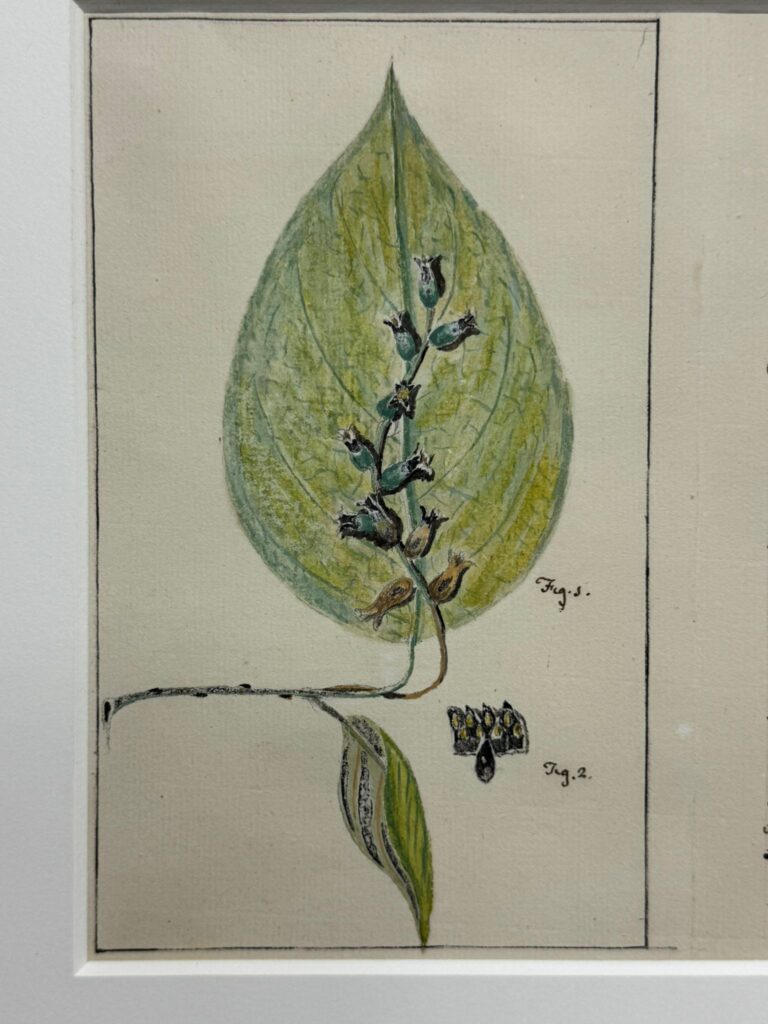

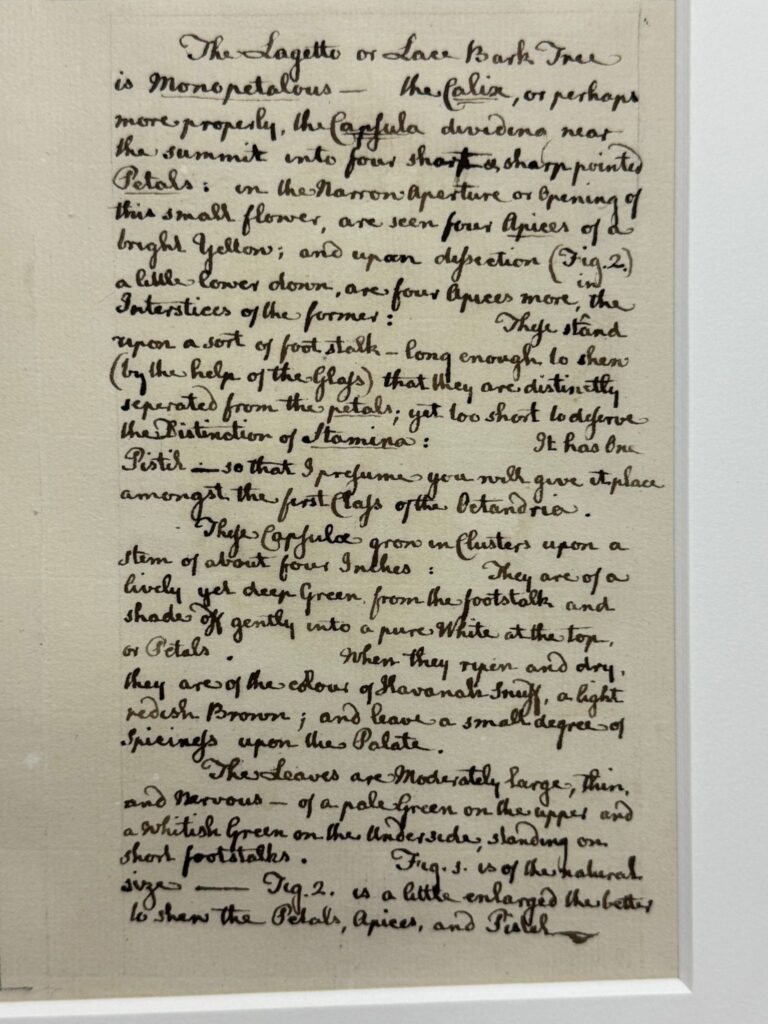

The jeweller Susan Cross from Edinburgh College of Art has been in the herbarium recently working on a project about lace. This brought to mind a ‘natural’ source of the fabric, the inner bark of the Jamaican tree Lagetta lagetto of the family Thymelaeaceae, which I first encountered when studying the life and work of John Hope (1725–1786), the great Enlightenment period Regius Keeper of RBGE. Miraculously the collection of drawings used in Hope’s innovative botanical lectures has survived, among which is a watercolour and description of ‘The Lagetto or Lace Bark Tree’

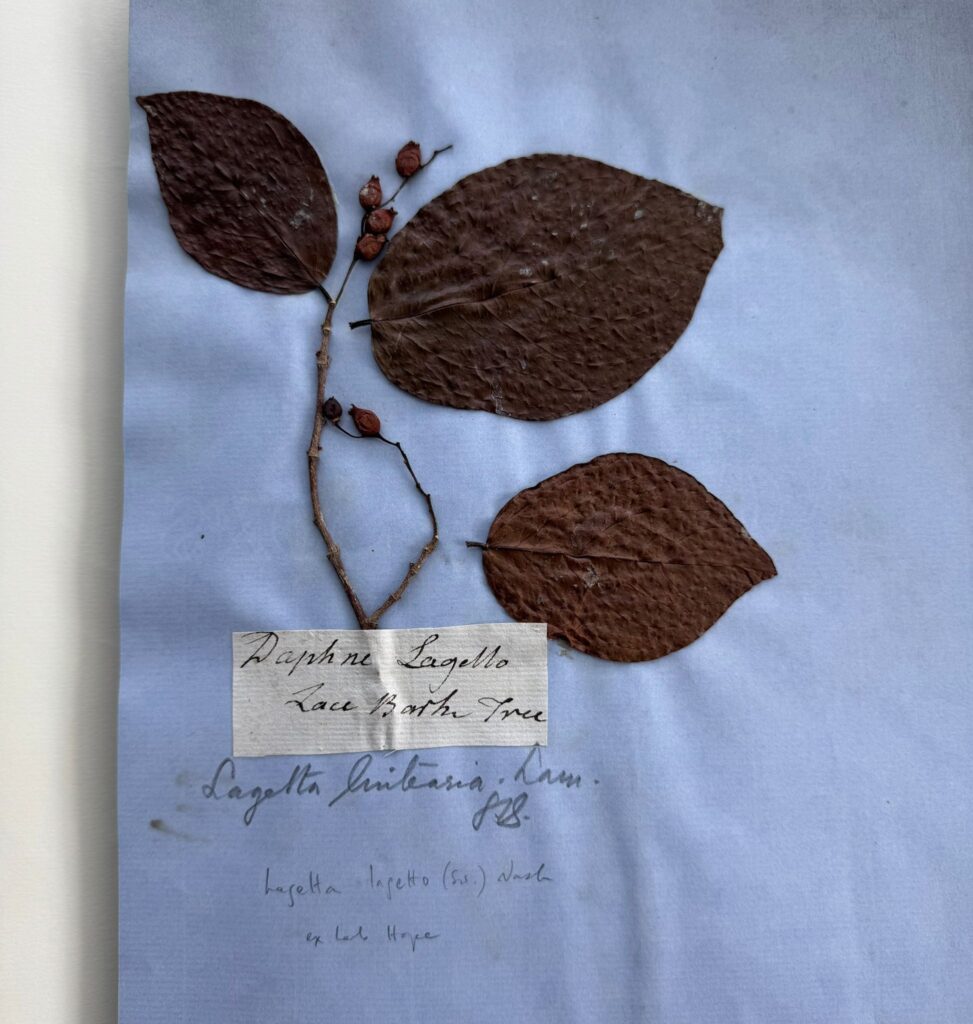

The author of the drawing and accompanying description is regrettably unknown – it was neither of Hope’s major Jamaican correspondents William Wright or John Lindsay, but Dr Thomas Clarke is a possibility. Whoever it was also sent Hope a specimen, which is one of only a tiny handful of specimens to have survived from his herbarium

Long known as a curiosity it had yet to receive a binomial in Hope’s lifetime, but was described and illustrated in ‘pre-Linnean’ literature including the natural histories of Jamaica by Sir Hans Sloane (1725) and Patrick Browne (1756). While on the island in 1687/8 Sloane, who also recorded the name bois dentelle, was told that ‘King Charles the Second [reigned 1660–85] had a cravat made of it presented to him by Sir Thomas Lynch Governor of Jamaica’; Browne recorded that ‘it has been, upon occasion, made into different forms of apparel, by the wild and runaway negroes’.

In 1788, two years after Hope’s death the first binomial for the lace bark Daphne lagetto was published by Olof Swartz in his Nova Genera & Species Plantarum seu Prodromus Descriptionem Vegetabilium, Maximam Partem Incognitorum quae sub Itinere in Indiam Occidentalis Annis 1783-87 Digessit. The following year, in his epoch-making work based on a natural system, his Genera Plantarum, Antoine Laurent de Jussieu described the genus Lagetta; but while quoting the local name ‘Lagetto’ failed to make a binomial. His compatriot Lamarck did so with Lagetta linearia in 1792 but it was not until 1908 that George Valentine Nash, using then evolving rules of botanical nomenclature, combined the earliest available epithet with Jussieu’s genus to make Lagetta lagetto. It was by the merest whisker that Nash avoided a tautonym or double name that in botanical, as opposed to zoological, nomenclature is unaccountably unpermissable.

Doilys (or d’Oyleys)

When I was a teenager Edinburgh was a mecca for its antique shops, but on moving to the city in 1986 they were already starting to become an endangered species. First, container-loads of artefacts were shipped abroad, leaving little to be sold at home, and then e-Bay took over. A few stalwarts, notably Walter Gordon and Peter Powell of ‘The Thrie Estates’ held out, and near RBGE we are fortunate that an outstanding exception to the tide still survives in Duncan & Reid, run by Susie Reid (who comes from a dynasty of antiquarians). It was in Susie’s shop many years ago that I found an octagonal paper folder containing a set of six doilys that incorporated lace bark, which I bought as fascinating ethnobotanical artefacts, without giving much thought to their origin.

Then in 2019 came the publication of Fern Albums and Related Material by Michael Hayward & Martin Rickard. Among the ‘related material’ the authors discuss these sets of decorative souvenirs made in Jamaica between the 1870s and 1920s under the spelling ‘d’oyleys’.

This was sometimes used in Jamaica supposedly in commemoration of Edward D’Oyley, first Governor of Jamaica in the late 17th century, though other D’Oyleys have been suggested as the origin of the word when used either as an adornment to clothing, or for ornamental mats.

Hayward and Rickard also provided a fascinating reference: the Rev Canon E. Jocelyn Wortley’s 1906 Souvenirs of Jamaica: Notes on the Manufacture of Curiosities & Other Souvenirs, which gives details of the botany and handicraft processes involved. The doilys were made as part of a charitable programme to empower women by generating their own income. The basic framework is of the lace bark, with additional ornamental components, especially pressed ferns, attached with starch paste or gum Arabic. They were then doused with alum to repel insects, which accounts for their longevity and pristine condition.

The decorative brown borders in the examples shown here are made from the spathes of the mountain cabbage palm Roystonea altissima, a Jamaican endemic.

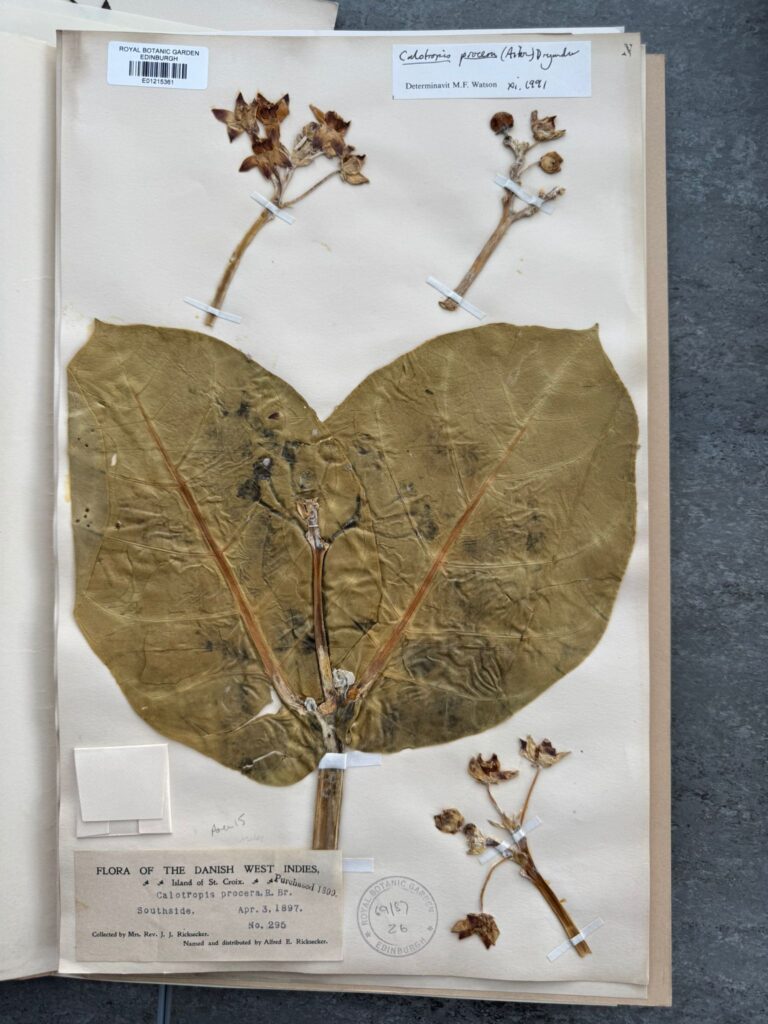

The silky fringe is made of ‘French Cotton’ from the coma of the seeds of the asclepiad Calotropis procera.

This is not native to Jamaica, an introduction from south and southeast Asia – a curious parallel to unhappy human ‘introductions’ as the welfare of indentured labourers from the Subcontinent was one of Wortley’s major concerns. The cochineal-coloured fragments are not petals as I initially thought but squamules of a scarlet lichen. For the ferns Wortley gave no scientific names but those with the common names of gold, silver, stag, tongue, filmy and fish-tail, can all be seen in the six doilys. Fragile and hard to display I have put two of them in a glazed, art-nouveau tray rescued from a skip.

Susan Cross

Thank you Henry for bringing in these extraordinary collaged structures that integrate the Lace Bark Tree in such a creative and decorative way. Such an intricate fine lace like structure and all made naturally! The origin of them is interesting too.

I certainly am enjoying this fascinating journey with my lace project, so many wonderful plant specimens and illustrations to be inspired by here at the RBGE.