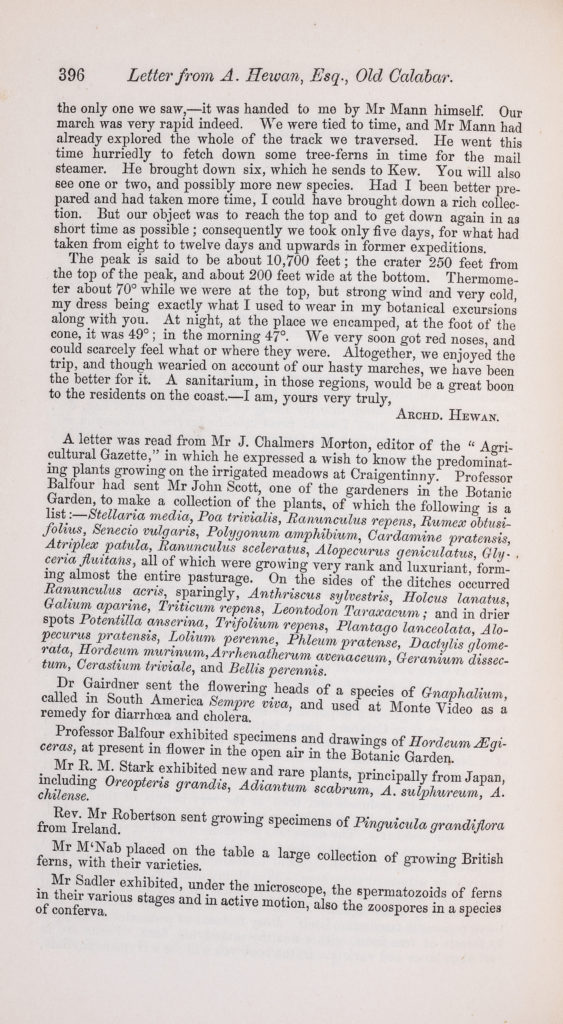

As a member of the Botanical Society of Edinburgh, Hewan was passionate about the plant world. A letter in our archives addressed to Professor Balfour tells of Hewan’s expedition with botanist Gustav Mann to Fernando Po, what is now the island of Bioko in Equatorial Guinea. There, he seized the chance to collect plants, writing: “The only thing I had into which to press plants was a book which I had taken with me. I soon made it my storehouse and very soon it was choke full. I then stuffed whatever I could lay my hands on of any particular interest into the lining of my hat, my carpet bag …”.

A full transcript of Dr Hewan’s letter appears at the end of this story*.

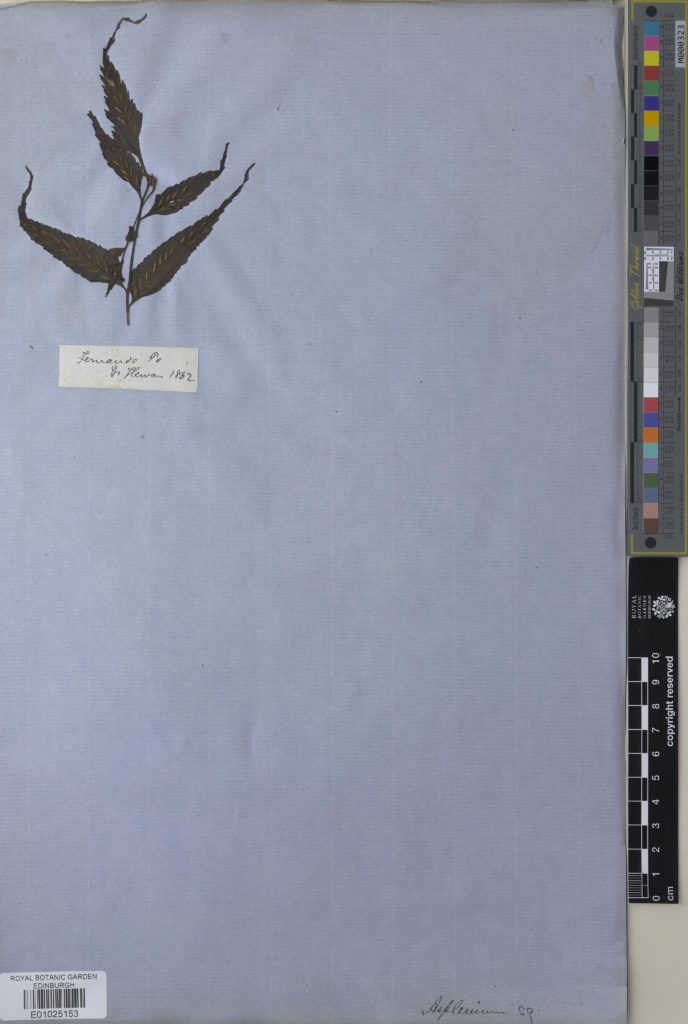

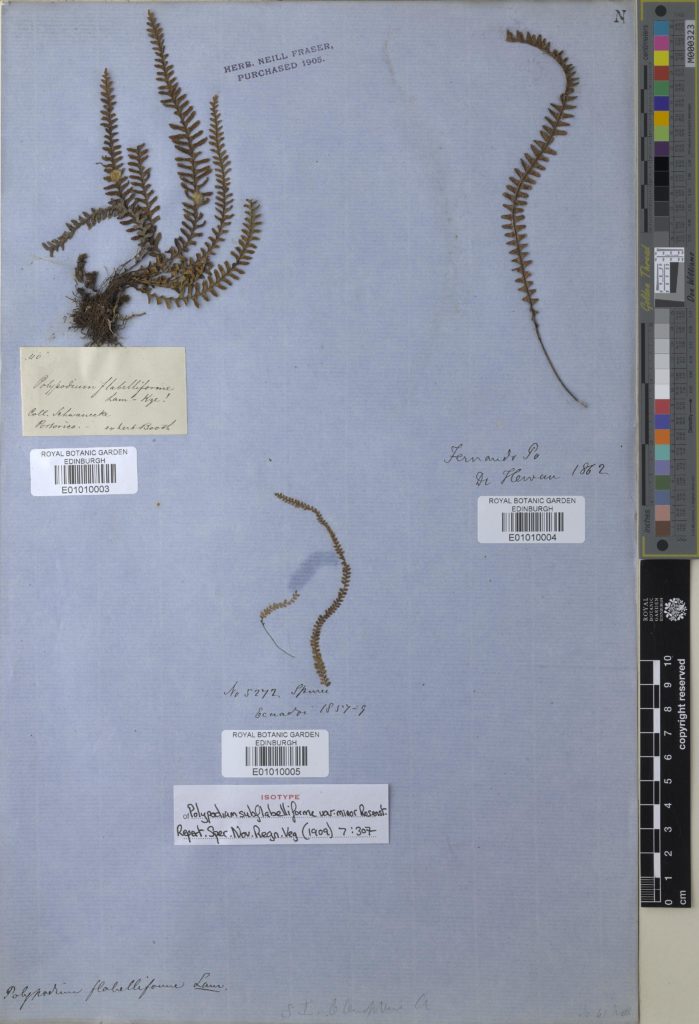

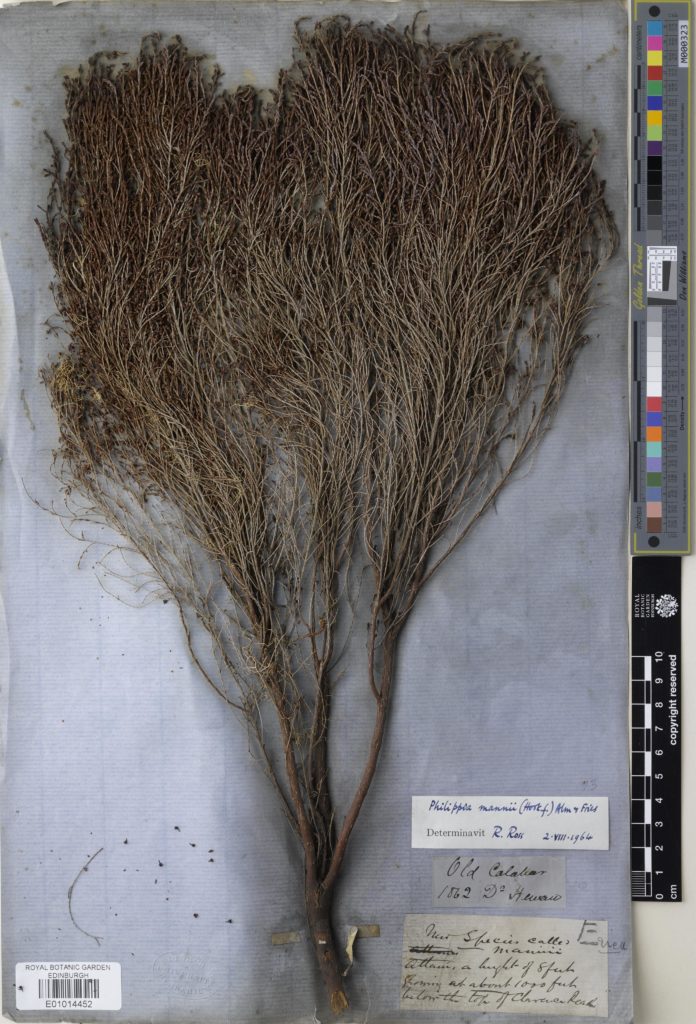

The results of Hewan’s efforts are recorded and held in our herbarium where we have 13 known specimens of the plants he collected.

Dr David Harris, herbarium curator and deputy director of science, says: “Dr Hewan was one of many medical doctors trained in Edinburgh who in the 19th Century travelled to practice in other parts of the world and sent information and herbarium specimens of plants back to their former teachers in Edinburgh. These specimens were one of the main ways that the scientific community was able to have a global understanding of plants. On reading Dr Hewan’s letter, I can feel the enthusiasm of a botanist sharing his findings with a colleague.”

*****

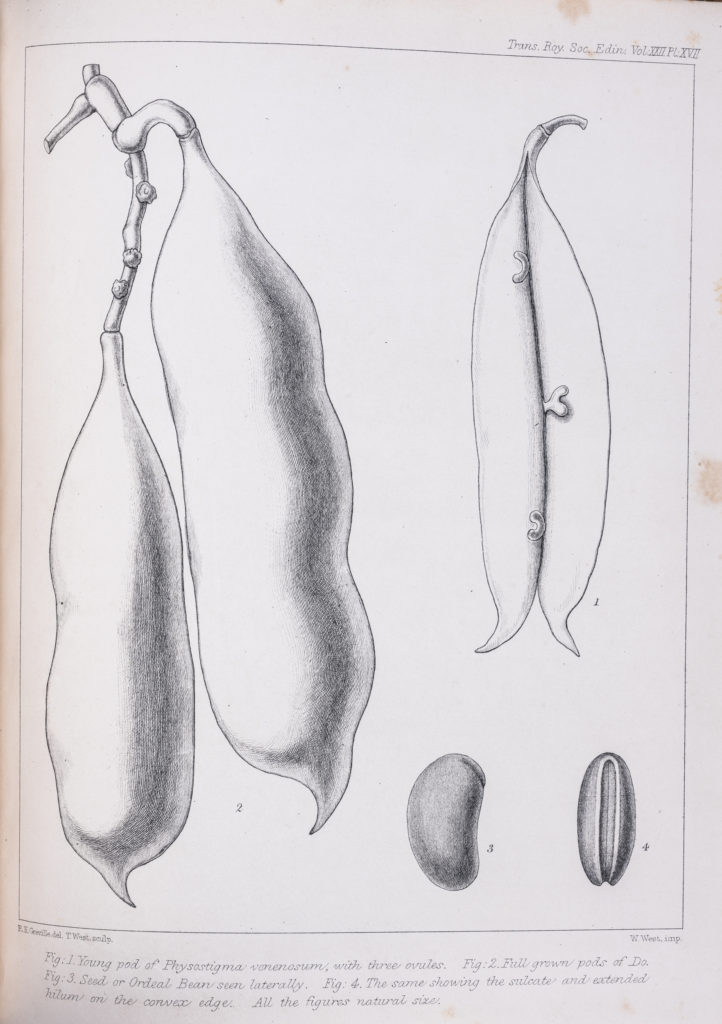

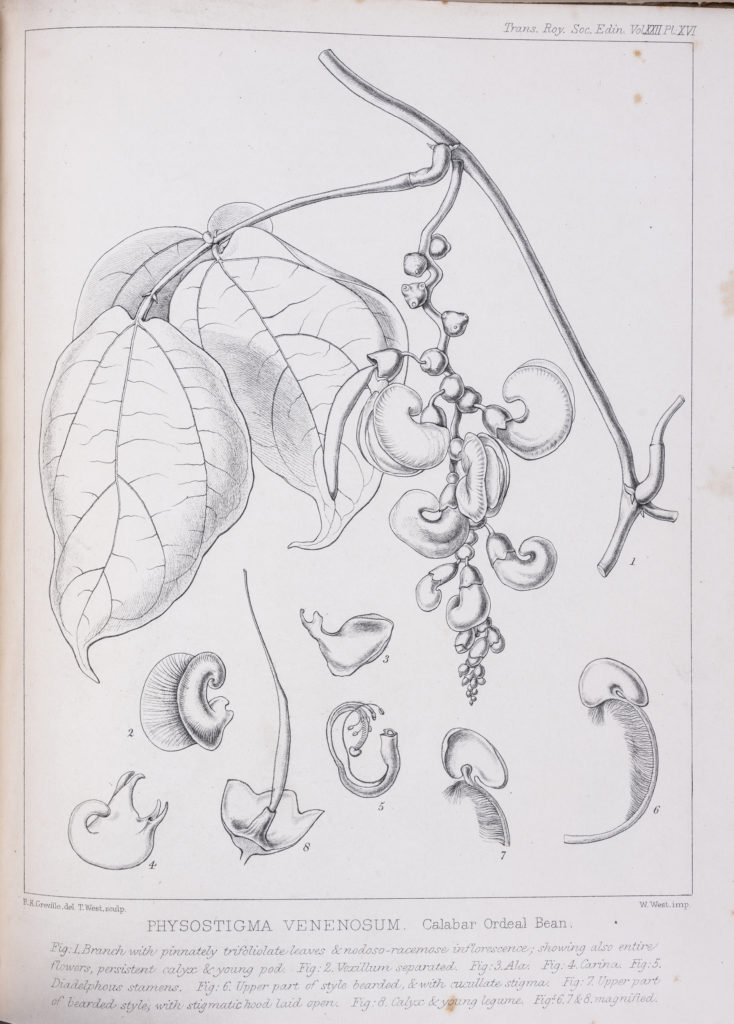

In a second letter in our archives Hewan references a consignment of the Calabar bean, Physostigma venenosum, on its way to Professor Balfour. This highly poisonous plant seed was regularly used by the Efik people in ‘trials by ordeal’, often ground and made into a drink for the accused. Survival from ingestion indicated innocence, death indicated guilt. Missionaries, keen to identify the poison and develop an antidote, sent seeds to Scotland. Balfour was first to describe the plant to science and even tried, unsuccessfully, to cultivate it in the Garden’s Glasshouses. His early taxonomic work paved the way for future medical discoveries into alkaloids and the drug physostigmine.

*****

Dr Hewan finally left west Africa in 1864 because of ill health, returning to Edinburgh and to the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh as a student. His medical achievements at this time included the presentation of a paper on pregnancy and childbearing among the Efik, to the Obstetrical Society. He delivered his presentation at the request of the eminent Professor James Young Simpson**, with whom he was personally acquainted. In the same year, he received a licentiate from the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh.

In 1866 Dr Hewan graduated from the University of Edinburgh with a Doctor of Medicine degree with a thesis ‘On Malarial Poisoning’ for which he was commended. He then moved to London where he spent his later years with his wife and children and continued his medical practice. He subsequently published many medical papers including one on smallpox in The Lancet (1877). He sadly died in 1883 at the age of 51.

Dr Hewan’s life was not without struggles and he was not always treated as an equal. For example, his appointment as a Jamaican graduate to the Scottish mission in Calabar took many months to process while a fellow white missionary was accepted within days. In 1865, he successfully brought charges against his senior white missionary for vindictive and unreasonable behaviour.

We are delighted to pay tribute to a brave and compassionate man, remembered through this story and through our archives. Dr Hewan’s plant specimens have now been digitised and high-quality scans can be downloaded from the RBGE online catalogue so that the new generations of biodiversity scientists across the world have access to this data.

Further letters and artefacts from Hewan’s expeditions are held at the National Library of Scotland, the National Museum of Scotland and the Natural History Museum, London.

*****

*Full transcript of Dr Hewan’s letter, dated 1862:

*****

**Sir James Young Simpson was a Scottish obstetrician, who introduced the use of anaesthesia in childbirth. The Simpson Memorial Maternity Pavilion in Edinburgh is named in his honour.

*****

Researched by Graham Hardy, RBGE’s Serials Librarian and Margaret Dunn Communications Volunteer, and written by Paula Bushell Head of Marketing and Communication.

Special thanks to: Beth M. Robertson, Professor David Killingray and Lisa Williams Founder of the Edinburgh Caribbean Association and Honorary Fellow, History, Archaeology and Classics, the University of Edinburgh. Zachary Kingdon Senior Curator of African Collections at National Museum of Scotland, Alison Metcalfe Archivist at National Library of Scotland and Danielle Spittle Archives and Library Assistant at the University of Edinburgh. Dr Jacqueline Cahif at The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh and Estela Dukan Assistant Librarian at the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. At RBGE, Leonie Paterson Archivist and Jamie Lawson Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Manager.

Sources:

Beth. M. Roberston, ‘Edward Stirling: Embodiment and Beneficiary of Slave-Ownership’, Australian Journal of Biography and History, No.6, 2022.

David Killingray, ‘Black Atlantic Missionary Movement and Africa 1780s-1920s, Journal of Religion in Africa, 33, 1(2003), 3-31.

Bela Vassady Jr, ‘The Role of the Black West Indian Missionary in West Africa 1840-1890. Temple University PhD 1972.

Michael Radcliffe Lee, Plants: Healers and Killers, Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh 2015.