I was asked this question on a recent trip to North Ronaldsay and had to plead ignorance. We had been discussing a floral display on the local golf links studded, not with daisies, but with an exquisite form of one of the most beautiful and chaste of all British flowering plants. Its beauty alone entitles it to a name associated with the home of Apollo and the Muses, but what was its history? The version growing there was no more than an inch high – probably the form first described from coastal Lancashire as Parnassia palustris var. condensata.

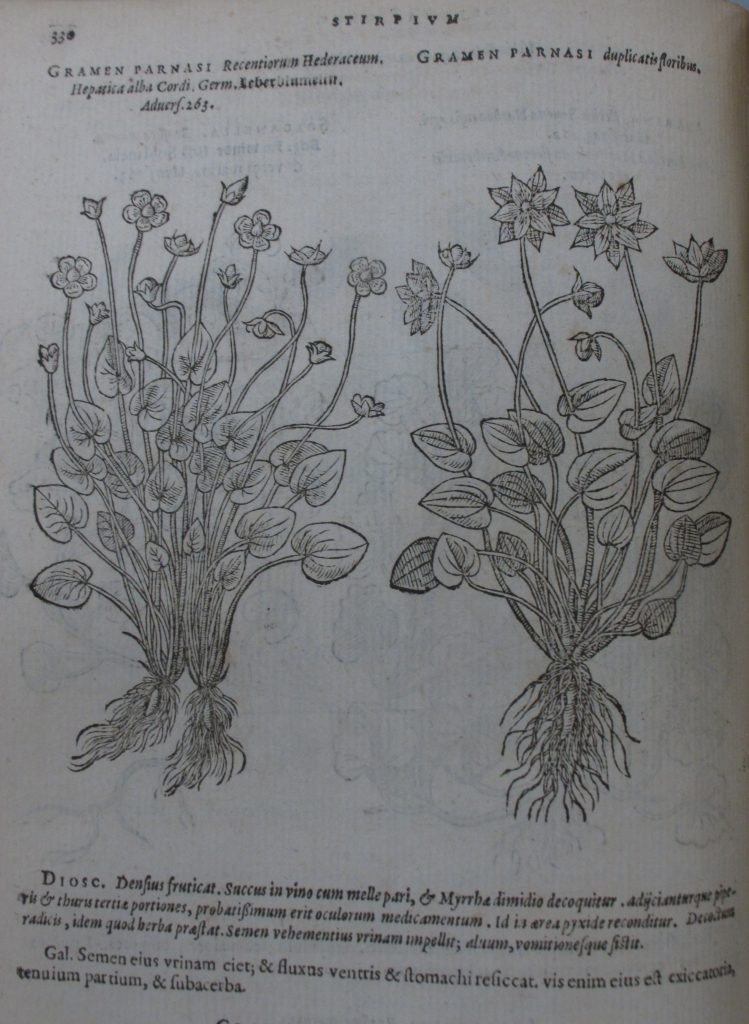

Back in Edinburgh I consulted my beloved copy of Gerarde’s Herball or Generall Historie of Plantes (the second edition of 1633, ‘enlarged and amended by Thomas Johnson’). The names Grasse of Parnassus and Gramen Parnassi are used there, accompanied by a pair of woodcuts of a single- and double-flowered form, with records of the former from Yorkshire, Cambridgeshire, Suffolk, and Northamptonshire, and – closer to home – a record from Johnson’s friend William Broad ‘plentifully in the Castle fields of Berwicke upon Tweed’. But as Gerarde is a synthesis of the works of several earlier authors, illustrated with recycled woodcuts, the search had to continue backwards. I tried Geoffrey Grigson’s engaging and usually authoritative Englishman’s Flora, which claimed that the name was first used in 1570 by Mathias de l’Obel (he of the blue bedding plant).

In fact the name goes back almost two millennia, to classical antiquity. The encyclopaedic Materia Medica of Pedanius Dioscorides of Anazarbus was written in the first century, and ‘Parnassos Agrostis’ forms the subject of Chapter 31 of the Fourth Book. The botanical description is skimpy: ‘It has leaves similar to those of ivy, a white fragrant flower, [and a] small fruit which is not useless’ (in Lily Beck’s translation). It was unfortunately not among the species illustrated in the great manuscript of Juliana Anicia, the earliest surviving Dioscorides manuscript, dating to 512 AD, which since the sixteenth century has been one of the greatest treasures of the former Imperial Library in Vienna, and hence its name Codex Vindobonensis.

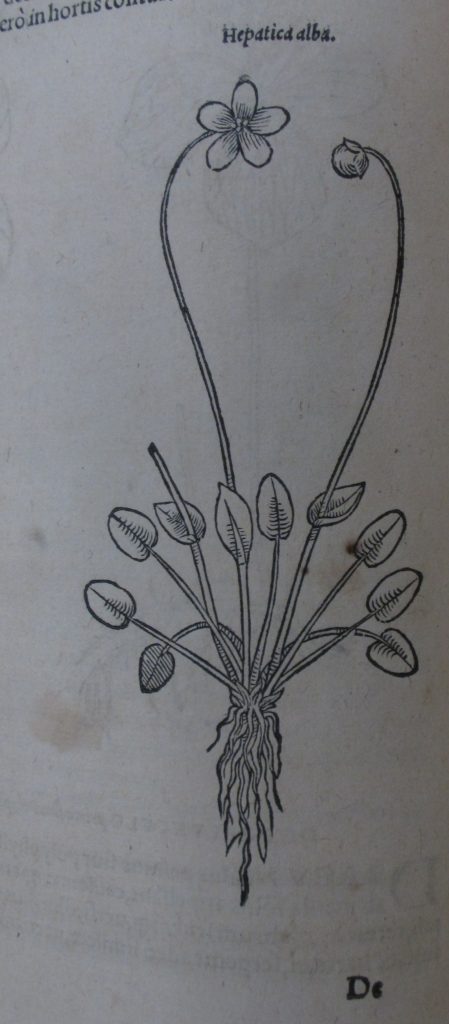

Dioscorides was the pre-eminent medico-botanical text for more than a thousand years, diffused by manuscript copies in Greek, Latin and Arabic, but during the North-European Renaissance, its influence lost ground, though not before attempts had been made, especially in Germany and the Low Countries, to identify the species referred to. It came to be realised that there were huge differences between the floras of northern and southern Europe, and that to have any hope of finding the plants that Dioscorides really wrote about a trip to the Mediterranean would be essential. One of the earliest to attempt this was the German herbalist Valerius Cordus (1515–1544). He got no further than Rome, where he died of fever, but some of his companions reached Naples – a step in the right direction. In his 1541 commentary on Dioscorides he cited the name in Latin form, ‘Gramen Parnasi’, as a synonym, but renamed it ‘Hepatica alba’ for its medicinal use. Although he gave no localities Cordus must have known the plant as he provided the first illustration of it .  L’Obel followed in this tradition, but was not the first to give a version of the name in a modern European language. Credit for this appears to go to the Flemish botanist Rembert Dodoens, who in his Cruijdeboeck of 1554, written in Old Flemish, cited Dioscorides and translated the Greek name as ‘Gras van Parnaso’ in Dutch, or ‘Gramen Parnasi’ in Latin. Dodoens also illustrated the plant and gave the first northern European locality – Brabant. In the Stirpium Adversaria Nova of Pierre Pena and l’Obel, printed in London in 1570/1, there is a description but no illustration, and they recorded the first British locality (near Oxford) in addition to Piedmont, Belgium and ‘Northmania’ (?Normandy). For the second edition of the work (1576) l’Obel went to the great Antwerp publisher Plantin who was able to provide the woodcuts of the two varieties that were reused by Gerarde.

L’Obel followed in this tradition, but was not the first to give a version of the name in a modern European language. Credit for this appears to go to the Flemish botanist Rembert Dodoens, who in his Cruijdeboeck of 1554, written in Old Flemish, cited Dioscorides and translated the Greek name as ‘Gras van Parnaso’ in Dutch, or ‘Gramen Parnasi’ in Latin. Dodoens also illustrated the plant and gave the first northern European locality – Brabant. In the Stirpium Adversaria Nova of Pierre Pena and l’Obel, printed in London in 1570/1, there is a description but no illustration, and they recorded the first British locality (near Oxford) in addition to Piedmont, Belgium and ‘Northmania’ (?Normandy). For the second edition of the work (1576) l’Obel went to the great Antwerp publisher Plantin who was able to provide the woodcuts of the two varieties that were reused by Gerarde.

Moving forward to the eighteenth century, another great encyclopaedist, Linnaeus, took the name from earlier sources, and in 1753 made the Latin binomial Parnassia palustris, using an epithet that refers to the plant’s preferred marshy habitat. Interest in classical antiquity was also revived during the Enlightenment, notably in the ancient universities. In Oxford this inspired the young John Sibthorp to travel to Greece, with the artist Ferdinand Bauer, stopping off at Vienna to see the Codex en route. The Flora Graeca took decades to be completed after Sibthorp’s premature death, though the wait was arguably worthwhile, as it resulted in what is generally regarded as the finest of all illustrated Floras (the botanical equivalent to ‘Audubon’). Disappointingly it has no illustration of Grass of Parnassus from its ‘native heath’, nor is it mentioned in the text. Sibthorp did, however, see the plant, on a mountain in Asia Minor – the Bithynian Olympus, now known as Ulu Dagh – as recorded in the Flora’s precursor, the Florae Graecae Prodromus (published in 1806, edited by John Hope’s pupil James Edward Smith).

Despite the brevity of Dioscorides’ description, the traditional identification seems not unreasonable, and the plant still occurs on mountains in Greece, including Mount Parnassos itself, a limestone mountain that rises above Delphi, looking across to the Peloponnese; and also on the home of the gods themselves, Mount Olympus.

Maura C Flannery

Thanks so much for this.

John Fletcher

Wonderful – and I can understand why it might have been considered a white hepatica too.

Maura High

I was looking up Grass-of-Parnassus to find out more about Parnassia caroliniana, the species that occurs in the southwestern United States. The French botanist André Michaux is credited with finding and naming it (as with so many of our other native flora). Our North Carolina species has basal leaves as well as the cauline ones I see in the botanical illustrations here. Lovely to see how many people have been involved in the naming of the plant, and how random and strange some names tend to be.