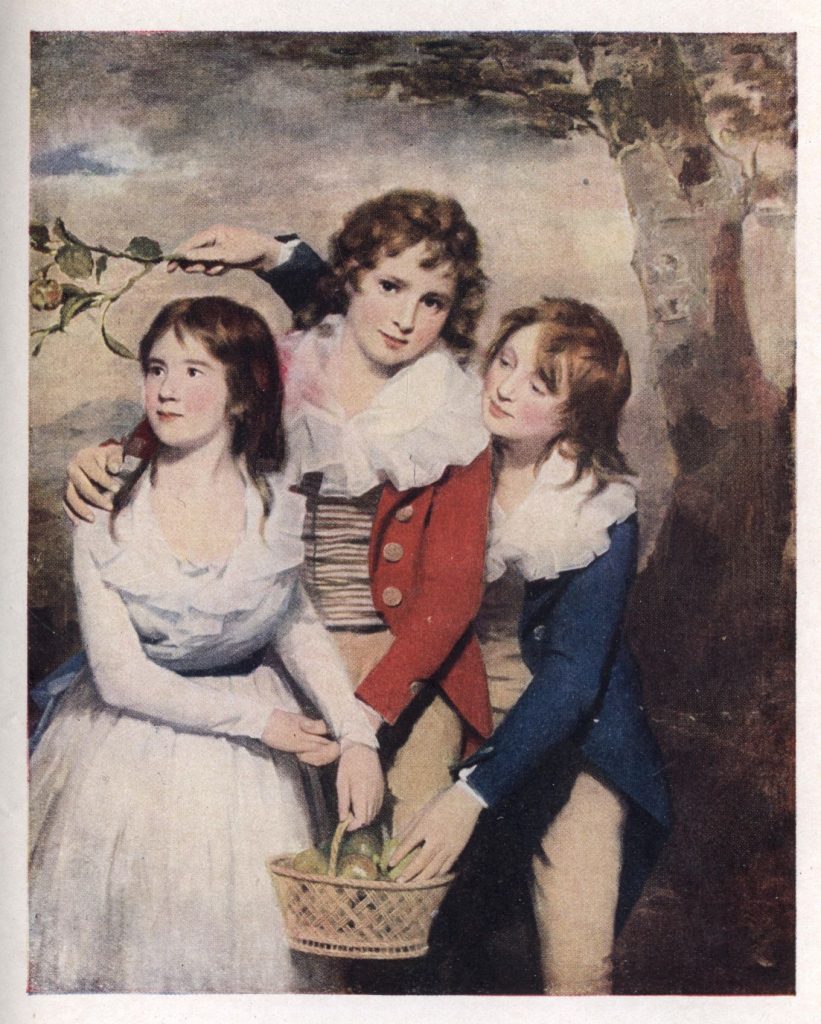

Recently I was looking at the catalogue of the memorable exhibition of Raeburn portraits held in the Royal Scottish Academy in 1997. In it is reproduced a radiant portrait of three children: two young girls, one playing a tambourine the other with a doll, their elder brother rather bizarrely clad, wearing a beret of unidentifiable fur, a string of beads round his neck and a fishing rod slung over his right shoulder. The title of the portrait (lent by the Cincinnati Art Museum) is ‘The Elphinston Children’ and it was not only the striking image that caught my eye. Many years previously I had come across the curious spelling of the surname, with its dropped terminal ‘e’, but in a very different context.

Alexander Gibson’s pioneering work as a forest conservator in the Bombay Presidency in the 1840s was primarily driven by financial motives: to ensure a continuing supply of the teak that was already a diminishing resource for the Bombay dockyards. He was however aware of the deleterious effects of deforestation not only for timber supplies, but on climate and therefore on agriculture and stream-flow. Gibson published comments on this in his 1845/6 annual forest report, and had clearly been discussing the matter with the Collector of Poona, Alexander Elphinston (1801–1888). In February 1846 Elphinston followed this up with two letters to Gibson on the subject, written five days apart from the hill station of Mahabaleshwar in the Western Ghats, where he was laid up with a broken leg. Full of his own acute observations and recommendations the letters draw on Elphinston’s experience of the forests of the Concan coast from the time when he had been Collector of Ratnagiri, and on a more recent visit to the Nilgiri Hills. He told of the desiccation that followed deforestation and recommended the replanting of trees, and their subsequent policing, not only as a source of future timber, but for climatic amelioration. One of these letters was published by Gibson, the other survives as a manuscript in a compilation on the desiccation issue made by Edward Balfour, to whom Gibson had sent it.

Elphinston the Collector does indeed turn out to be the man shown as a boy in the portrait, painted in Edinburgh 35 years earlier in about 1812. Coming from much humbler stock Gibson was sadly not painted by Raeburn, and we have no record of his appearance at any stage of his life. When working on Gibson for my Dapuri book I had wondered if Elphinston, whose name was inconsistently spelt, might have been related to two Governors of Bombay, Mountstuart Elphinstone or his nephew John, Lord Elphinstone. The Raeburn catalogue, and some further Googling, showed otherwise – Alexander Elphinston was not of the family that held a Stirlingshire barony, but one with an Aberdeenshire baronetcy (if then under attainder), ‘of Glack’, near Inverurie. He was named for his grandfather, an Edinburgh advocate, whose only son John became a senior Bombay civil servant. John married and had a family in India and on his death in 1835 the young Alexander became the de jure 8th Baronet of Glack. From Bombay Alexander and his siblings Maria and Jane were sent ‘home’ to Edinburgh for schooling, to the care of their paternal aunt Jane (Jean), wife of John McKenzie of Applecross. The boy was in William Ritchie’s class at the Royal High School for three academic years from 1811 to 1814 (Robert Wight had left Ritchie for the Rector’s class in the first of these) and it must have been during this period that Raeburn painted the portrait. Two of his much younger siblings were not so fortunate and perished on the ship Alexander off Weymouth, en route from Bombay in 1815. Their distraught father sent instructions that the small bodies be taken north to lie in the family vault. This is adjacent to the gate of St Cuthbert’s kirkyard, unthinkingly walked over by thousands of pedestrians every day, including anyone heading south along Lothian Road to the Saturday Farmer’s Market or to a concert in the Usher Hall. Rather surprisingly for Aberdeenshire gentry the Elphinstons must have been Presbyterian, but the McKenzies were Episcopalians and Alexander’s Aunt Jane lies with her husband next door, in the ‘dormitory’ at the east end of St John’s. Their address when the three Indian children stayed with them is unknown, but by 1818 they lived almost opposite, at 136 Princes Street, five doors down from another Aberdeenshire family, the Skenes of Rubislaw.

Given that at this period India was the ‘Cornchest of Scotland’, there must be numerous Indian links among Raeburn’s sitters, of which a study would prove illuminating. Of the sitters included in the 1997 exhibition only three appear to have such links: the studious-looking Patrick Moir, secretary to the Governor-General Lord Minto, and who died in Calcutta in 1810; the haughty-looking Captain David Birrell of the Bengal Cavalry and John Johnstone of Alva, a rapacious nabob who extorted a fortune from Bengal in the 1760s.

Raeburn’s magnificent portrait of another Scottish nabob, George Paterson, now in Dundee Museum, was not in the exhibition, but one showing three of his children is included in the Catalogue, as a text figure in connection with the Elphinston portrait. With his marriage to the Hon. Anne Gray, Paterson married into impoverished aristocracy and used his lucre to purchase a castle from the Earl of Strathmore, an ancestral home of his wife’s family, which he renamed Castle Huntly (now an open prison). When asked what he thought of his daughter’s marriage Lord Gray’s practical reply was: ‘Weel, she has the bluid and he has the fillings, so between them they will mak a guid puddin’. With the portrait of the Paterson Children (now at Polesden Lacey) comes another, if tenuous, Indian botanical link. The middle boy John (born in the same calendar year as his elder brother George), who cheekily steals an apple from his sister’s basket, would become brother-in-law of the Ceylon botanist Anna Maria Walker. He grew up to become captain of the Castle Huntly East Indiaman and married Jessey Patton from the other side of the Tay, one of Anna Maria’s younger sisters. (See Botanical collections of Colonel and Mrs Walker : Ceylon, 1830-1838)

Maura Flannery

Another great post, thank you!