In biogeographic circles everyone likes a good line and no I’m not talking about illicit substance abuse.

Biogeographers draw lines on maps to divide geographic area and to help explain the patterns of diversity that we find. Probably one of the best known of these is the Wallace Line that divides the faunal components of S.E. Asia. The line was first drawn in 1859 by Alfred Russel Wallace, recently getting some well deserved credit for his work pioneering work on evolutionary and biogeographical theory .

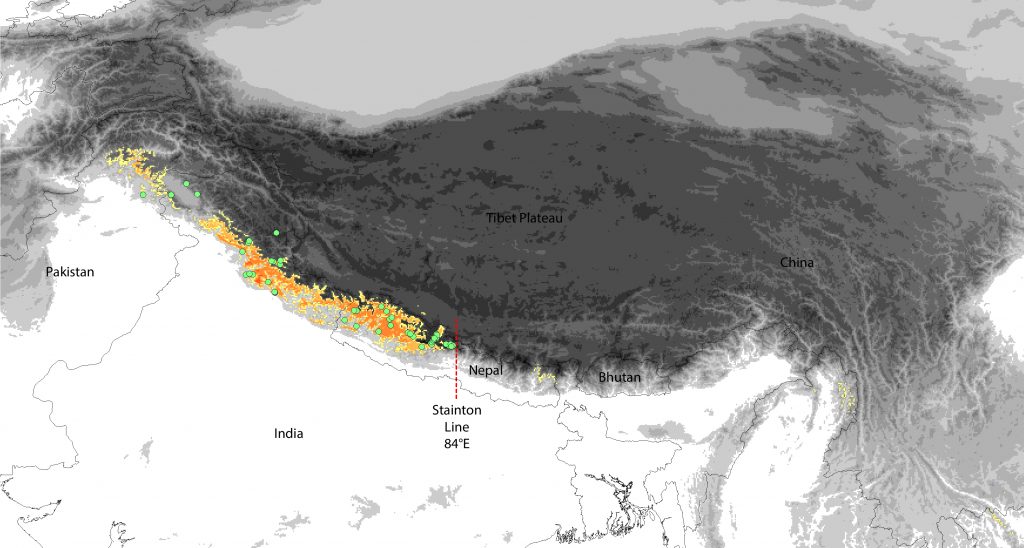

In Himalaya where I focus my studies we have one of these lines, albeit much less well known than Wallace’s Line. This line in Nepal is at about 84°E and was first described by Adam Stainton in this book on the Forests of Nepal in 1972. He noticed that at this longitude there is a mix of different plant species. Also west of the line the species were more like those found in Eastern Turkey and the mountains of Central Asia whereas to the east of the line the plants shared similarities with those in S.W. China, Japan and East Asia. The Stainton Line is very much East meets West in the Himalaya.

Adam Stainton (1921-1991) was able to self-fund collecting trips to the Nepal, Chitral, Greece, Turkey and North Borneo over a period of 30 years from 1954. His legacy to the Flora of Nepal are the 5400 specimens collected with William Sykes and John Williams on the sucessful joint British Museum & Royal Horticultural Society expedition to 1954 and then a further 4800 specimens collected by Stainton himself on numerous additional trips to Nepal. He also contributed to the Enumeration of the Flowering Plants of Nepal and co-authored, what is even now very useful pictorial field guides to the flowering plants in the Himalaya.

When Stainton died in 1991 the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh was gifted his field images. These have been subsequently scanned by digitisation team and linked to his herbarium collections we have here at Edinburgh.

Back to the Stainton Line. The change in species composition has been linked to the rain shadow effect caused by the Anapurna Himal. This mountain massif includes Anapurana I at 8091m and thirteen aditional peaks over 7000m in altitude. The height of the Himalaya here blocks the progress of the monsoon and causes the clouds to dump the bulk of their moisture to the south and southeast causing a significantly drier area to the northwest.

This marked difference in levels of precipitation NW of 84°E has limited the ability of wet and dry adapted species to find suitable habitats on the “wrong side” of the line. However it is not an even split. The western elements abruptly stop at this point but some the eastern elements carry on westward but become much less dominant and eventually fizzle out.

Stainton’s Line is illustrated as the red dashed line. Distribution of known specimens of Clematis grata (Green Dots). The “hot” colours (Yellow to Orange) are the modelled distibution of Clematis grata from those known specimen. This highlighed area is the most likely to support this species based on 19 climatic variables and altitude.

The map above illustrates quite nicely that the ecological preference of Clematis grata is west of the Stainton’s Line. It also clearly demonstrates that Stainton’s detailed field observations done during his 30 years in Nepal are verifiable using modern computer based analysis techniques.

The genus I chiefly work on, Clematis, has a number of these West Himalayan Elements including a few that are only found in Nepal. All exhibit the same basic pattern shown in the map.

- Clematis grata occurs from Afghanistan to the Stainton Line

- Clematis barbellata from Pakistan to the Stainton Line

- Clematis royleii from N.W. India to the Stainton Line

- Clematis tibetana subsp. brevipes is only found in Mustang and Manag districts of Nepal, just west of the line

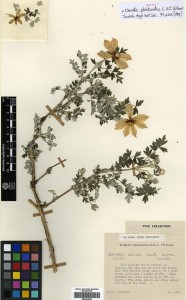

- Clematis phlebantha (pictured above) is restricted to Dolpo District in Nepal where it was first collected and photographed by Stainton in 1963.

Another important factor that I havent been able to model in, but have (I think) accounted for is wind. Anyone who as grown a Clematis at home will have seen the fluffy seedheads that allow thes seeds to disperse. The seeds are attached to a feather-like tail that allows the seed to be carried by the wind. Preliminary analysis of these species seems to show that the time they are in fruit is correlated the prevailing wind.

The summer monsoon blows east to west meaning those that fruit at this time have their seed blown further west to habitats that already suit these species. Others that fruit during the winter monsoon, which blows north to south, have their seed blown into unsuitable tropical and sub-tropical habitats that they are not adapted for. So the inability to disperse beyond Stainton’s Line is linked to the prevailing wind and the species’ preference for the dry west end of the Himalaya.

I find this kind of thing really interesting and this is just one story, of one small group of plants from the megadiverse Himalayas. So what I’m saying is there is lots more to do and many more stories to tell.

1 Comment

1 Pingback