Protection of the habitat is a perhaps the most effective method of conservation of plant diversity, yet this alone cannot guarantee the survival of some of our most threatened species. Changing climate, the introduction of new predators or diseases, and many other factors can affect the survival of a small population. To best achieve success in conservation, knowledge of the plants’ biology, its life cycle and population structure together with information on the reason’s for decline of a population are all essential ingredients for the maintenance of a population. A strategy for conservation for one species may differ considerably from that of another species.

Two fern species have been the subject of conservation programmes by two of our Research Associates, Mary Gibby and Heather McHaffie. What they share in common is the reason for their past decline; both were targets of enthusiastic collectors, especially during the second half of the nineteenth century, when the Victorian fern craze – so-called “Pteridomania” – was at its height. The ferns were sought out for private collections of pressed specimens or for cultivation, often in glazed Wardian cases, to ornament elegant drawing rooms.

Mary Gibby – First female Director of Science at RBGE (left)

Heather McHaffie– former Scottish Plants Officer at RBGE

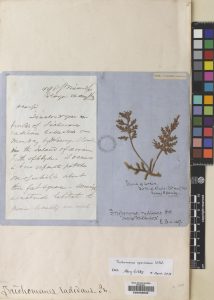

We have good documentary evidence of the decline of the two species, preserved for posterity in the herbarium at RBGE. Although RBGE was founded in 1670, the establishment of the herbarium dates from 1873 when the collections of the Botanical Society of Edinburgh (B.S.E., now the Botanical Society of Scotland) were donated to the Garden. Amongst the plants collected by members of this august society is small specimen of the Killarney Fern, Trichomanes speciosum, the first record of this plant from Scotland. It was discovered in 1863 by Robert Douglas, the ‘walking postman’ of Arran. His find was confirmed by the Edinburgh naturalist W. B. Simpson, who suggested that Douglas should keep the information secret. Douglas, however, showed the site to George Coombe of Glasgow, who returned and stripped the site almost bare. The annotated herbarium sheet (Figure 1) with two small fronds includes a letter from George Coombe.

Figure 1: Trichomanes speciosum (Killarney Fern)

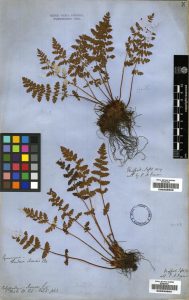

The decline of Oblong Woodsia, Woodsia ilvensis, is linked closely to the opening up of the railways. A major centre of the distribution of this little plant was the hills around Moffat, in southern Scotland, and fern enthusiasts were so keen to acquire specimens that a trade in the plant grew up for visiting tourists at Moffat station. In a report of a plant hunting trip by a few friends from the B.S.E., they describe after a very long search finding five plants of the Woodsia, four of which they collected, leaving one behind as “an egg in the nest”! Two large pressed whole plants from this expedition are on the sheet in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Woodsia ilvensis (Oblong Woodsia)

Both ferns are of conservation concern in the UK, and the Killarney Fern is included in the EU Habitats Directive. In Species Action Plans developed in the 1990s, it was proposed that for both species conservation action through restoration should be considered. Study of the biology of the Killarney Fern has shown that the fern has two distinct and long-lived forms to its life cycle; the normal spore bearing fern (sporophyte) with a creeping rhizome is confined to very humid, shady conditions usually below 50m altitude, whilst the gametophyte generation, with a green filamentous structure that bears the sex organs, thrives in deep crevices, and under very low light conditions. Whilst the distribution of the fern is extremely limited, being confined mostly to a few sites in western Britain and Ireland, the gametophyte is much more widespread, on the north, south east and west coasts of the UK, and the gametophyte populations carry much more genetic diversity that that remaining in the few sporophyte populations. The gametophytes are a living spore-bank that has the potential to give rise to further sporophyte populations under warmer and wetter conditions. Re-introductions have been deemed inappropriate for this species.

There are now fewer than 100 plants of Oblong Woodsia in the UK. One population near Moffat has been seen to decline from c. 25 plants down to only three in the last forty years, and with the exception of a population of over 60 plants in England, many of the Scottish and Welsh populations are limited to less than six plants. It is still unclear why the species continues to decline, and why new plants are failing to establish. Andrew Ensoll has had great success in establishing a very large ex-situ collection at RBGE of the species from spores collected under licence from throughout the species’ range. With the support of Scottish Natural Heritage and Natural England several new populations have been established in areas where the species has been lost, and these continue to be monitored. There has been fairly good survival of these re-introductions, but despite some having been established for 15 years, there is still no evidence of natural regeneration in the wild.

One of the few plants left of Woodsia ilvensis growing wild in Scotland

The next generation of females in science takes this work forward – Nadia Russell, a PhD student based at the Garden, is carrying out further research on the genetics of the species to see whether genetic rescue is feasible.