By Henry Noltie

In April 2017 I visited a memorable exhibition at the Yale Center for British Art at New Haven, CT. It was entitled ‘Enlightened Princesses’ and explored the lives of three Hanoverian spouses and their patronage. Taken in conjunction with an excellent TV series by Lucy Worsley broadcast around the same time, it comprehensively exploded any nasty British suspicions of the Hanoverian dynasty as one of uncultured philistines. The three princesses were Caroline of Ansbach (1683–1737) who married George II, Augusta of Saxe-Gotha (1719–1772), founder of Kew and wife of Frederick Prince of Wales, and Charlotte of Mecklenberg-Strelitz (1744–1818), Augusta’s daughter-in-law and wife of George III.

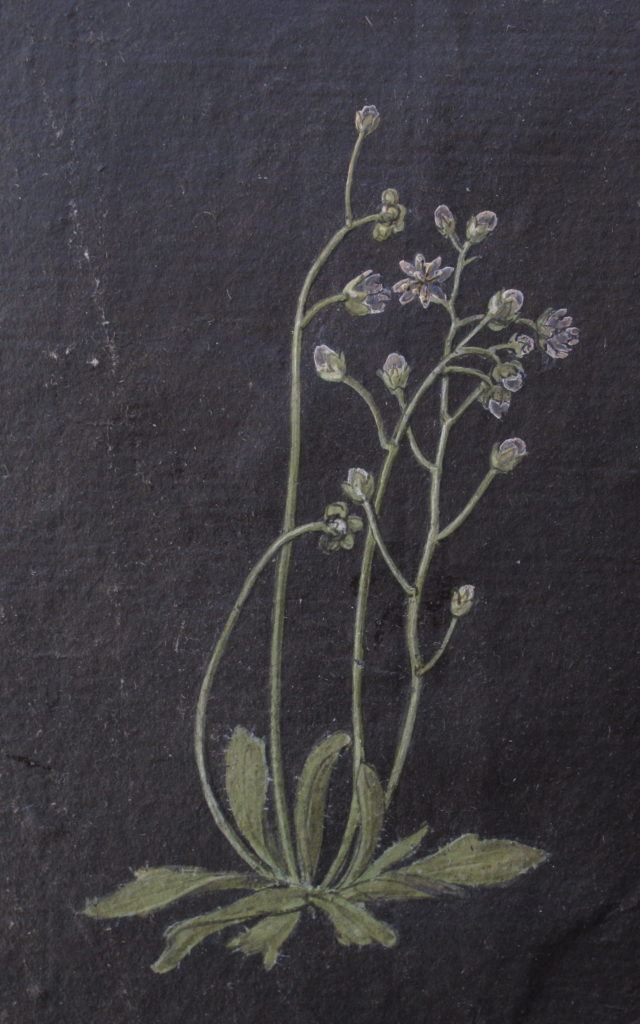

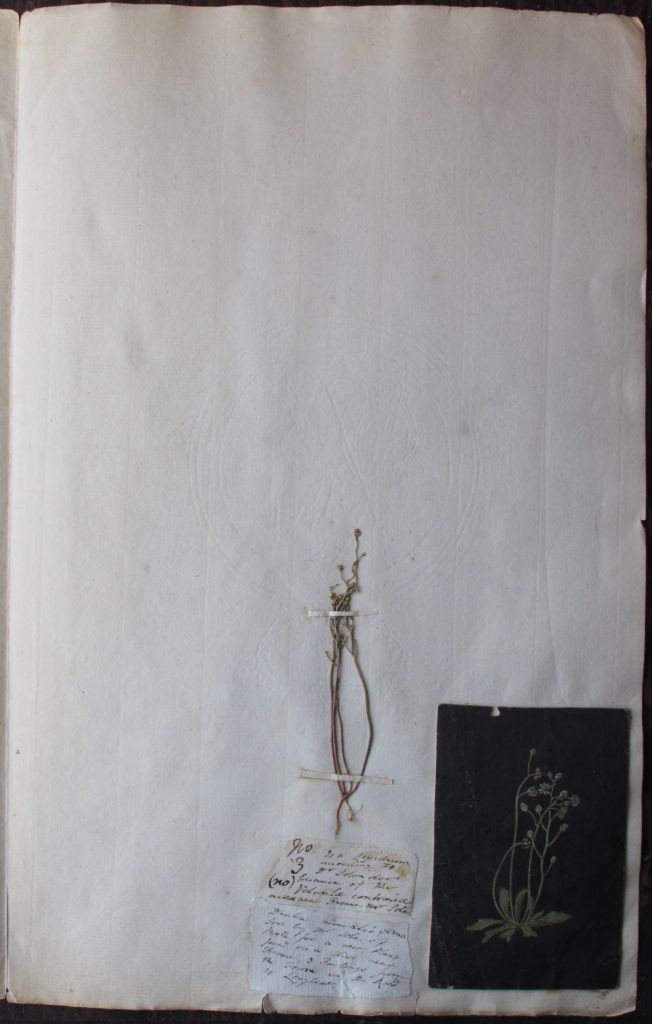

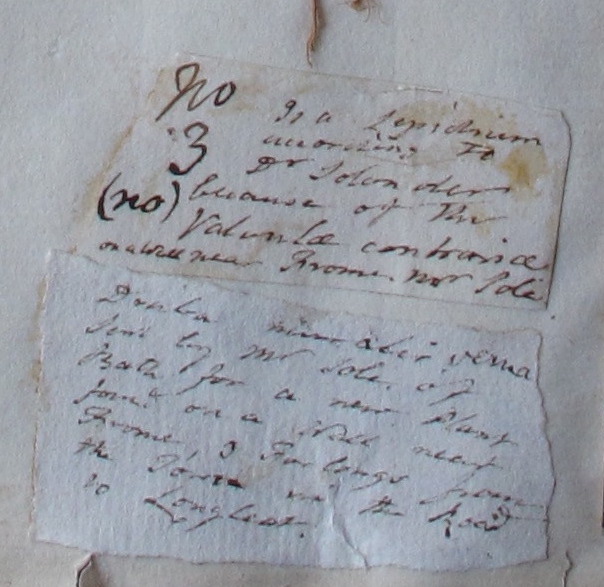

In the botanical section, in a display case, were two specimen-folders from the herbarium of the Rev John Lightfoot (1735–1788), author of Flora Scotica, and chaplain-naturalist to the Duchess of Portland. In 1788, following the cleric-naturalist’s death his herbarium had been purchased for a hundred guineas by George III as a gift for his wife. One of the sheets bore the shrivelled remnants of a small cruciferous plant accompanied by two hand-written tickets and a tiny, coloured image on a rectangle of black paper. The exhibit’s label caught my pedantic eye, initially for the plant name ‘Lepidium’ taken uncritically from one of the tickets, though the other did bear what was in Lightfoot’s day the plant’s correct name Draba verna (now Erophila verna). But also because the label claimed that the image was a ‘collage of coloured papers’.

The glorious botanical paper mosaics of Mary Delany (1700–1788), almost a thousand in number made between the ages of 72 and 82, are well known. Because of Mrs Delany’s friendship with Queen Charlotte several of her ‘mosaics’ on black backgrounds were included in the exhibition, and it would have been perfectly possible for such a work, either by Mrs Delany (a friend of Lightfoot), or one of the Royal princesses (to whom she taught her technique between 1786 and 1788), to have been added to the herbarium sheet. However, even through the glass of the vitrine, it did not – either from its texture or its diminutive size – look like a mosaic. The coloured, life-size image was only 3.5 centimetres high and the flowering scapes only half a millimetre in width – surely impossible to have been cut from painted paper by scalpel or scissors even wielded by the deftest of hands and sharpest eyes. The exhibition was about to travel on for a second showing at Kensington Palace, so it wasn’t until a year later that I was able to study the sheet following its return to its Kew home.

The image is discussed in several chapters of the excellent exhibition catalogue, though in a confusing, not to say contradictory, manner. Mark Laird referred to it as a ‘Delany-style collage’, and speculated as to whether the ‘unique work’ was made at Bulstrode (the Buckinghamshire home of the Duchess of Portland) ‘under the eyes of Delany and John Lightfoot’, or if it might have been added to the sheet ‘after Delany’s death in 1788, as a royal tribute to her genre of botanical collage?’ In fact Laird himself unwittingly alluded to the true nature of the image with a reference to Queen Charlotte’s botanical interests, which he found in Ray Desmond’s history of Kew.

On 19 March 1788 the Queen wrote to her late mother-in-law’s botanical advisor, Lord Bute, about a ‘Herbal from impressions on black paper’ that she was then making. Both Laird and Desmond mistook this to mean the mounting of real specimens. In fact the Queen’s letter, as hinted at in Todd Longstaffe-Gowan’s catalogue chapter, refers to a technique taught to the Queen and the three princesses, Charlotte (the Princess Royal), Augusta Sophia and Elizabeth, at Frogmore, Windsor, by a Mr and Mrs Lock of Norbury. Plants from the royal gardens were pressed into soft black paper and the impressions then painted using fine brushes.

Further details are to be found in Lorna Clark’s 2014 edition of Fanny Burney’s Court Journals and Letters for the year 1788. The Queen had what Fanny (then a Keeper of the Robes) described as a ‘violent hankering’ for the ‘colouring of plants’, in which she had been instructed by William Lock, described as the ‘Norbury pastime of pressing live plants (a skill at which his wife excelled) and then painting the impressions’. On 30 March 1788 Fanny wrote to her father, the musical historian Dr Charles Burney: ‘We go on prodigiously well here [Windsor]. Mr Lock gives almost Daily lessons, in Colouring the Plants, & with great success, – not only with his first [the Queen], but with three younger Royal Pupils [the princesses]: & Mrs Lock has been called upon to Lesson in the Impression taking’.

The Locks of Norbury

William Lock (1732–1810) and his wife Frederica (‘Freddy’) née Schaub (1750–1832) were a wealthy and cultured couple, friends of Fanny Burney and of Mrs Delany, who were presented to the Royal family in 1787. Lock had inherited a fortune from his father, a London merchant and MP, but lived a life of leisure, which began with an artistic Grand Tour before establishing himself and his beautiful wife in various grand houses in Mayfair and a mansion at Norbury near Box Hill in Surrey, which he had built to designs by Thomas Sandby. The estate was an old one with an astonishing number of walnut trees, the wood of which was used for making gun-stocks.

The main drawing room of the new house was an spectacular ‘Panoramic Room’, its ceiling and walls entirely covered with murals with landscapes by the Irish artist George Barret, with additional details by Sawrey Gilpin and Giovanni Battista Cipriani (Barret had earlier worked in Scotland, painting three landscapes of the park at Dalkeith for the Duke of Buccleuch, as recently described by John Bonehill). The Norbury house (which from 1938 to 1958 it was owned by Marie Stopes) has had a chequered history, though the murals survive if in diminished condition.

Lock was a close friend of John Julius Angerstein, founder of the National Gallery, and one of his daughters, Amelia, married Angerstein’s son John. Lock’s eldest son, also William, an artist, married and left descendants including a glamorous great great grand-daughter Vittoria Colonna Caetani, Duchessa di Sermoneta. It is from the duchess’s fascinating 1940 biography of the family that more is learnt, even if she was rather lofty about her forbear’s plant impressions, which, while admiring of William’s expertise, she considered a ‘pretty and useless art’. Frederica continued to make impressions in her widowhood, of which many apparently survived in albums at Holbrook in Somerset until this was sold in 1945 on the death of Georgina Angerstein (widow of Amelia Lock’s grandson). The survival or whereabouts of these albums, as with Queen Charlotte’s ‘Herbal’ of impressions, is unknown. They may lurk unidentified in some library or collection, but would be easily recognised from their black backgrounds; their rediscovery would throw light on this scarcely-known technique of eighteenth-century botanical illustration.

Lightfoot, Smith and the Royal Family

The interest of the royal ladies in botany and art was considerable and, as described by Jane Roberts, Princess Elizabeth, in particular, became a skilled botanical painter and probably a Delany-style mosaicist. In 1791 James Edward Smith was asked to curate the Lightfoot herbarium for the Queen, which the Bishop of Carlisle, Samuel Goodenough, had found to require attention. In February 1792 Smith attended Frogmore for the first time and not only attended to the herbarium but gave ‘conversations’ on botany and natural history to the Queen and the princesses. Several more sessions took place and Smith took notes from the herbarium for use in his Flora Britannica

The interaction came to a sticky end when the Queen took offence at passages in Smith’s 1793 Sketch of a Tour on the Continent, in the years 1786 and 1787 that had been drawn to her attention. Smith’s defence of Rousseau and his comparison of Marie Antoinette to the Empress Messalina made Smith appear more radical than he really was, but the royal lessons came to an abrupt halt. In 1821, two years after Queen Charlotte’s death, many of her possessions were secretly sold by her rakish son George IV to pay for his gambling debts. Lightfoot’s herbarium was purchased by Robert Brown for 50 guineas, but at some stage in the 1850s Brown must have parted with it. After a mysterious spell in a museum in Saffron Walden, at least the majority of it was acquired by Kew in 1921, where it remains, kept in its own cabinets on the stairs of Hunter House.

The Lightfoot sheet and the painting

In April 2018 I was able to examine the Lightfoot specimen. The sheets are folios folded in half so as to protect the specimen mounted on the right hand side of the sheet. On the one in question is a single specimen of the diminutive annual Erophila verna collected considerably after its prime. It was sent to Lightfoot by the Bath botanist William Sole (1741–1802), who thought it to be a ‘new plant’, from a ‘wall near Frome, 3 Furlongs from the Town on the Road to Longleat’. On the ticket with the collecting details the name Draba muralis was initially written, with the (correct) epithet ‘verna’ apparently added slightly later – it is the second ticket that bears the incorrect identification of ‘Lepidium’, which had been given by Daniel Solander on account, as he thought, of the plant’s ‘Valvulae contrariae’.

The painting itself is in gouache, with some tiny losses where the thick paint has ‘pinged’ off. It shows a close attention to detail, with minute hairs added to the margins of the leaves. Presumably the paint was applied to the impressed surface of the paper, but the thickness of the gouache conceals this, and the slightly raised surface of the scapes and the anthers of the single open flower are due to the body of the paint. The impression must initially have been emphasised, as there are also traces of pencil outlining the image that must have been added before the paint, and after this there has been some over-drawing with ink to define the sepals, petals and filaments.

The question of who made the drawing, and when, must remain open, but the strong likelihood is that it was made in March 1788, at the time that the Locks were instructing the royal ladies. This corresponds with the time when Erophila would have been flowering – perhaps as a weed on a garden path at Frogmore. It is possible that it is by Queen Charlotte herself, but one of the Princesses is perhaps the more likely, especially Princess Elizabeth (1770–1840), who is known to have been the most skilful artist.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Sally Dawson of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew for access to the Lightfoot herbarium and Tom Kennett for information on James Edward Smith.

References

Bonehill, J. (2021). Scotland’s prospects. In Old Ways, New Roads; travels in Scotland 1726–1832, J. Bonehill, A. Dulau Beveridge & N. Leask (eds), (pp 126–45). Edinburgh: Birlinn.

Clark, L.J. (ed) (2014). The Court Journals & Letters of Frances Burney. Volume III, 1788 (pp 190–1). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Desmond, R. (1995). Kew: the History of the Royal Botanic Gardens (p 79). London: Harvill Press and RBG Kew.

Kennett, T. (2016). The Lord Treasurer of Botany: Sir James Edward Smith and the Linnaean Collections. London: Linnean Society of London.

Laird, M. (2017). An august domain: gardening and collecting in the Princesses’ Kew. In Enlightened Princesses: Caroline, Augusta, Charlotte, and the shaping of the modern world, pp 133–59 (ed. J. Marschner). New Haven & London, Yale Center for British Art.

Longstaffe-Gowan, T. (2017). Hankering after horticulture. In Enlightened Princesses: Caroline, Augusta, Charlotte, and the shaping of the modern world, pp 349–57 (ed. J. Marschner). New Haven & London, Yale Center for British Art.

Pain & Stewart (2014). Norbury Park House: survey of the painted decoration in the Panoramic Room. https://www.molevalley.gov.uk/CausewayDocList/DocServlet?ref=MO/2015/0433&docid=559965 consulted 20 iii 2021.

Roberts, J. (2017). Frogmore and the Princesses as artists. In Enlightened Princesses: Caroline, Augusta, Charlotte, and the shaping of the modern world, pp 375–83 (ed. J. Marschner). New Haven & London, Yale Center for British Art.

Sermoneta, Duchess of (1940). The Locks of Norbury: the study of a remarkable family in the XVIIIth and XIXth centuries (pp 27, 280). London: John Murray.

1 Comment

1 Pingback