In November 2024, a one-month project funded by the Sibbald Trust aimed to create a top-level finding list for the archives of the late RBGE botanist, Jimmy Ratter. The project sought to provide an overview of the contents of the collection and identify items of particular interest that should be prioritised for more detailed cataloguing. It is hoped that the findings produced by the project will provide a basis for future interdisciplinary research within the collection, alongside further collaborations with Brazilian partners.

Written by Rose Kent.

When Jimmy Ratter was young, he was fascinated by two things: cars and fish. He could remember the first fish he ever caught when he was about five years old – it was a small roach from the pond at Calderstones Park in Liverpool.

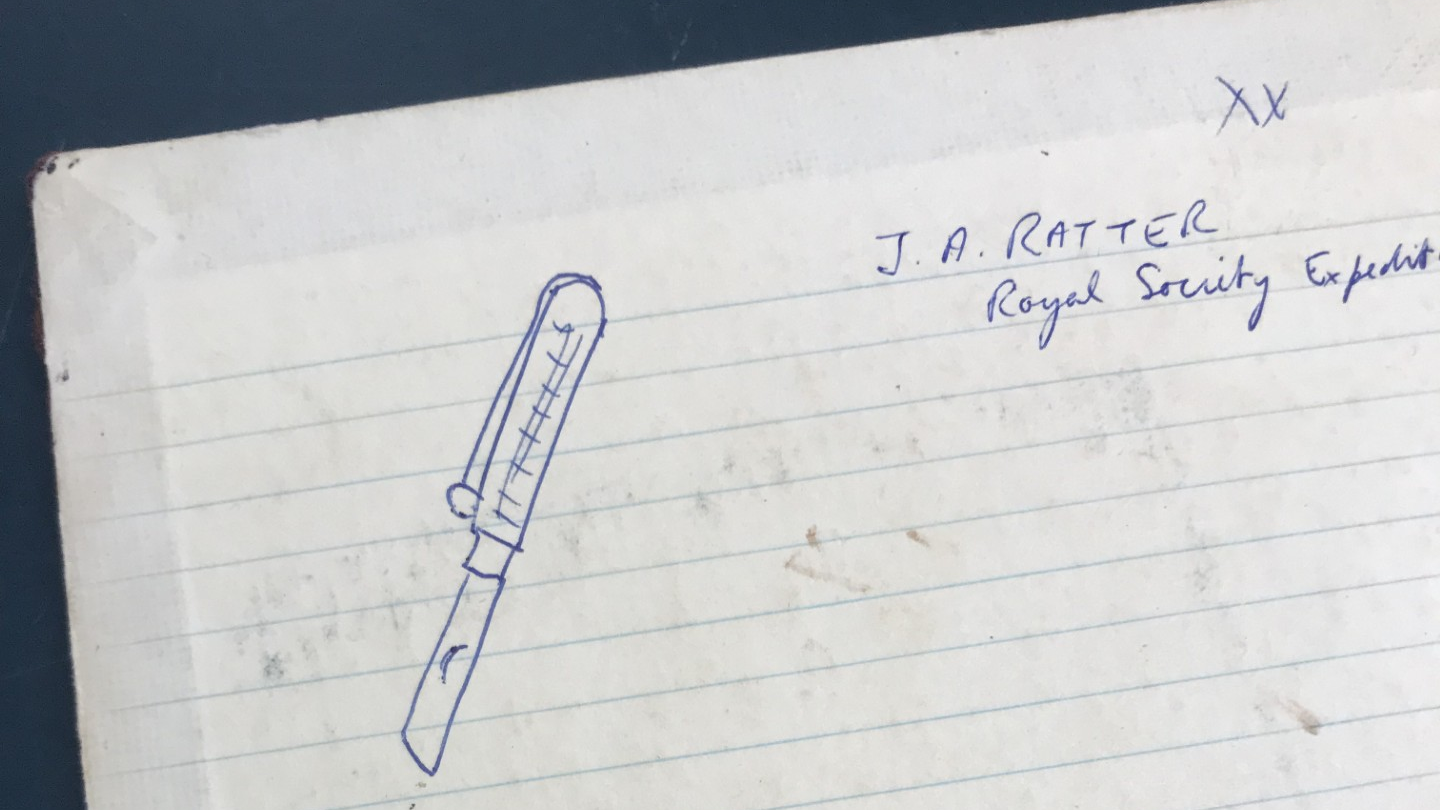

Jimmy also claimed that at only 18 months old he was able to name the different makes of motor vehicles. As he put it, “my uncle was fascinated by motor vehicles and used to test me… I had an interest in taxonomy, clearly. It was the resemblance of vehicles, makes of vehicles and the relationship of vehicles if they’d come from the same maker that I obviously picked. I could only just talk, and my uncle saw a car which was parked in Blackhall. He took me down to see this car and asked me what it was. And I had great difficulty, I can just about remember this… inspecting it and looking at it… I said I wasn’t sure but I thought it was a very old Renault – and it WAS a very old Renault. Which in a way wasn’t such a difficult recognition as one might possibly think…”

In Jimmy’s archives at the RBGE, cars and fish are gently threaded through the collection. They surface every now and then and recall these stories of Jimmy’s earliest infatuations and taxonomic intuitions. It probably shouldn’t have been a surprise to open up one of more than 60 boxes that make up the collection, and find, amongst vegetation surveys and letters doodled with various trucks and vehicles, a pair of catfish stingers…

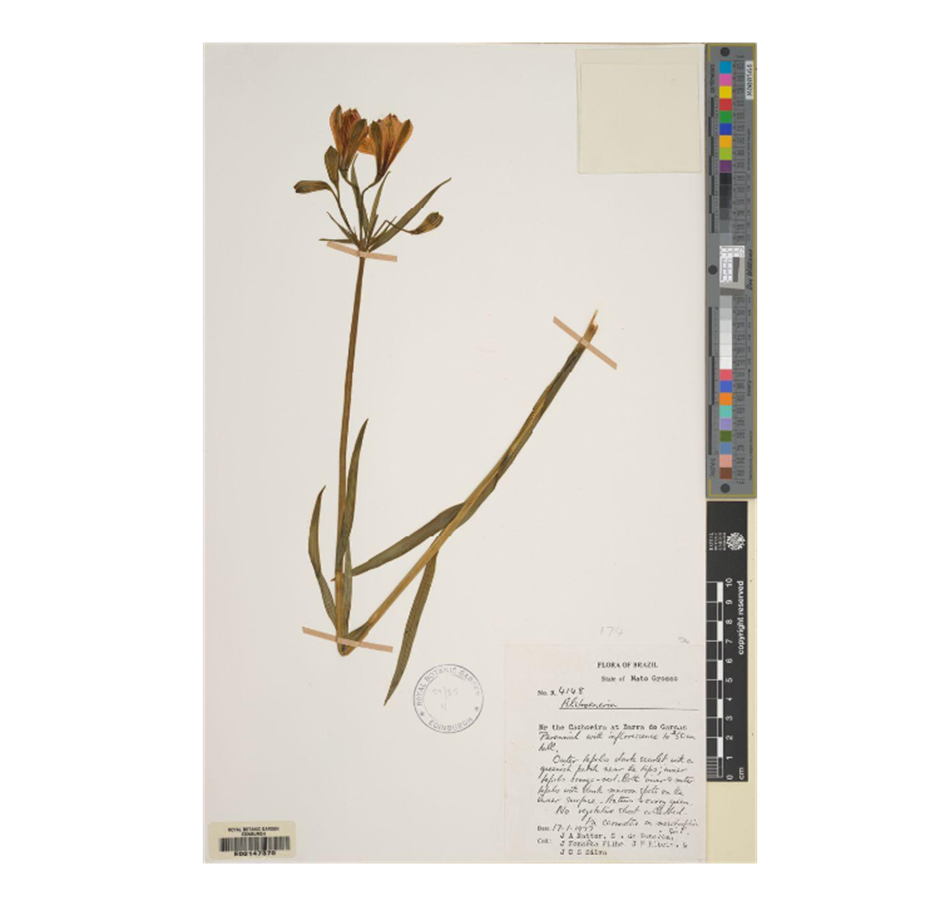

Jimmy was an exceptional botanist who devoted his career to the understanding and protection of the cerrado, a vast tropical savanna region in Brazil. Undoubtedly, his archives at the RBGE represent an invaluable scientific resource. But the collection also captures the curious idiosyncrasies of a personal archive. It encompasses the perplexities and the oddities, such as the fish and the motor cars, that complicate and animate the archives, and the stories it tells.

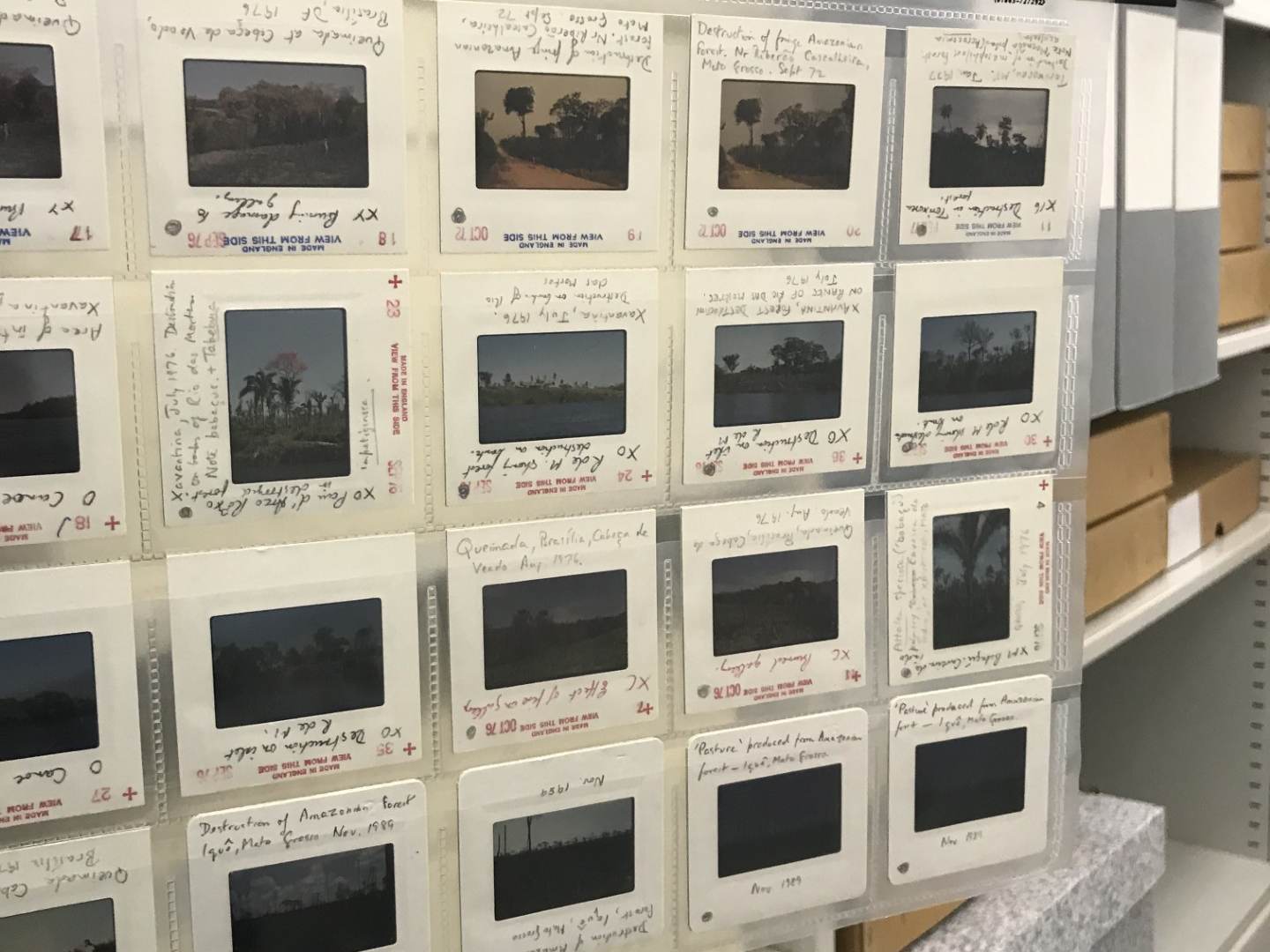

And so, the Jimmy Ratter Archives are delightfully haphazard. Field surveys, photographic slides, and written depictions of the Brazilian flora he came to know so well are found alongside Portuguese comic books (annotated by Jimmy as he learned the language), handwritten lecture notes and talks, and multitudes of correspondence between students, colleagues, and friends. There are sketches of plants, postage stamps from Brazil and beyond, annotated PhD manuscripts, plant collection books, drafts of scientific papers, and a curious document entitled, “Disjointed thoughts on biodiversity, or the ramblings of St. James the Divine.”

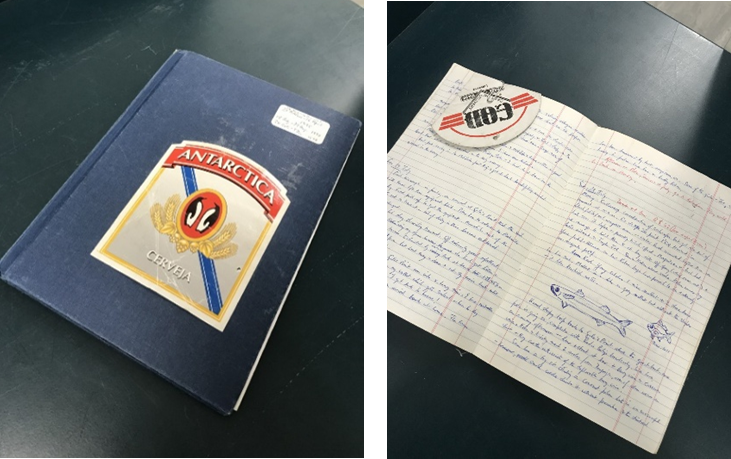

There are also Jimmy’s numerous field diaries, that detail the various people he met and worked alongside in the sertão, the so-called “backwoods” of Brazil. Small fragments of plant material line the seams of these diaries as Jimmy chronicles the cerrado – its plants and its people – through detailed accounts of the landscapes he worked in. Alongside daily accounts of various close scrapes and misadventures (there is more than one that involves a jaguar) are also poems, scribbles of Portuguese words to remember, sketches (of plants, cars, and fish, of course), and the signed names of his co-collectors. Each field diary is embellished with the reds and golds and blues of Brazilian beer bottle labels.

Through his archive, the sociability of Jimmy’s work in Brazil is clear. Represented in the collection is a sense of the collaborations, interactions, and friendships that exist between his publications and pressed plant specimens. People and plants are deeply and diversely intertwined in Jimmy’s documentation of the cerrado: threaded through his letters, photographs, and field journals is a personal and botanical testament to these unique landscapes and the people who lived and worked there.

The decades are traced in Jimmy’s archives through the sifts of letters to FAX messages to emails, or as the floppy discs become slightly less “floppy” and then disappear entirely. During these decades, the landscapes of the cerrado changed enormously due to agricultural intensification. From his letters and written accounts to his species lists and transect notes, Jimmy’s archives offer a distinct and personal social history of particular people and places in Brazil during this time of immense change. The collection becomes, in some places, an elegy to these past landscapes that have since ceased to exist.

The collection had previously been removed from Jimmy’s office in 2020 during the covid pandemic. Items were wrapped in bin-bags, frozen, and safely stored in the library basement stack. When items were removed from Jimmy’s office, they were labelled as to which drawer, cabinet, or shelf they had been found in. We have since tried to maintain, to a certain extent, a sense in the collection of how Jimmy had kept and ordered his things. There is a charisma to the collection – and in preserving it, we have tried not just to archive its contents, but to capture something of the space it once filled.

Jimmy’s archive exists not only as a record of his work but a reflection of the relationships, landscapes, and histories that shaped it. It stands as both a scientific resource and a deeply personal record that can offer invaluable insights for future interdisciplinary and collaborative research.