Background to the project.

The advent of the era of Big Data has highlighted a truism in scientific discovery: an inference is only as good as the data that underlie it. While it is tempting to believe that large, open-access data repositories are a recent invention, in fact scientific collections such as herbaria have been filling this purpose for hundreds of years. But, while the data in these collections are nearly always open (e.g., the Royal Botanic Garden Herbarium has shared specimens with any who so request since at least the 1960s), they are not always accessible. Even when collections have been digitised and made freely available over the internet, a lack of taxonomic knowledge, awkward user interfaces, or simply ignorance of the scope of scientific collections inhibit their use by scientists and the general public alike.

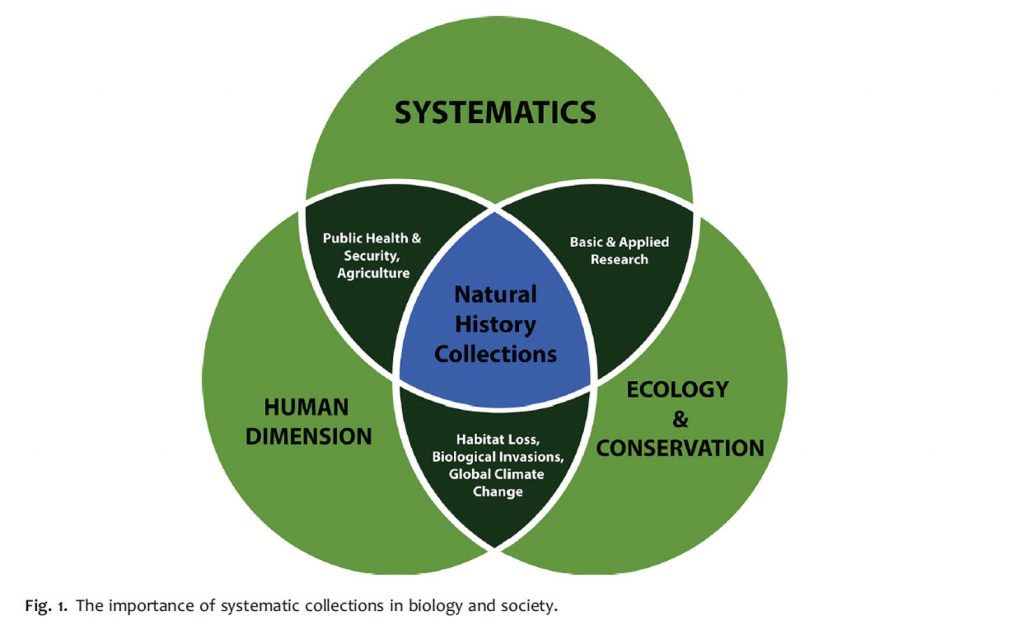

To bridge the gap, scientific collections must be made visible and accessible to different communities of scientists working outside the immediate research area and the lay public, allowing the collection to reach its full potential value:

- to support narratives that connect the scientific collection to datasets outwith the immediate area of research (for example, other sciences, government records, and/or social media)

- to enable fine-grained narratives interacting with lesser understood specimen, collectors, geography and time periods, and,

- to investigate archival practices that we might better support these narratives.

Here is a video (1.09 mins) explaining the project by the RBGE project partner Katherine Hayden.

The project uses the collections of the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh Herbarium as a laboratory, to produce contemporary online material that illuminates and enhances the collections of the RBGE.

Why Herbarium Collections?

Herbarium Collections – a collections of plant specimens and associated data used for scientific study and for species definitions – tell stories of a particular time and place, and have been collected for several centuries (Miller-Rushing, Primack & Bonney 2012). Most obviously, they are a physical representation of the plants that made up the landscape. They can, however, also track movements of a particular collector and tell the story of a journey, or, over time, the story of shifting climates. We aim to make these stories visible via a proof of concept project that will form links between the collections, their stories, and the present through geo-referenced images on social media.

In all areas of research datasets play a crucial role, and, increasingly, we are becoming interested in connecting up datasets, re-framing datasets to meet the needs of different contexts, and opening up the dataset to an audience beyond its context of creation. We expect the final gallery to be of interest to the general public, as a narrative and interactive history. It will likewise be of use to historians of science, to climate change science, to land use studies, and to botanists.

From: Collections-based systematics: Opportunities and outlook for 2050 by Jun Wen et al. in J. Syst. Evol. 53 (6): 477–488, 2015

From: Collections-based systematics: Opportunities and outlook for 2050 by Jun Wen et al. in J. Syst. Evol. 53 (6): 477–488, 2015

There is an urgent need for new innovative ways to facilitate cross disciplinary research and cross-sectoral development that goes beyond the original community of stakeholders. The rapid growth of data complexity – volume, variety, and multiple rights, ownerships, protection laws – has scientific, cultural and legal implications that affect each other.

The project as a whole has the following objectives:

Finding specimen in the herbarium and finalising digitisation of specimen when needed;

- Making herbarium data visible and accessible to different communities of users (scientists working outside taxonomy and systematics) and the lay public(s), thus enhancing open data access beyond its strictly technical meaning;

- Completing geo-references where missing and provide links to social media results for that area. This will contribute to further improving and enhancing the accessibility of the collection through digital story-telling and social media presence;

- Expanding and highlighting lesser-known RBGE herbarium specimens, data (herbarium, living collection, plant info and microbial cultures) and histories, in particular those that are not usually at the core of researchers’ attention and public use;

- Making visible human and non-human ecologies and their material/historical interaction through story-telling, highlighting both frictions and good practices.

The project proposed here brings together several disciplines: data analysis at University of Glasgow; record-keeping and curation at the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh; and, research at University of Aberdeen in the areas such as visual culture of contemporary science, scientific imaging techniques and, public engagement with science through the arts.

And the project is funded by

The text for this post was adapted from the project application to Scottish Crucible and not written by the blog poster .

References:

Miller-Rushing, A., Primack, R. and Bonney, R. (2012) The history of public participation in ecological research. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 10: 285–290. doi:10.1890/110278

2 Comments

2 Pingbacks