By Madeleine E. Dugan

My name is Madeleine Dugan and I am an Art History Mlitt student. As part of my studies at the University of Glasgow, I completed a work placement in the Library at the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. During my cataloguing project, I became interested in the works of Elizabeth Haig (1871–1954), whose mysterious yet prolific output of botanic studies intrigued me.

Elizabeth Haig was born in London, England, as the sixth child of Jane Thompson (circa 1835–1877) and James Richard Haig (1831–1896) of Blairhill and Highfield. She grew up in Muckhart, Perthshire, Scotland but later returned to England by 1901.[i] Via her great-great grandfather, John Haig (1720-1773) and great-great grandmother, Margaret Stein (Dates unknown), Elizabeth Haig is distantly related to the Earl Douglas Haig (1861-1928) and his brother William Henry Haig (1841-1884), the whisky distiller who resided at Broomfield.[ii]

Elizabeth Haig’s collection consists of 662 original botanical illustrations, a majority of which depict Mediterranean flora. Haig presented her works to RBGE in 1938, but, aside from her annotations on the verso of her works, there is no accompanying written material within the collection. Haig was acknowledged within the Dictionary of British & Irish Botanists and Horticulturists, as well as the Dictionary of British Flower Painters volume 1, however, there is scant information written about her, aside from the notation of her works residing within RBGE’s collection. This is not uncommon for women artists prior to the Feminist movement of the nineteen-sixties and seventies, and especially for women working prior to the World Wars. Women in the Victorian and Edwardian eras were expected to be modest and unambitious in their pursuits, and as such, it was improper for them to boastfully exhibit their accomplishments with their names in newspapers. This makes it fairly difficult to track down relevant information about these individuals, especially in regard to women like Elizabeth Haig, who were creating botanical illustrations to bolster their passionate study of botany, and not for the purpose of publication.

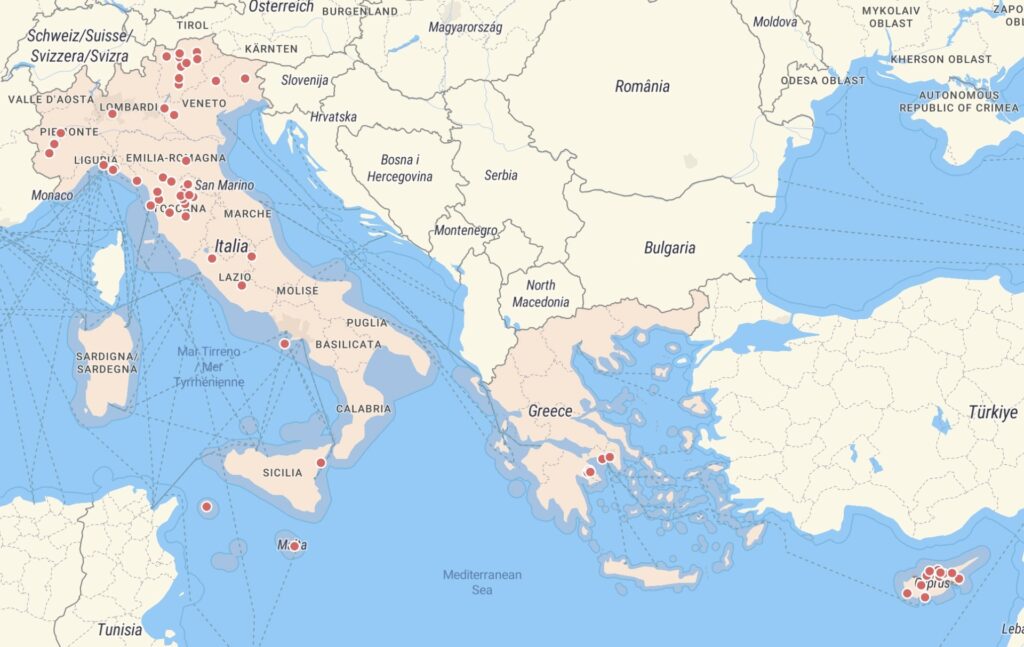

Haig’s works mostly depict plant species that she observed on her travels throughout the Mediterranean, specifically within Italy, Cyprus, Greece, and Malta. Her annotations keep track of where she ventured, during which months she travelled, and where she found specific plants. These locations include meadows, roadsides, the Boboli Gardens, ‘behind [a] Roman theatre,’ or in ‘parks of grand ducal villas,’ among others. On the backs of her paintings she often notes which months certain species of flora are likely to grow, and where they are most plentiful.

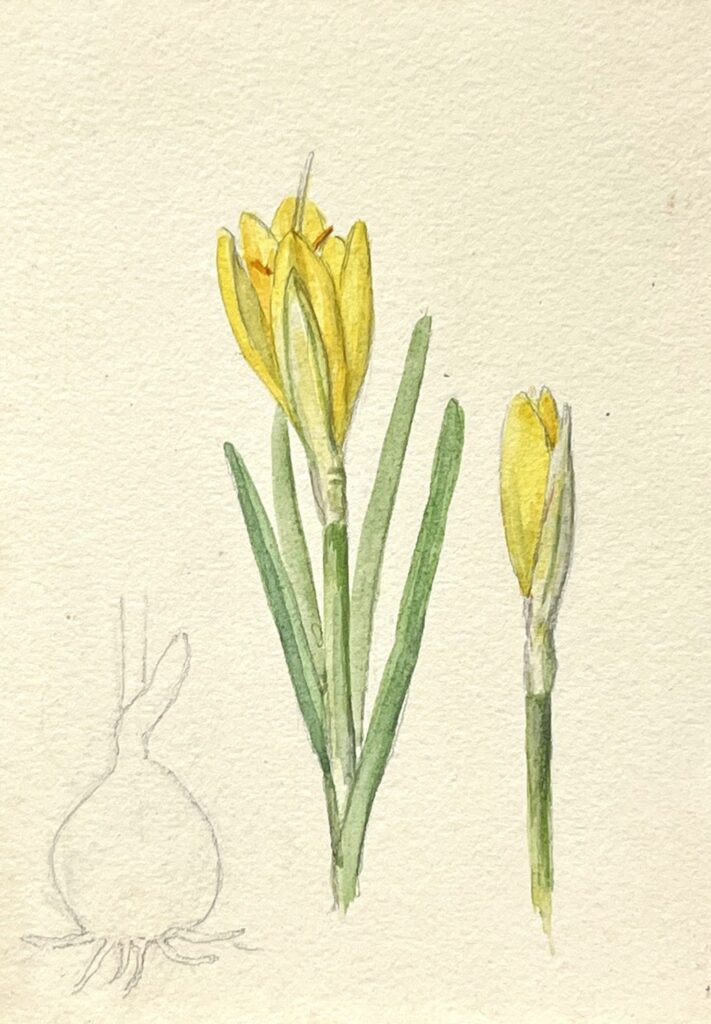

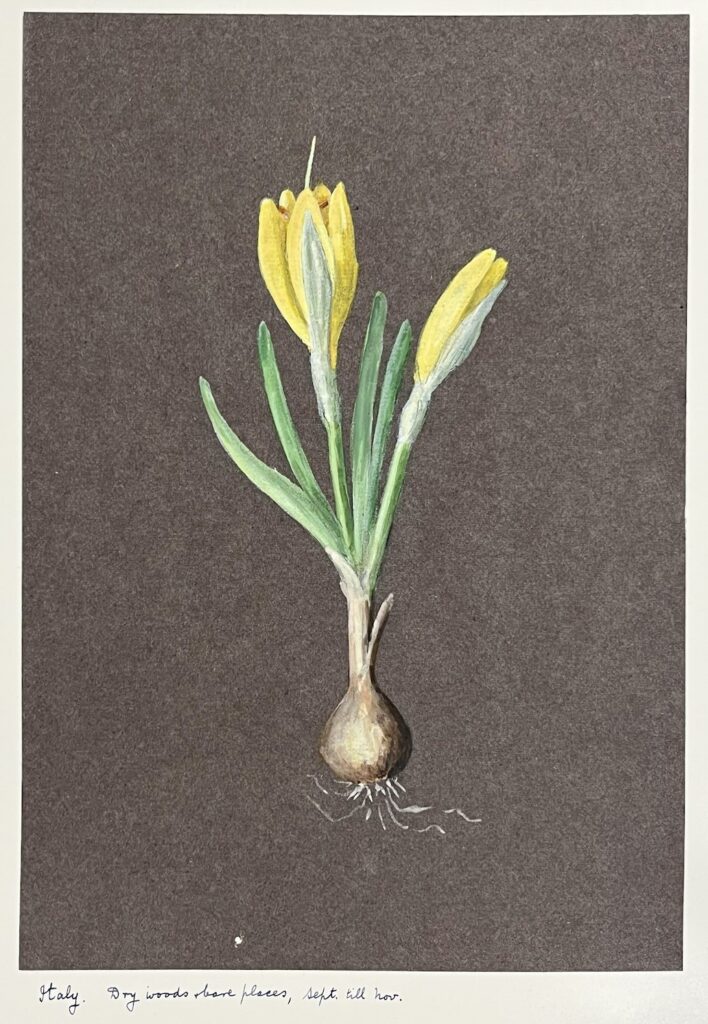

While Haig did not leave us many records of her thoughts, aside from the notations on the verso of her works, a fair amount of insight can be gained from the illustrations themselves. The works that Haig completed in the field are identifiable through their airy quality, with light paint application on top of pencil sketches, often hosting additional studies on the reverse side. Many of these field sketches remain unfinished and display slight paint splatters across the surface, perhaps a result of windy conditions en plein air. The works on which Haig spent a prolonged time painting at home are often more detailed and scientifically accurate, illustrated as botanical studies with enlarged views of flowers and root-systems. Though a majority of Haig’s works are small-scale field-sketches, it is clear that when she was interested in a particular plant, she paid significantly more attention to it. This is indicated by her choice to revisit particular watercolour sketches, which she later turned into gouache paintings on black paper.

Left – Sternbergia lutea, Circa 1902–1938, Watercolour and pencil on paper, RBGE; Right – Sternbergia lutea Ker-Gawl., Circa 1902–1938, Gouache and pencil on paper, RBGE.

Haig’s interest in certain flora can also be observed through the scale in some of her works, such as in her painting Mandragora officinarum L.. While this work has an element of the impressionistic paint-application that is seen in a majority of her field sketches, the piece is significantly larger in scale and it is more dynamic in composition. The painting also includes a descriptive note on the verso, which expresses her fascination with this particular species: ‘There seems to be no folk-lore connected with it in Cyprus, though it is still valued in the Western Mediterranean, the dried root being worn as an amulet against barrenness in women.’

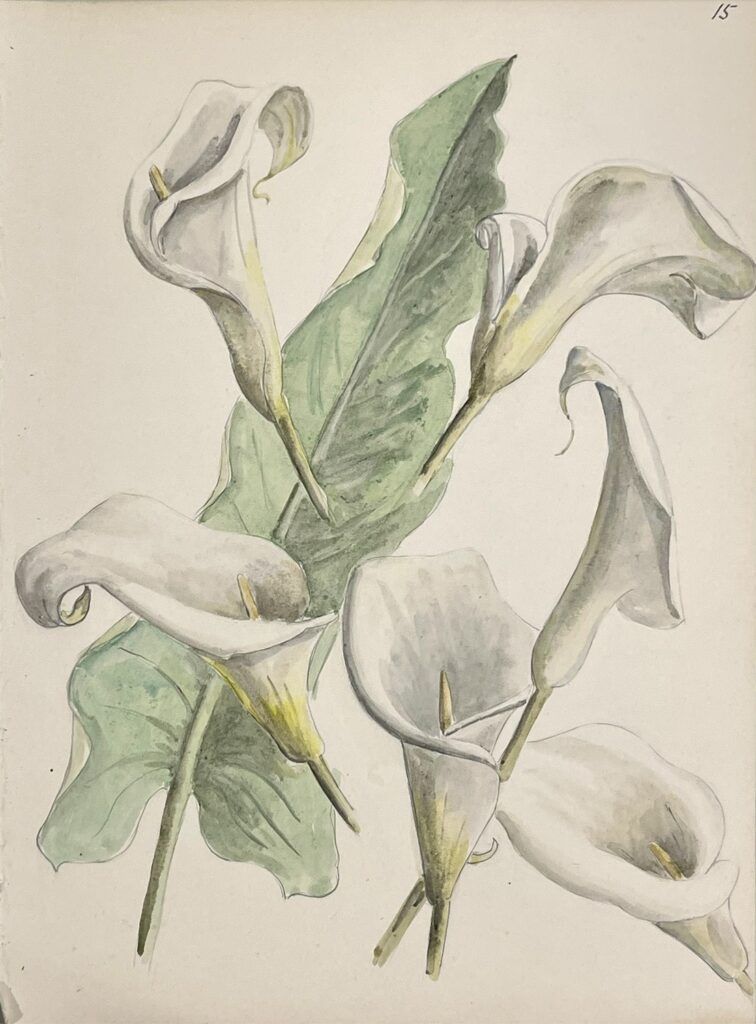

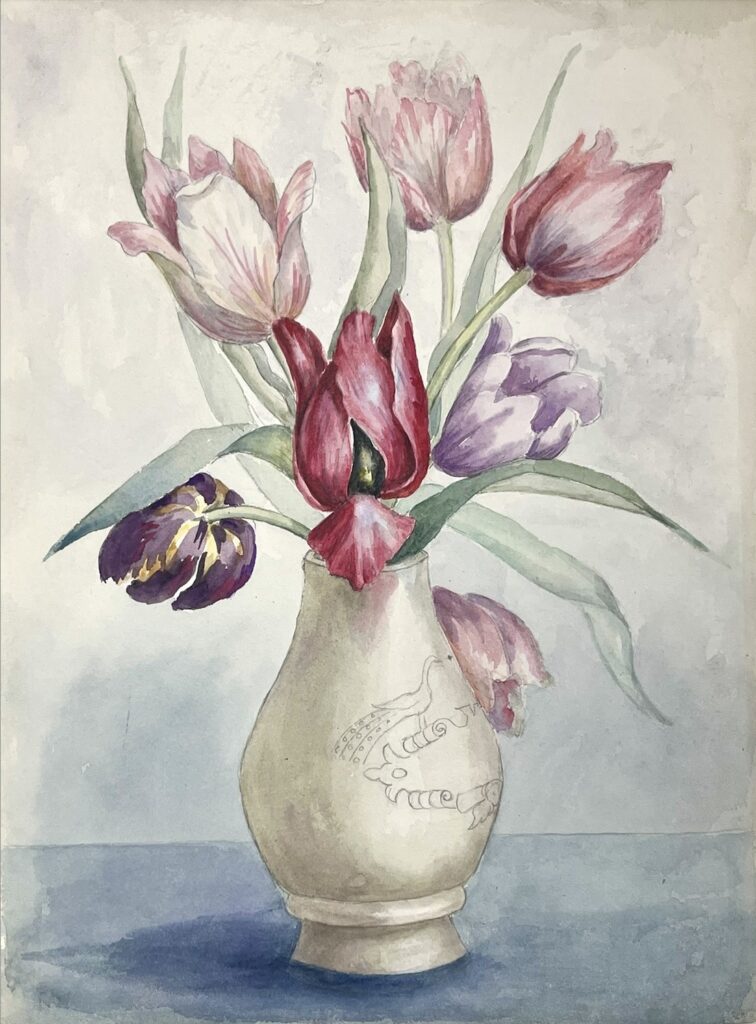

Haig also created a number of still lifes, done in watercolour, gouache, and even oil. Her more traditional studies of houseplants and bouquets are likely a result of botanic illustration classes, as a grouping of works are labelled with numbers in their upper right corners, all on the same size and type of paper. Haig likely exhibited some of her more refined paintings during her lifetime, which is implied by their scale, detail, and her prominent signature ‘E. Haig’ proudly inscribed on the front of these works.

Left – Untitled [Calla Lilies], Circa 1902–1938, Watercolour and pencil on paper, RBGE; Right – Untitled [Pink and purple tulips in porcelain vase], Circa 1902–1938, Watercolour and pencil on paper, RBGE.

Along with her illustrations, Haig was also clearly collecting plant specimens during her travels. This can be understood from a certificate of thanks from the British Museum (Natural History) posted on 2 August 1933, signed by the Director, Charles Tate Regan. This letter thanks Haig for her donation of a parcel of plants, which included twenty-six specimens of flowering plants and one fern from the Mediterranean.[iii] She received a follow-up letter on 10 September 1933, from Alfred James Wilmott, the Deputy Keeper of Botany for the British Museum (Natural History) from 1931 to 1950, verifying the types of species that she had included within the parcel.[iv] Her specimens reside in the collection of the Natural History Museum and include species such as Mandragora officinarum L., Orchis collina (Banks & Sol. ex Russell), and Hyoscyamus aureus L., all collected from Kyrenia, Cyprus, as well as Hyoscyamus aureus L. from Athens, Greece.[v] Her specimens are also cited within Robert Desmond Miekle’s Flora of Cyprus, Volume 1, produced by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew in 1977.[vi]

Given her interests in painting and botany, it is likely that she is the same Elizabeth Haig who authored The Floral Symbolism of the Great Masters in 1913. As was common for work published by women during this time, the book was regarded as an amateur endeavour by a lady writer. Haig describes her intent for writing the work: ‘This little book has been written for the pleasure of those amateurs who are more interested in the idea which inspires a picture than in the picture’s workmanship.’[vii] Despite this modest statement, Haig’s book displays her strong understanding of the art historical canon of Christian symbolism, and she provides persuasive visual analysis to back up her claims. The Floral Symbolism of the Great Masters was the topic of numerous newspaper and journal reviews in 1913. One critic described it as ‘a most useful, suggestive, and interesting manual of the art, albeit it is of a character more devotional than strictly scientific and by no means exhaustive.’[viii] Another review states that the “book shows accurate observation of plant-form, diligent research, and an independent taste for a certain type of poetic representation, but it is written in an assertive and unconvincing manner.”[ix] Despite the dismissal of her writing by her male contemporaries, Haig’s book has been cited as a relevant source in publications such as The Language of Flowers by Beverly Seaton and Early Netherlandish Painting by the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C, among others, even over one hundred years after it was originally published.

Despite going through all 662 of Haig’s artworks, there was not a single year written on any piece of her art. The works were clearly created throughout a range of years, as her skills appear to improve throughout time with her continued practice. It is possible that her paintings were originally done in sketch pads that were dated, and then were later torn out. This can be surmised from the adhesive residue on edges of papers with the same measurements, indicating having once been adhered to a sketchpad. Haig presented her works to RBGE in collections of folders, which she had organised and labelled by plant families. Presumably, as a respectable lady, she would not have been out traveling until her twenties, which would have been after 1890. There is a census record that does mention Haig living with her older brother in London in 1901, after which she may have embarked on her travels. The collection was presented to RBGE in 1938, meaning all works must have been created at least prior to her donation. This widely dates the artwork in the Library’s collection to circa 1902 until 1938.

Haig died on 25 March 1954 in Via de’ Bardi, Florence, Italy.[x] Her last known residence was comfortably situated along the Arno River, and just a short ten-minute walk to the Boboli Gardens, where she often sketched the flowers. Given her lifelong passion for painting and her closeness to these gardens, she likely continued to produce work up until her death. She is laid to rest in the common ossuary at the Cimitero Evangelico agli Allori, Florence, her marker reading “Elisabetta Haig.”

Elizabeth Haig’s collection is now catalogued on the RBGE Library Catalogue and a detailed spreadsheet record of her individual works is available upon request.

[i] Family Search, “Elizabeth Haig,” Accessed March 31, 2025, https://ancestors.familysearch.org/en/LTRG-M5F/elizabeth-haig-1871-1954.

[ii] Despite the distant relation, it is possible that Elizabeth Haig may have known and interacted with these other Haigs, as she was also living in London at the same time as the Earl and his family. It is also interesting to note that Ruth Haig de Preé (1873-1944) and Rachael Winifred Haig (1880-1941) subscribed to the Royal Caledonian Horticultural Society and the Scottish Horticultural Association.

[iii] [Charles Tate Regan to Elizabeth Haig, August 2, 1933, Elizabeth Haig Collection, Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh Library.

[iv] Alfred James Wilmott to Elizabeth Haig, September 10, 1933, Elizabeth Haig Collection, Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh Library.

[v] Natural History Museum, Specimens (from Collection specimens), [Data set resource], Natural History Museum (2014), https://data.nhm.ac.uk/dataset/collection-specimens/resource/05ff2255-c38a-40c9-b657-4ccb55ab2feb.

[vi] Robert Desmond Meikle, Flora of Cyprus 1 (Kew: Bentham-Moxon Trust, 1977).

[vii] Elizabeth Haig, The Floral Symbolism of the Great Masters (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co, 1913): iii, https://archive.org/details/floralsymbolismo00haiguoft/page/n7/mode/2up.

[viii] Kegan Paul, “New Books: Floral Symbolism,” The Evening Post, May 29, 1913, https://www.newspapers.com/image/932091603/?match=1&terms=Elizabeth%20Haig.

[ix] T.L.F., “Reviews,” The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 24, no. 128 (1913): 116, http://www.jstor.org/stable/859540.

[x] “Deaths,” The Daily Telegraph, April 1, 1954, https://www.newspapers.com/image/828240931/?match=1&terms=Elizabeth%20Haig.