The story and fate of the fourth of Sir John Franklin’s expeditions in search of the North-West Passage, on the ships Erebus and Terror in 1845–8, is well known. It has a connection with my current work on Hugh Cleghorn, as the young surgeon-naturalist on HMS Erebus was Harry Goodsir, an Anstruther friend from Cleghorn’s childhood. Harry’s brother Robert Anstruther Goodsir went on two of the voyages in search of his brother and his compatriots – and Robert’s tombstone is one of two with Franklin connections in Edinburgh’s remarkable Dean Cemetery. It has recently emerged that Harry’s skeleton may be the one returned to Britain and buried at Greenwich wrongly identified by Thomas Henry Huxley in 1872 as that of Henry Le Vesconte.

The story and fate of the fourth of Sir John Franklin’s expeditions in search of the North-West Passage, on the ships Erebus and Terror in 1845–8, is well known. It has a connection with my current work on Hugh Cleghorn, as the young surgeon-naturalist on HMS Erebus was Harry Goodsir, an Anstruther friend from Cleghorn’s childhood. Harry’s brother Robert Anstruther Goodsir went on two of the voyages in search of his brother and his compatriots – and Robert’s tombstone is one of two with Franklin connections in Edinburgh’s remarkable Dean Cemetery. It has recently emerged that Harry’s skeleton may be the one returned to Britain and buried at Greenwich wrongly identified by Thomas Henry Huxley in 1872 as that of Henry Le Vesconte.

My interest in Frankliniana has been revived with a visit to the herbarium by Adriana Craciun from the University of California. She is here primarily to research a story from an altogether more torrid region of the globe (the supposed germination of wheat and peas found with Egyptian mummies in the mid-nineteenth century), but has recently published a book about Arctic exploration (Writing Arctic Disaster: Authorship and Exploration, Cambridge University Press, 2016). The travails experienced by members of Franklin’s first ‘Overland’ expedition of 1819–22 form one of the most harrowing tales of deprivation and endurance in the history of exploration: hopelessly badly provisioned, they trusted to help from ‘Indians’, ‘Esquimaux’ and Canadian ‘voyageurs’ (porters/hunters), to employees of two trading companies who turned out to be at war with each other, and on being able to live off the land from game shot and plants collected. The result, combined with the extreme environment encountered on the journey back from the ‘hyperborean sea’ in the autumn of 1821, was scarcely surprising: starvation, death, murder and cannibalism. One of the voyageurs employed by Franklin was clearly driven to insanity and shot two of his companions; he then brought back pieces of what he claimed to be ‘wolf’ meat to the surviving members of the party, which actually came from the bodies of his murdered companions. Only 9 of the 20 men returned, though only one of the five Britons lost his life. The survivors were forced to eat not only their boots, but rotting deer corpses (bones and all) and discarded caribou hides infested with the maggots of warble flies – the tastiest morsels, which tasted like ‘gooseberries’. The only vegetation obtainable during the arctic winters, and which had to be dug out from under feet of snow, were occasional berries and lichens of the genus Gyrophora (now Umbilicaria), which they called, perhaps ironically, as though from a French menu, ‘tripe de roche’.

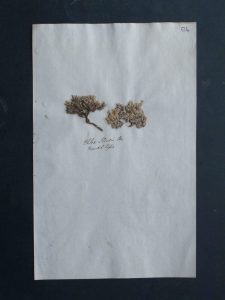

A type sheet, from George Walker-Arnott’s herbarium, of Phlox hoodii, the plant chosen by John Richardson to commemorate his murdered colleague.

The surgeon and naturalist on the expedition was John Richardson (1787–1865) from Dumfries, who had an Edinburgh MD, and may have studied botany at RBGE under Daniel Rutherford. In 1823 he published in an appendix to Franklin’s account of the expedition an account of the plants that (remarkably) he had managed to send back – in writing this Richardson had help from William Hooker and Robert Brown. I knew that there was Franklin material in the herbarium (a lupin specimen was reproduced in the Botanical Treasures book), but Adriana’s visit prompted a search for more, in particular for types of Richardson’s and Hooker’s new species – one of my favourite activities is what might be called ‘herbarium angling’. It turns out that there are Richardson/Franklin specimens in no less than four of the numerous individual collections that make up our vast and complex herbarium: Archibald Menzies (probably given to him directly by Richardson) and in the herbaria of George Walker-Arnott, Robert Kaye Greville and William Gourlie. Arnott and Greville were collaborators with, and Gourlie a Glasgow-friend of, Hooker, so their specimens are probably duplicates from the material given to Hooker by Richardson. Unfortunately the specimens are not numbered and usually have no details other than ‘Franklin Exped’. Some of the specimens undoubtedly come from the second expedition (on which Thomas Drummond was the botanist), but what are most probably types (previously unrecognised as such) of 20 species of flowering plants, and two lichens, from the first expedition have been discovered.

Of the types the most interesting are two sheets of Phlox hoodii. This is the plant that Richardson chose to commemorate the 24-year old Robert Hood, the artist of the expedition, who while consoling himself by reading Edward Bickersteth’s Scripture Help was the third victim of the Iroquois voyageur, Michel Terohaute, shot through the back of the head and doubtless intended to be eaten. Terohaute in turn was executed by Richardson. Knowing the story behind them, it is moving in the extreme to contemplate these small cushion plants, turned into specimens, mounted on large sheets of paper, like islands adrift in a sea of blue ice.

Umbilicaria pennsylvanica, specimens given by Richardson to Archibald Menzies – one of the lichens eaten by the party.

Equally stirring are the lichen specimens, which resemble small fragments of the shoe leather that also had to be consumed. Two of the 120 species collected were described as new by Hooker (one being Cetraria richardsonii commemorating the indomitable botanist, who returned with Franklin on his second ‘Overland’ expedition, and launched the first search for his friend in 1848). And in Greville’s and Menzies’s herbaria are specimens of four of the species that expedition members were reduced to eating. Of these Richardson commented: ‘we used them … as articles of food, but not having the means of extracting the bitter principle … they proved noxious to several of the party producing severe bowel complaints. The Indians use the G[yrophora] Muhlenbergii … and when boiled along with fish-roe or other animal matter, it is agreeable and nutritious’. Sadly the men did not have the luxury of the caviar ‘palatizer’, and G. vellea, which was somewhat ‘more agreeable’, was obtainable only ‘very sparingly on the Barren Grounds’, i.e. the tundra.

Other fascinating things have emerged from this brief foray into Arctic history. The RBGE copy of the first edition (1823) of Richardson’s separately printed botanical Appendix to Franklin’s official expedition account is inscribed from the author to Robert Graham (RK of RBGE 1820–45). It is covered in manuscript additions and corrections in Richardson’s hand, which were mostly incorporated into the second edition of later in the same year. It also turns out that Eutoca (now Phacelia) franklinii was grown in a cold frame at RBGE, from seed given by Richardson to Graham, and described by the latter in the Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal of 1828.

Now read part 2: Nordic ‘alimentation noire’: a culinary experiment, RBGE Canteen, 29 June 2016

Dr Dora Thornton

How moving to read the story behind the naming of Phlox Hoodii. which contextualises the RBGE holdings in a completely new way. Fascinating.