The NRF (Nature Restoration Fund) Scottish Plant Recovery Project at RBGE aims to restore genetically diverse populations of our endangered Scottish native plants around the country. Whilst rewarding, the project does not come without obstacles, whether it be harsh weather, tight deadlines, or horticultural challenges.

Polygonatum verticillatum or Whorled Solomon’s Seal is one of the species focused on in the project that demonstrates the horticultural issues we can run into whilst cultivating endangered plants ex-situ (outside of their natural habitat). A delicate cream whorled flower that emerges in May, P. verticillatum is a plant that produces shoots from a thick rhizome from where it receives its common name (the rhizome is said to look scarified in a manner that resembles King Solomon’s Seal). Due to factors such as climate change, land management and overgrazing, this species has been pushed to the edge of its habitat niche and now only exists in a few inaccessible woodland gorges in Scotland.

Work began cultivating this plant in 2023, and the collection went on to successfully shoot and produce flowers. However, in early June that year, the plants severely mosaiced on the leaves, yellowed in colour and died back, which worried the team as no seed was produced. This dieback event repeated in 2024, again generating no seed and raising the concerns of the team. Our first thoughts were that this mass dieback was the result of a plant virus, and so plant samples were sent to SASA (Science & Advice for Scottish Agriculture) who could unfortunately only declare the plants free of specific viruses they tested for. However, the team remained concerned that a different and untested virus might be responsible for the poor health of the collection.

There is a hefty risk to translocating plants with viral material. With only 8 recorded populations of P. verticillatum in Scotland, the introduction of a virus into our wild populations could risk reducing already very low numbers or potentially even cause extinction of this species in Scotland. It is the responsibility of the NRF team to ensure that this plant material is safe for translocation into the wild. If we felt that the material had any chance of carrying a virus, our entire collection of P. verticillatum may have to be destroyed. Losing our collection of these endangered Scottish native plants would be devastating; however, it is crucial that we maintain high biosecurity levels for the sake of protecting this species, especially whilst its future is already so fragile.

Currently, the collection is looking healthy and producing seed with little signs of yellowing. Due to how well the plants are doing this year, we are now wondering whether the yellowing and dieback was actually the result of a virus, or whether it was cultural factors, such as root disturbance when initially divided.

Horticultural Trial

To investigate whether horticultural factors may have caused the dieback, the team is conducting a trial using the plant collection. In this mini experiment designed by Becca Drew Galloway (Project Lead Horticulturist), P. verticillatum from four different provenances have been evenly distributed into groups, each with a different controlled variable. These variables include shade levels, supplement feed, media composition, and wind exposure, accompanied by a control group which has no variables altered (all groups are subject to the same watering regime). Ideally this trial will expose if one of the P. verticillatum trial groups is performing better than the others, and if any variables have an influence on yellowing rate. ‘Success’ for the P. verticillatum plants was measured as a combination of a high number of shoots and low rate of yellowing.

In mid-May, I collected data from all plants in the trial, recording the different provenances and trial groups. The team suspected that the P. verticillatum plants in the shade would be more successful, due to them being in a similar environment to their natural habitat on woodland floor in dappled shade. Based on this reasoning, we suspected that the increased light levels were resulting in the lighter green colour and the higher rate of yellowing in the groups that did not have extra shade. It was also noted that the ‘Craighall’ provenance had a noticeably lower number of shoots per pot than the others.

DESCRIPTION OF TRIAL GROUPS

- Control: In 1:1 tree mix to leaf mould soil composition, in polytunnel (45% shade)

- Bluebell Garden: Planted out in the gardens, in dappled shade under trees

- Exposure*1: Windshield present

- Exposure*2: Windshield present and 60% shade

- Media*1: Open media of 2:1 tree mix and leaf mould

- Media*2: More open media of tree mix, leaf mould and hen grit

- Mycelium: Inoculated strain of mycelium taken from untreated soil sample from Den of Airlie (natural P. verticillatum population) introduced to the pots. Kept separately from other treatment groups to prevent spore transfer.

- Sulphite of Iron: Treatment applied every 3 weeks

- Magnesium: Treatment applied every 3 weeks

- 60% Shade: Under shade net with moderate shade

- 80% Shade: Under shade net with deep shade

- U02 Garden: Planted out in the gardens, light shade from surrounding vegetation

Results

For the trial, I used RStudio to analyse the data and assess the significance of any relationships or trends. The relationships between all variables (trial group, provenance, number of shoots, yellowing rate) were statistically tested and found to be significant through Chi squared tests and Fisher tests (p<0.05). This indicates that the trial groups are having a tangible effect on the success of the plants within each group, and that the level of plant success (both yellowing rate + number of shoots) is changing depending on what variable is being changed. It also indicates that provenance has a significant effect on yellowing rate (p<0.05).

| Table 1. Number of pots per trial. | |

|---|---|

| Number of pots per trial | |

| Bluebell Garden | 14 |

| Control | 56 |

| Exposure*1 | 56 |

| Exposure*2 | 56 |

| Magnesium | 56 |

| Media*1 | 56 |

| Media*2 | 55 |

| Mycelium | 35 |

| Shade*1 | 56 |

| Shade*2 | 56 |

| Sulphite of Iron | 56 |

| U02 Garden | 14 |

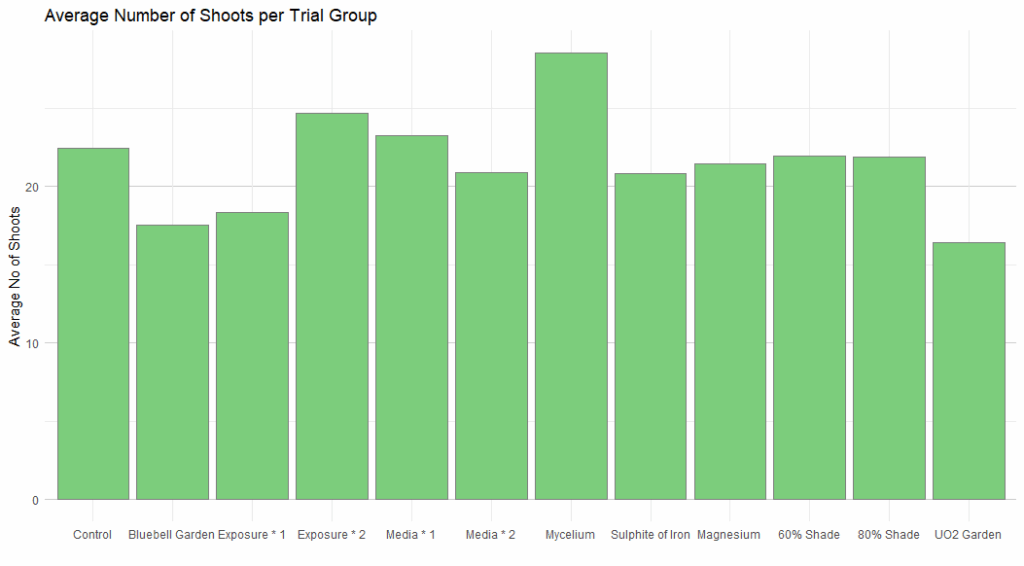

Figure 1 indicates that the Mycelium trial group has the highest number of shoots per pot at 28.5 shoots. Exposure*2 and Media*1 are the only other groups with a higher average plant shoot number per pot than the Control, with 24.6 and 23.2 shoots per pot respectively.

YELLOWING RATE

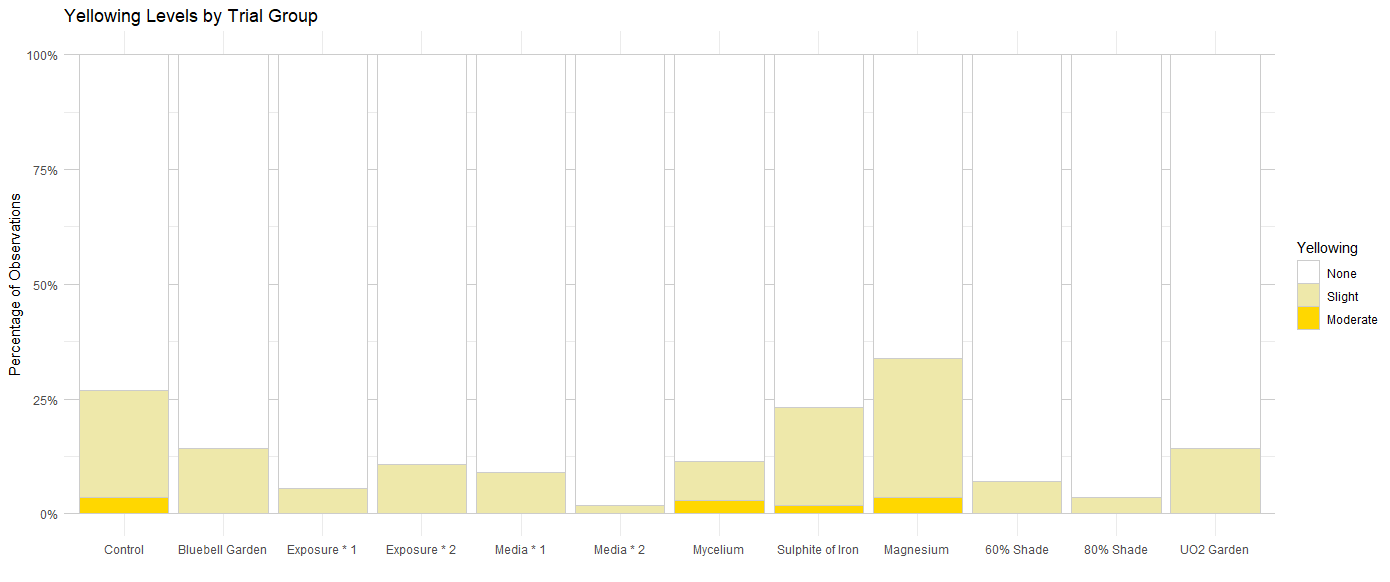

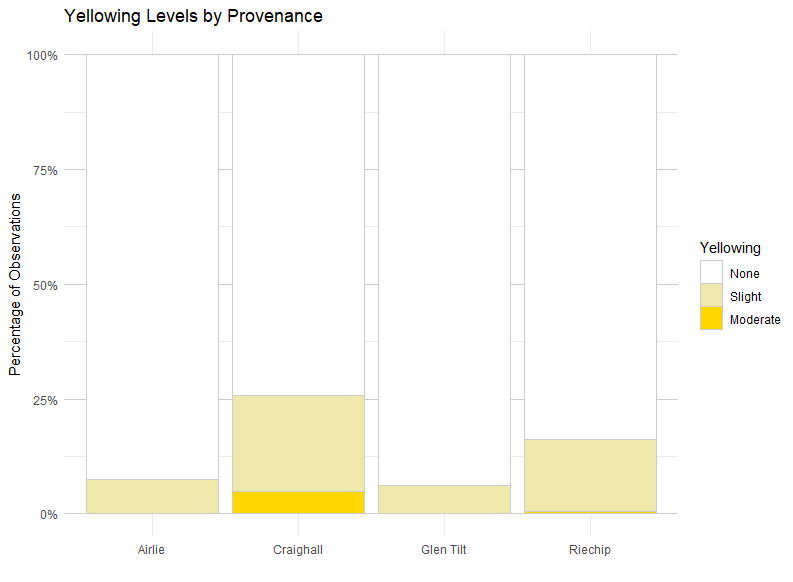

The provenance with the highest level of yellowing is Craighall. This is seen clearly in Figure 3 where most of the moderate yellowing in the collection can be attributed to this provenance, across all trial groups. Figure 2 displays that the Control group has a yellowing rate of approximately 25%. The only group with a higher yellowing rate is the Magnesium trial group, as approximately 34% of observations from this group display some form of yellowing.

Media*2 has the lowest rate of yellowing amongst all the trial groups at only 2% yellowing observed overall. Exposure*2 (80% shade) also has a very low rate of yellowing at 10%. Crucially, Figure 2 also displays that all groups which were additionally shaded demonstrated a lower level of yellowing than those which were not (Control, Magnesium, Sulphite of Iron).

Conclusions and Discussion

Overall, the trial groups with the highest plant success are Media*2 (the most open media) with an extremely low yellowing rate, Mycelium with an extremely high average number of shoots per pot, and Exposure*2 (wind breaker wall and extra shade) with a high number of shoots and low rate of yellowing.

We were happy to observe that the relationship between our variables and yellowing rate/shoot number was statistically significant (p<0.05) through multiple tests. This further indicates that the dieback events that occurred were very likely down to cultural variables, and it is most probable that our collection had not responded well to division in its first year and suffered because of this.

It was also interesting to observe that provenances were associated with rate of yellowing. The Craighall provenance demonstrated the highest level of yellowing, with most of the ‘moderate’ yellowing also being attributed to this provenance. This indicates that the population the wild samples were taken from likely is genetically poorer and may not be as resilient as the other provenances in our collection.

The results overall demonstrated that an additional level of shading decreased yellowing levels across all trial groups. This aligned with the team’s initial hypothesis on shade decreasing yellowing rate, likely as the P. verticillatum plants are in a growing environment closer to its natural habitat, in woodland floors with dappled shade. It may be for the same reason that the most open media with very high drainage is successful for the P. verticillatum, as this plant typically thrives in the wild in moist yet well-drained acidic soils. The results of this mini-trial indicate that the ideal growing conditions for P. verticillatum is open humus-rich woodland soil mix with high drainage, in a deep shaded area shielded from wind exposure.

It is also interesting to observe that the P. verticillatum inoculated with mycelium had a high number of plant shoots per pot. This may be due to the mycelium making nutrients more accessible from the soil which could boost plant vigour overall. Naturally, P. verticillatum coexists with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in wild populations, demonstrating that these connections are beneficial for P. verticillatum growth. However, as this trial group was smaller (only 35 pots, seen in Table 1), it may be that a larger sample size is needed to accurately compare the ‘Mycelium’ group with the others.

Data will be collected again next week – recording shoot number, yellowing rate, and additionally seed information. It will be interesting to see if any trends or effects of variables will change over time. We all have our fingers crossed that our P. verticillatum collection will remain healthy for translocating out soon!

Potential issues arise from the mini-trial not being totally statistically sound, due to differing numbers of pots per trial, and only approximate estimates of yellowing and counts of shoots. Ranges were used to make data collection viable in a tight timeframe. Where possible, proportions were used to more accurately compare the groups to each other (such as average number of shoots per pot). Nonetheless, this approximation of the data allows us to visualise the difference between the trial groups and investigate in detail the influence of the variables on our plants.

By Erin O’Hare

Special thanks to Becca Drew Galloway (Project Lead Horticulturist) for designing and implementing the Polygonatum verticillatum experimental trial.

This project is supported by the Scottish Government’s Nature Restoration Fund, managed by NatureScot.

Instagram @rbgescottishplants

X @TheBotanics

X @nature_scot

X and Facebook @ScotGovNetZero

Facebook @NatureScot

#NatureRestorationFund