An internet search for Sutherland kale produces quite a lot of hits. This leafy brassica seems to be a bit of a sensation among foody types looking for something a bit different. Apparently the best way to eat it is to steam the flower spikes before the buds open. They look like a rather spindly version of broccoli and have a delicate sweet taste, making a very passable substitute for asparagus.

When the Edible Gardening Project here at the Garden started growing this plant I became rather intrigued by it. The name suggests it is a type of kale, which in botanical terms would mean it is a form of Brassica oleracea, the ancestor of many familiar vegetables including cabbage, kale, broccoli, brussels sprouts, cauliflower and kohlrabi. The problem is that the leaves have hairs on them, albeit very sparsely. As Brassica oleracea, and its derivatives, are completely hairless this seems to suggest that Sutherland kale is actually another species of brassica.

Sutherland kale leaf showing the tell tale hairs that suggest it is not a form of Brassica oleracea.

A quick bit of research confirmed that the most useful identifying characteristics were to be seen in the flowers themselves and their position in relation to unopen buds in the flower spike. This meant a bit of a wait as my interest had been aroused in the autumn!

Having now looked at the flowers the evidence would point to Sutherland kale being a form of Brassica napus, which is most familiar as the oilseed rape that paints the countryside yellow when it flowers. The key features are that the open flowers do not overtop the unopen buds and that the sepals (green structures at the base of the flower) are at a roughly forty five degree angle to the axis of the flower stalk.

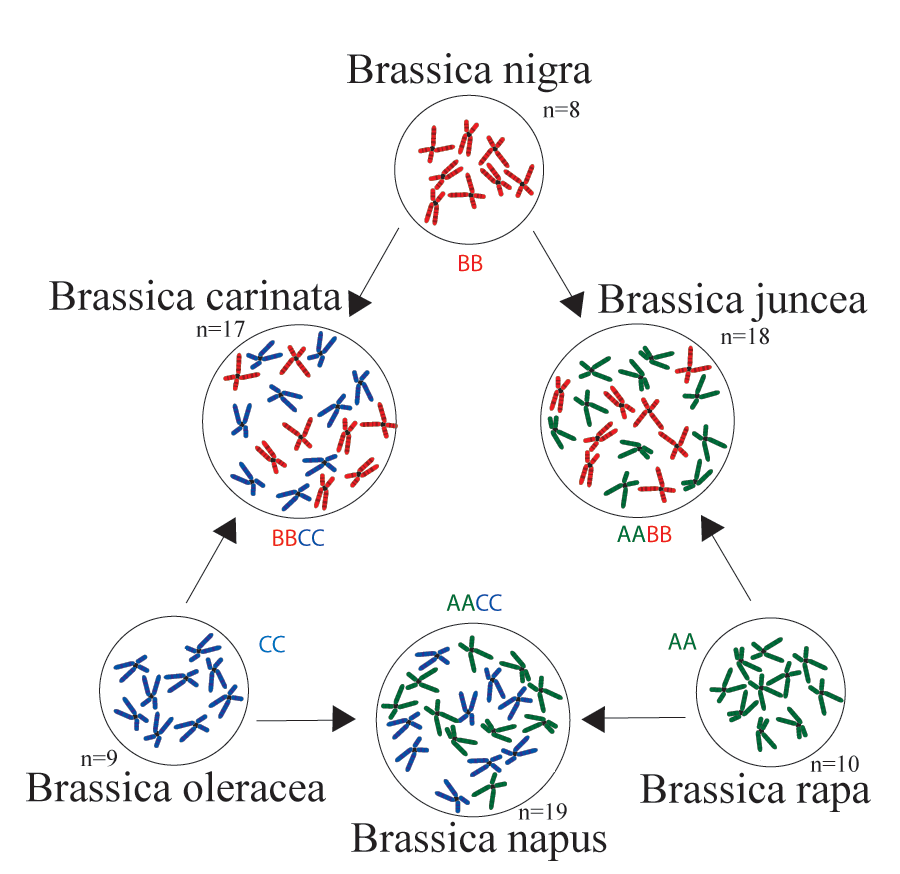

However, the story does not end there as the origin of Brassica napus is in itself a textbook case of humans modifying nature to produce food. Korean-Japanese botanist Woo Jang-Choon published a theory about the origin of Brassica napus and two other species via hybridization between cabbage, turnip (Brassica rapa) and black mustard (Brassica nigra). These three wild brassicas form the corners of a diagram that became known as the Triangle of U (U is the Japanese equivalent of Woo).

Woo examined the chromosomes of the presumed parents in these crosses and also created artificial hybrids. His ground breaking work, published in 1935, has been subsequently confirmed by analysis of proteins and DNA.

hanna testroet

very interesting! I have grown sutherland kale and also noticed that the leaves resemble turnip leaves much more than cabbage, so had my suspisions. But its not officially known, the latin classification?