What is the ‘mushroomy’ scent of heritage? And what do the institutions that care for it — such as the RBGE — smell like?

By Siôn Parkinson

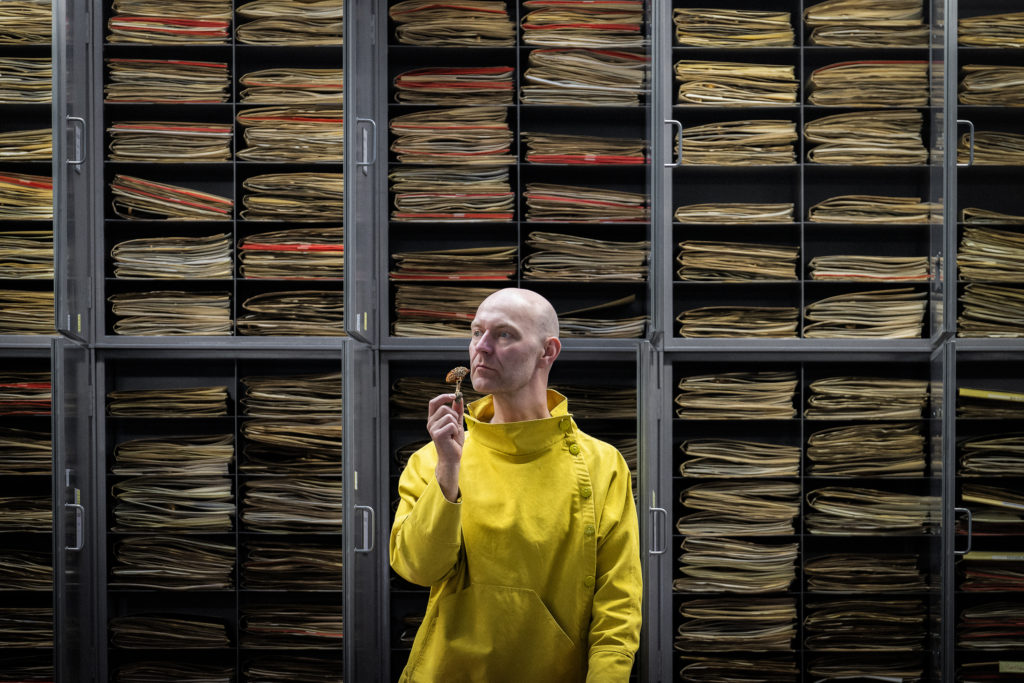

Dr Siôn Parkinson, artist and AHRC Research Fellow, in the RBGE Herbarium. Image: RBGE, 2024.

1 ~ In January 2024, I joined the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh as a Research Fellow as part of a pilot scheme funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC). The fellowship, which has been awarded to eight postdoctoral researchers in the UK, is designed to encourage early career researchers — such as artists like me — to embed their research within cultural and heritage institutions like the RBGE. The aim of my project, which is titled ‘Fragrance in the Fungarium’, is to offer insights into the olfactory heritage of mushrooms — fungal odours that are culturally or historically significant. Over the next two years, I’ll be collaborating with librarians, archivists, conservators, gallery and herbarium curators, horticulturalists and scientists to identify meaningful mushroom smells in various collections and spaces at the RBGE. Once I’ve established which smells to focus on, my aim is to test creative ways of capturing and communicating them to audiences and other specialists working in the heritage sector. In other words, my job is ‘Sniffer in Residence’.

1.1 ~ On any given day, you might find me sniffing about aisles of old mycological books, artefacts and artworks in the Library, poking my nose into cabinets of preserved mushroom specimens in the Herbarium, or following a fungal scent out in the Garden. To ‘sniff about’ means to investigate something with curiosity. The phrase carries with it a connotation of inquisitiveness, of trying to understand something intuitively, yet not without some degree of conscious reasoning. More literally, it means to prioritise the nose over one’s other sense organs and to use smelling as a means of exploring an area or object.

1.11 ~ So, what exactly does the RBGE smell like? And what can a Sniffer in Residence reveal about our broader relationship with fungi through the act of smelling? Extending this thought experiment a little further, we might ask: What is the smell of heritage, and the institutions that care for it? Perhaps this question gets us closer to what an independent research organisation like the RBGE does, rather than what it is (which, in one obvious interpretation, encompasses the buildings, people, structures and histories that have helped constitute it).

Old books, old plants

1.2 ~ Smell marks the trace of human and more-than-human activity, signifying something happening now, having just happened, or having happened hundreds, if not thousands, of years ago. And this trace is perceptible in the air, emanating from the various spaces, specimens and artefacts housed within the institution.

1.21 ~ Something my colleague said to me on my first day while being given a tour of the science buildings helps illustrates this sentiment. Pausing in the basement just outside the Rare Books Room — a compact four-by-four-metre storage unit that contains any book in the RBGE collection published before 1850 — Lorna Mitchell, Head of Library and Archives, explained to me the following: ‘The average length of time an individual has been employed at the RBG is about fifteen years. If you’ve worked here for that amount of time, it’s easy to imagine finding your way around the buildings blindfold, guided by smells alone. […] The Rare Books Room has a very particular smell, for example, which is different from the Library, which is yet again different from the Herbarium.’

1.211 ~ ‘So, what is the smell of the Rare Books Room?’ I asked, to which Lorna replied naturally, ‘It just smells like the Rare Books Room.’ When I later posed this question to Heleen Plaisier, Assistant Curator of the Herbarium, asking ‘What is the smell of the Herbarium?’ the answer that came back was similarly reflexive and tautological: ‘It smells like the Herbarium.’

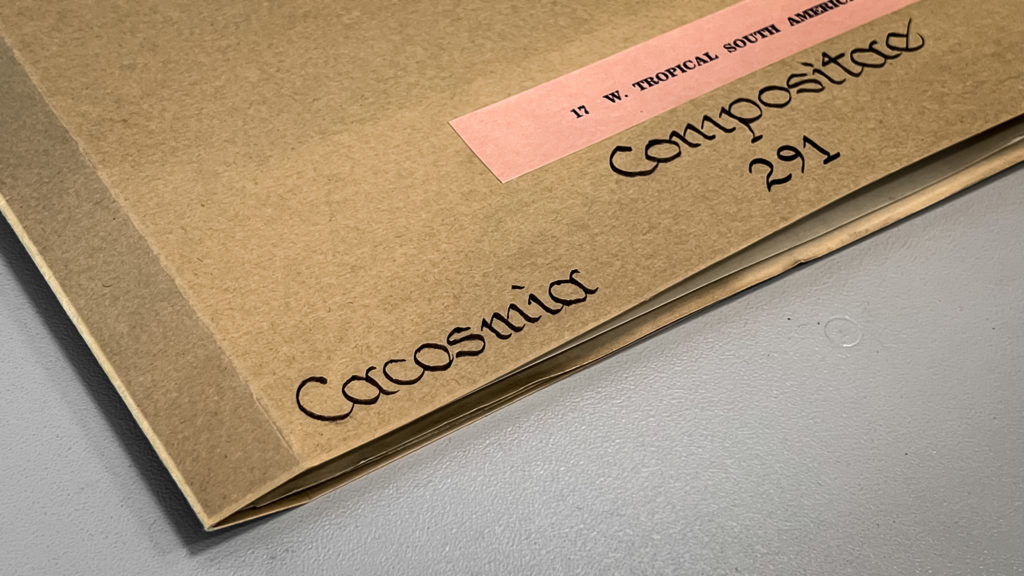

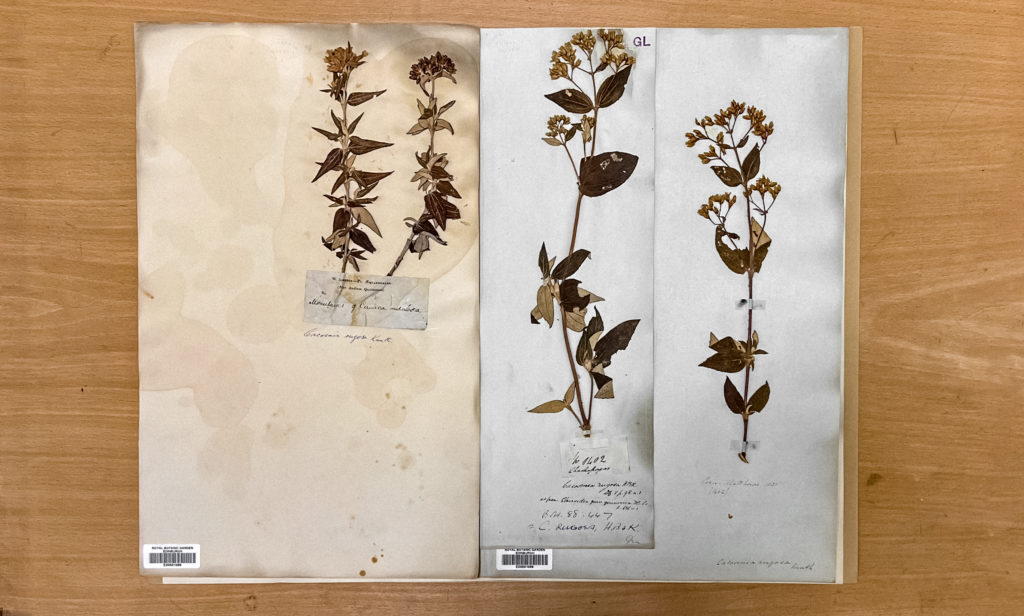

Herbarium folder containing specimens of the ‘foul-smelling’ Cacosmia rugosa — which this author believes smell like plimsolls. Image: Siôn Parkinson, 2024.

1.22 ~ Neither Lorna nor Heleen were being facile or unimaginative in their description of smell. Rather, they were simply expressing their knowledge of specific smellscapes that, over time, have become so deeply familiar and embodied that the thing and the smell of the thing have become synonymous. Thus, the Rare Books Room smells like the Rare Books Room, and the Herbarium smells like the Herbarium.

1.23 ~ In my two-year tenure as Research Fellow/Sniffer in Residence, I have the opportunity to approach this question — what does an institution smell like? — with a fresh perspective, and with a nose as-yet unburdened by institutional longueurs. As such, and after only a few months under my belt, I can confidently report the following: The Rare Books Room smells of old books. And the Herbarium smells of old plant matter.

1.231 ~ Hardly surprising. But after spending a little more time in each space, I’d like to refine the above to say that the Rare Books Room smells intensely strong and sour, a blend of bitter chocolate, tanned leather shoes, second-hand textiles, and the dusty melange of a kitchen spice drawer. The Herbarium, on the other hand, evokes the nostalgic scent of a 1980s primary school classroom: a blend of PVA glue, pencil wood shavings, and faint tracings of rancid cooking oil. This aroma is enhanced by the pervasive presence of linoleum, which in various coloured marble effects covers nearly every horizontal surface, from the floors to the workbenches.

1.232 ~ There is a faintly woody, resinous ambience throughout, a scent subdued by the long stretches of grey, powder-coated cabinet doors, which house the RBGE’s three million plant and fungus specimens across two floors and over a thousand cabinets. More aromas are articulated as you progress down the corridors and begin to open individual cabinets and pull folders from their shelves. For example, the smell of one cabinet containing a few specimens of the flowering plant Cacosmia rugosa (which literally translates as ‘foul-smelling’ and ‘wrinkled’) is reminiscent of brand-new plimsolls. Another cabinet, containing specimens of Zanthoxylum armatum and Zanthoxylum bungeanum (from which Sichuan pepper spice is derived), exudes a gorgeously sweet, citrusy, smoky and aromatic scent, similar to a mescal cocktail with orange bitters. These are just a couple of examples of the potentially thousands of smell combinations waiting to be discovered behind each door.

Mushroomy

1.3 ~ However, my focus is on fungi. The smell of the fungi collection is savoury, beery, honeyed, uric, yeasty — of gym shorts and jock rash. But mostly, as Heleen succinctly describes it, it ‘smells mushroomy’. Sniffing inside a few cabinets at the end of the first of two aisles containing specimens of British Basidiomycetes reveals a mushroomy smell that is overwhelming. Upon opening the door to the Boletes, a cabinet which contains bulging, pillow-like folders of Boletus edulis — more commonly known as porcini or ceps — the scent is so strong as to be intoxicating. Perhaps it’s because of the age of the specimens, which have matured and deepened over time (the oldest is dated to 1967 making it about 57 years old), that they have tipped over from strongly savoury to sour and nauseating.

Festive postcard of a winter scene featuring a pig sniffing an over-sized fly agaric Amantia muscaria (Tallinn, Estonia, c.1950s).

1.31 ~ However, the Amanitas, which are stored nearby, are by far the worst. This cabinet houses specimens such as Amanita muscaria — the famous fly agaric popularised by Super Mario Bros. and children’s book illustrations everywhere — and the deadly poisonous destroying angel (Amanita virosa). Even a whiff of the outside of the folder reveals a sickly-sweet fragrance inside of overripe honey, train toilets and wet dog.

Biting smells

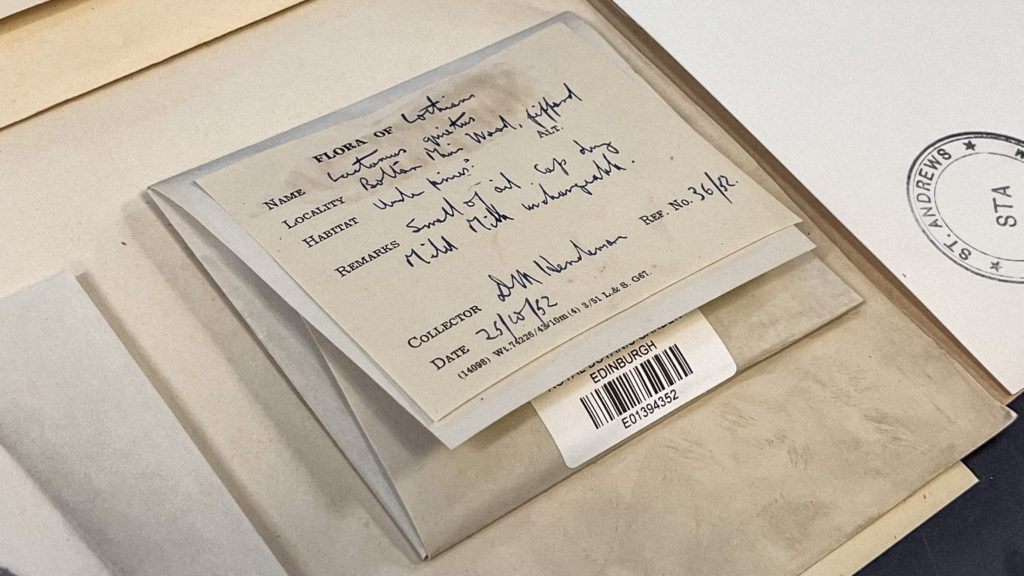

1.4 ~ As you browse the fungi collection, occasionally you’ll find a description of a fungal odour written on the herbarium sheet label, which is included as part of the specimen catalogue data. For example, the label to a collection of fenugreek milkcaps (Lactarius helvus) from 1955 bears the hand-written remark ‘Smell mild at first, then of fenugreek’. This odour of fenugreek — which, to be specific, smells to me more like fenugreek leaves — strongly persists nearly seventy years later.

1.41 ~ On another label for a specimen identified as Lactarius quietus, collected in 1952 by mycologist and former RBGE Regius Keeper (1970-1987) Douglas Mackay Henderson, it says ‘Smell of oil’. Along with this oily odour, it’s often repeated in mushroom identification books that Lactarius quietus smells of bedbugs, hence its common name: oakbug milkcap.

Fenugreek milkcaps (Lactarius helvus), collected 1955. Image: Siôn Parkinson, 2024.

1.411 ~ A quick aside: The Latin species epithet of the oakbug milkcap — quietus — means ‘at rest’. Might we interpret the scientific name of this odorous milkcap as an ironic description of the smell of sleep? For Elias Fries, the Swedish mycologist who first named Lactarius quietus in 1838, maybe the sickly-sweet scent of this otherwise unremarkable mushroom reminded him of the horrors of bedtime. Just maybe its odour recalled the comforting vapours of warm milk mixed with the nauseating stench of stinkbug secretions that confronted the unfortunate mycologist every evening as he climbed bravely between the bedclothes to offer up his flesh. Lactarius quietus: the foreboding, formicating smell that follows a milky calm.

Preserved specimens of the oakbug milkcap (Lactarius quietus), dated 1952. The hand-written remark on the label says ‘Smell of oil’. Image: Siôn Parkinson, 2024.

1.42 ~ Elsewhere, the smell of bedbugs has been described as reminiscent of coriander — or, to be more specific, the smell of the plant’s unripe seeds when crushed [1]. In a book published in English in 1745, French botanist Louis Lémery reverses this association, describing coriander as having an ‘unpleasant Smell, like that of Buggs’ (in Britain from the early seventeenth and way into the middle of the twentieth century, bedbugs were simply referred to as ‘bugs’) [2]. The word coriander actually derives from the smell of bedbugs, and not the other way round, formed from the ancient Greek word koris meaning ‘to bite’ [3]. The Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder called the plant coriandrum (from which the genus name derives) due to its having a foetid odour reminiscent of bedbugs [4].

1.43 ~ Clearly the stench of bedbugs was a much more common olfactory experience in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries than it is today. Though this is changing — and fast. In the last few decades, bedbug infestations in homes across Europe are reported to be rising dramatically, notably in Paris where one in ten city-dwellers were said to have encountered bedbugs in the last five years [5]. It seems highly likely we’ll become reacquainted with this old smell sometime soon.

Sniff this space

1.5 ~ So, what is the smell of bedbugs, you might wonder? Do they really smell oily or like crushed coriander seeds? Well, sniff a fresh oakbug milkcap and you can soon find out. Mushrooms are sensory portals, allowing us to travel back in time to encounter past smells. Which begs the question: What other heritage odours, imbued in the fungi specimens within the cabinets and corridors of the Herbarium, are still quietly waiting to be discovered? And where, and when, might they take us next?

1.51 ~ These are just some of the questions I hope to answer during my time as Sniffer in Residence at the RBGE. I’m only getting started, but I already have lots to share, which I plan to do here and often. So, watch (sniff?) this space.

Notes

[1] Michael F. Potter, ‘The History of Bed Bug Management — With Lessons from the Past’, American Entomologist 57, 1 (2011), pp. 14-32 (15).

[2] Louis Lémery, A Treatise of All Sorts of Foods, Both Animal and Vegetable; also of Drinkables: Giving an Account how to chuse the best Sort of all Kinds (London: T. Osborne, 1745), 157.

[3] Potter, ‘History of Bed Bug Management’, p. 15.

[4] Pliny the Elder, The Natural History, trans. John Bostock (London: Taylor and Francis, 1855), book 20, chapter 82.

[5] Hugh Schofield, ‘Bedbug panic sweeps Paris as infestations soar before 2024 Olympics’, BBC News, October 3, 2023, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-66995977.