The kirkyard at Fortingall in Perthshire has, for several centuries, been a magnet for tourists with an arboricultural bent – for the sake of its ancient yew. This relic is now represented by several individual trees of utterly unremarkable size, but which represent circumferential saplings from a veteran that once had a girth of fifty-two feet, with an age variously estimated at two or five thousand years.

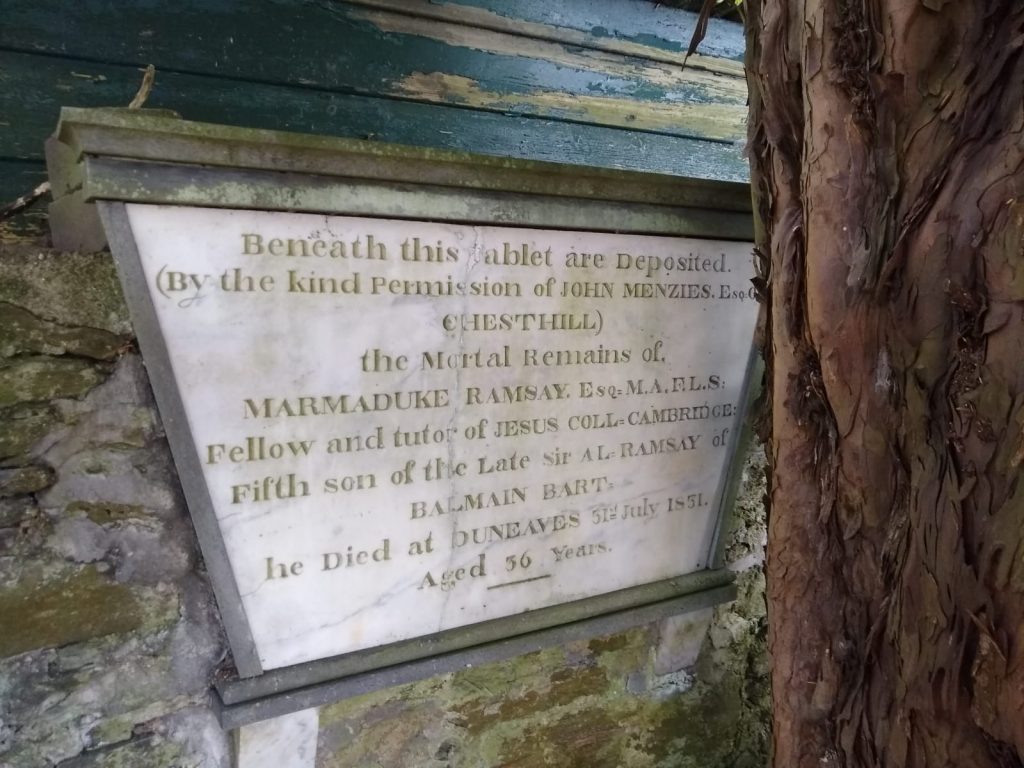

On a recent visit it was not the enclosure that protects these renowned trees that attracted my attention, rather an adjacent one – one of those in which Scottish lairds are traditionally laid to rest. It also housed another yew tree, perhaps an offspring of the ancient one, but it was an inscribed tablet on its wall that caught my eye. It commemorated ‘Marmaduke Ramsay MA FLS’ and it was the latter initials that intrigued me. Who was this man and what could have been the biological interests that led to his election to fellowship of the Linnean Society? The epitaph stated that Ramsay died at Duneaves (a small mansion close to Fortingall) on 31 July 1831, aged only 36, and that the enclosure belonged to John Menzies of Chesthill, a shooting lodge in nearby Glen Lyon. The fifth son of Sir Alexander Ramsay of Balmain, his occupation was given as Fellow and Tutor of Jesus College, Cambridge. This meant that he was a brother of the great Edward Bannerman Ramsay, Dean of Edinburgh, and incumbent of St John’s Princes Street, my local church, where there is a tablet to their mother the Dowager Lady Ramsay of Balmain. Dean Ramsay was author of the charming Reminiscences of Scottish Life and Character in which he records that ‘by an awful dispensation of God’s providence’ the death of that feisty botanist, Christian, Countess of Dalhousie (mother of the Governor-General), ‘happened instantaneously under my roof [11 Ainslie Place] in 1839’. A curious connection as at Kew only the previous week I had been cataloguing the drawings commissioned by Lady Dalhousie from a ‘native artist’ in Simla in 1831. As wife of the Commander-in-Chief of the Indian army she was in the then recently established hill station for seven months, and while there had botanical chit-chat and exchanged drawings with the founder of the Saharunpur Botanic Garden, George Govan and his similarly Scoto-botanophil-aristocratic wife Mary Maitland, whose collection of drawings I had also catalogued.

On my return home, thanks to Google and the somewhat large section of my bookshelves occupied by Darwinian biography, an intriguing story emerged. It turned out that, through Darwin’s mentor the Rev. J.S. Henslow, Marmaduke Ramsay had become a close friend of Darwin. While Lady Dalhousie was botanising in the Himalayas Darwin and Ramsay were planning a natural-historical adventure to Tenerife in the Canary Islands. Darwin was deeply affected by the news of Ramsay’s sudden and unexpected death in Perthshire. It was not only that it put paid to the Canary expedition but, especially when young, the loss of a near contemporary (he was only 14 years Darwin’s senior) must always seem particularly shocking. That life went on, and in fact was about vastly to expand, comes from the irony that it was in the same letter (in August 1831) that Henslow told Darwin of Ramsay’s death that he raised the possibility of his young protégé’s participation in the Beagle voyage. The rest, as they say, is history …

I have yet to discover the reasons for Ramsay’s election to the Linnean Society, and Darwin appears to have rated Ramsay more for his personality (‘a delightful man’) than as a naturalist (who did ‘not care much about science’). Only one source throws any light on this: in their book on Darwin and slavery Desmond and Moore state, but with no supporting reference, that Ramsay ‘shared the age’s craze for ferns’. But the touching thing is to have stumbled unexpectedly, in a highland graveyard, on a memorial that revealed a historic and significant friendship with the author of On the Origin of Species.