By Hannah Swan

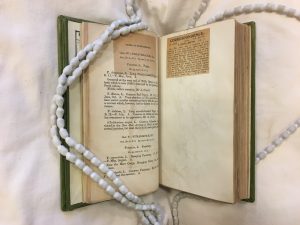

Before publisher’s bindings were de rigueur, texts came in flimsy paper ‘wrappers’, leaving the permanent binding to the new owner. Because of this, many books from the 19th century and earlier include extra pages added by their new owners and interleaved into the text. Sometimes these would include illustrated plates from other sources, other times blank leaves would be inserted so that the owner could take notes without sullying the margins.

Because many of the volumes in the Garden’s collection were used for research purposes, they are often filled with the former owners’ thoughts, observations, and notes. There are also volumes containing herbarium samples. Over the course of these blog posts, I will explore just a small sample of the innovative ways book owners have used these interleavings over the years.

The Flora of Forfarshire by William Gardiner, 1848

Although its 20th century binding is unassuming at first glance, this copy of The Flora of Forfarshire holds a wealth of both provenance information and clever insertions.

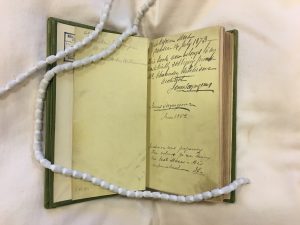

The ink inscription on the flyleaf reads:

Reform Street

Dundee 14 July 1873

This Book now belongs to my most kindly & obliging friend, Mr. Alexander Hutcheson, Architect

James Scrymgeour

June 1852

Gardiner was preparing this volume for me during his last illness–it is unfinished. J.S.

In addition to this volume, the RBGE archives hold several documents related to Gardiner, Scrymgeour, and Hutcheson, which illuminate the process of producing the book and the relationships of the three men. An advertisement for the second edition, dated 1872, is signed by James Scrymgeour. However, it is noted, in pencil, on the top of the advertisement, that the second edition was never, in fact, published, mirroring Scrymgeour’s note on the flyleaf that the volume is unfinished. It is likely that RBGE’s copy is the only extant copy of the second edition.

How Scrymgeour and Hutcheson knew one another is unclear. However, I would like to think that they became friends as a result of their shared love of animals. Hutcheson’s entry in the Dictionary of Scottish Architects states that he was “president of the Food Reform Society (which believed in vegetarianism) in around 1881.” Around the same time, in 1872, the Dundee Post Office Directory lists James Scrymgeour as a board member of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.

Inside the book, even more surprises await…

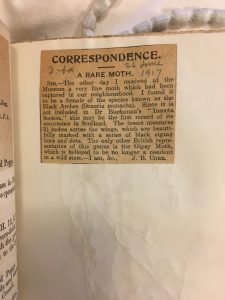

Throughout the text, one of the former owners (likely Hutcheson, based on dates) has pasted in various stories from local newspapers that he found of interest. This story, from 1917, details the acquisition of a rare moth specimen at the museum.

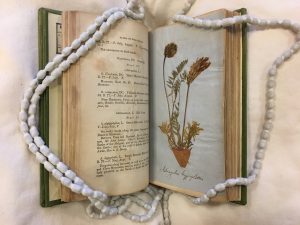

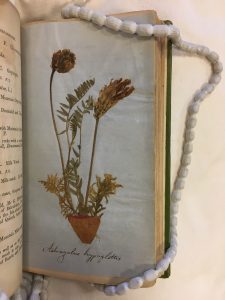

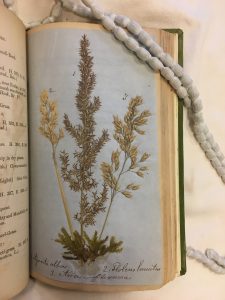

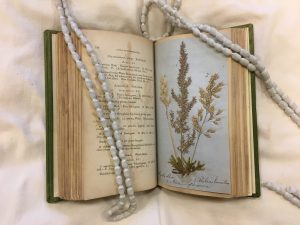

In addition to the newspaper clippings, there are a series of herbarium samples interleaved throughout. Although it is not uncommon to find herbarium samples in items in RBGE’s collections, the whimsy of these samples, with their miniature pots made of paper and leaves, are particularly unusual and charming. A note from Hutcheson included in the archival material states that these specimens were, in fact, made and included by Gardiner himself.

For more information about this volume of Gardiner’s work, you can visit the catalogue record for The Flora of Forfarshire here.

For more information on James Scrymgeour and Alexander Hutcheson, you can peruse various Dundee Post Office Directory records here.