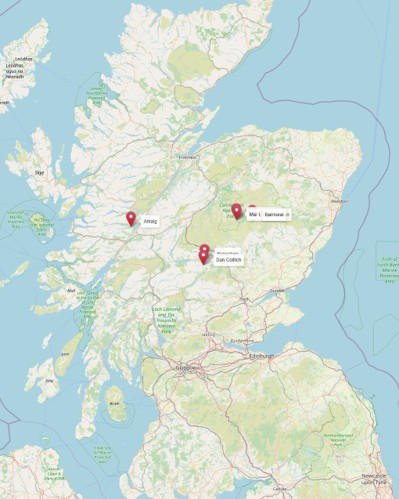

In the months of October and November 2025, the NRF Scottish Plant Recovery team carried out a series of translocations which challenged us logistically, mentally and physically and which required a lot of planning and organisation to make sure it all ran out as smoothly as possible. As the winter was drawing in, we were under a time restraint to get everything planted out before any frosts. Therefore, we decided to tackle the task of planting out 3 of the species in the Scottish Plant Recovery Project at the same time across different parts of the country. The 3 species naturally inhabit similar riparian woodland habitats meaning that at certain sites, such as Dun Coillich, we were able to plant out all 3 species in one day at the same site. Over the space of 4 weeks our team translocated:

- 500 Whorled Solomons seal (Polygonatum verticillatum) plants across 5 sites.

- 34,000 Small cow-wheat (Melampyrum sylvaticum) seeds across 12 sites.

- 200 Alpine blue sow thistle (Cicerbita alpina) seedlings across 2 sites.

A colour coded system was put into place, with every species and site being assigned a different colour so we could identify what was going where once everything was in the van.

My intention in this Scottish Plant Recovery story is to highlight the different details and methods for these series of translocations of each of these 3 riparian native species.

Melampyrum sylvaticum

In comparison to our previous tree planting efforts, our M. sylvaticum translocation was probably one of our most straight forward translocations in the field so far. The only annual species on our project, the small cow wheat (Melampyrum sylvaticum) has been threatened across Scotland due to major habitat loss attributed to afforestation, over extensive use of fertiliser at woodland edges and both grazing and trampling caused by livestock. What populations remain in Scotland is a concerning picture, with only 10-15 natural remaining populations left, the genetic diversity of M. sylvaticum is worryingly low.

At the RBGE Nursery an unplanned series of events presented us with a solution to bolster the genetics of Scotland’s M. sylvaticum population. After the results from our garden trial, we had collected seed from some of the remaining Scottish native populations and sown them in Sorbus aucuparia pots. However, we did not have the foresight to isolate the different populations from each other, allowing open cross pollination. As a result, we ended up creating what we’ve coined our “Scottish Supermix” as it has shown to be significantly more resilient and genetically diverse than the individual provenances. Our Supermix has been used in most of our translocations across the country.

As previously described in this Botanic stories article, there is an existing theory that M. sylvaticum’s decline has also been caused by a lack of natural seed dispersers, in particular that of the wood ant which is also threatened in Scotland. To put this theory to the test, we carried out translocations at 12 different sites across Scotland, 5 of which were in close proximity to a wood ants nest.

Red, No wood ants.

Black, wood ants present.

This will hopefully allow us to finally gain a better understanding of how M. sylvaticum disperses its seed and whether the absence of the wood ant was the missing piece of the puzzle which was causing its rapid decline.

As we wanted to keep this trial as consistent as possible, we had equally prepared bags of 200 M. sylvaticum seed at the nursery and had everything labelled to make it as easy as possible in the field. The total number of translocated mixed provenance seed amounted to around 34,000!

To keep a track of the seed dispersal of M. sylvaticum, our Horticultural Project lead, Rebecca Drew, came up with the fabulous hula hoop technique. Essentially a more fun take on a quadrat (with the added bonus of practising your hula hooping in between translocations) we would place a hoop at every labelled stake. We then gently pulled back some of the vegetation within the hoop and simply sprinkled in our Supermix. Taking a photo of the hoop once the seed was sown allowed us to have a baseline for monitoring. We plan to go back to every site next year with our hula hoops, place them back at each stake once the seed has germinated and monitor the success rate of our translocations as well as checking the spread of dispersal within the hoop and hopefully even outside the hoop.

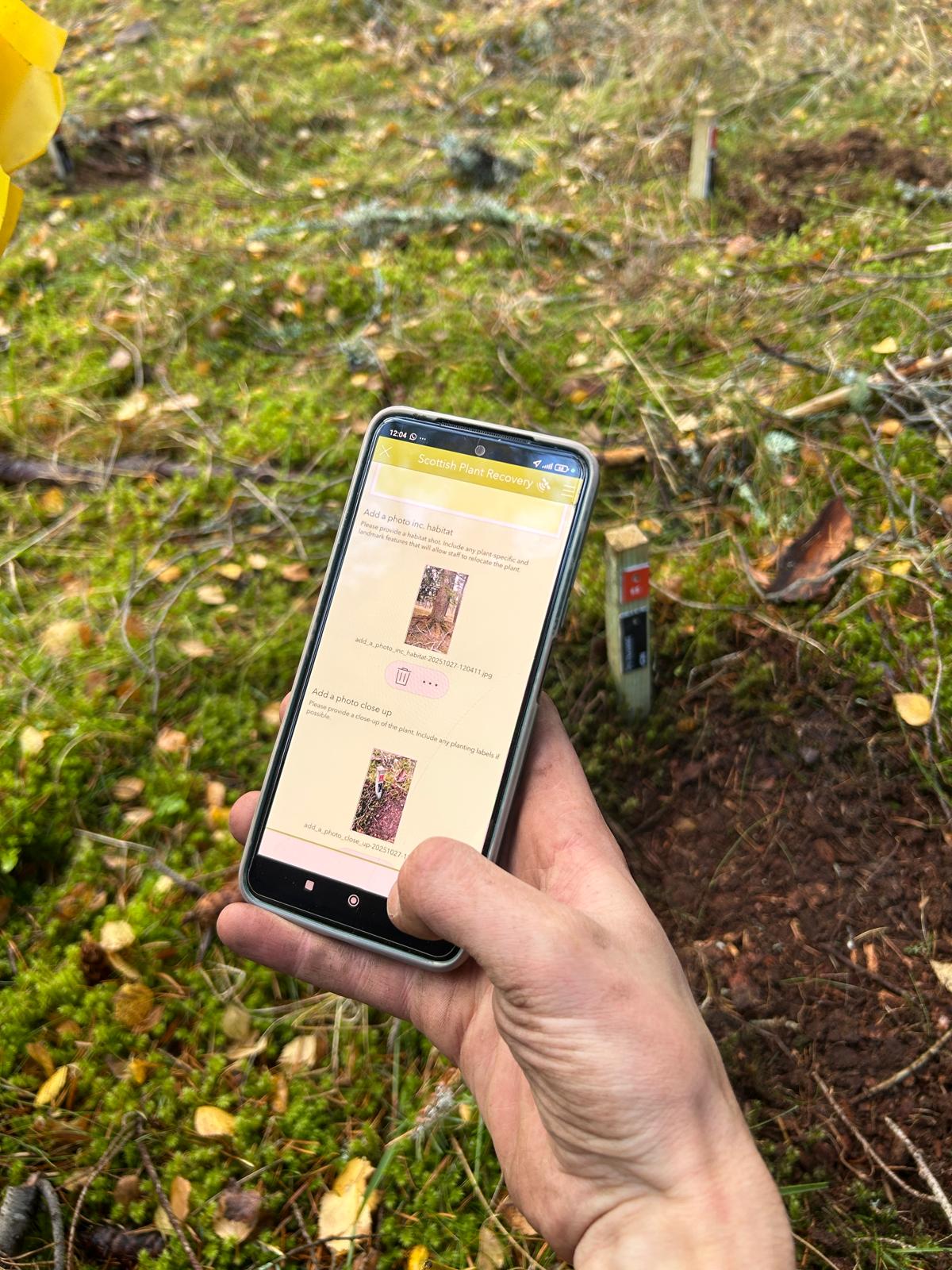

Throughout all of the species on the Scottish Plant Recovery Project, we have been using ArcGIS Survey123 to monitor our translocations. This is a mobile app which has a super accessible user-friendly interface and allows the surveyor to take photos, GPS coordinates and note down any important information on the specimens. Aswell as monitoring the success of our translocations, we are also interested in the different environmental variables across our site and to what extent this could have an effect on translocation success. Therefore, 3 TinyTag data loggers which measure both the relative humidity and temperature every day for over a year were also placed at each site.

Cicerbita alpina

Although we had carried out the majority of the translocations for C. alpina in both 2023 and 2024, we were lucky to receive some extra funding which meant we were able to add another 200 C. alpina seedlings out into the Scottish landscape. The translocations at Kynachan and Dun Coillich has meant that we have now planted 1200 mixed provenances of C. alpina in 6 sites across the country.

Over the summer, our team conducted some monitoring of our previous translocations, and we were really pleased to record an 80% survival rate from our translocated specimens of C. alpina. I think the combination of mixed genetics, planting into land which is either fenced or heavily stalked by landowners, as well as having cages to protect the plants from grazing, has given the plants a good chance to establish themselves.

Unfortunately, sometimes things just don’t go to plan, no matter how prepared one is, nature will throw some challenges at you and with a rapidly changing climate these challenges will become more frequent. For our translocated plants, which already have enough challenges to face, we want to ensure that we have ways of identifying any losses when things go wrong. When we arrived at Balmoral to plant out both P. verticillatum and M. sylvaticum we found that there had been damage to our previous C.alpina site due to the high winds during Storm Eowyn that had caused a tree to fall over right on our translocated specimens! This highlighted to us once again the importance of ensuring that every plant is labelled and GPS tracked so that we can have high traceability of all our translocations. Knowing where the plant is or at least where it was means that we can replace those that are lost, update our records and ensure the population numbers stay healthy.

Polygonatum verticillatum

After the results from our mini trial which proved that the cause for P. verticillatums sudden dieback at the RBGE nursery each year was in fact cultural instead of viral, we had the go ahead to carry out our 5 planned translocations across Scotland. As P. verticillatum suffers from very low genetic diversity we equally spread out our different provenances in our collections across our translocations to bolster the genetic diversity of these new populations. The preparation at the RBGE nursery for P. verticillatum involved removing as much soil as possible from the rhizomes without damaging them. For biosecurity concerns, we want to minimise as much media that goes out with the plants as possible but also want to make sure we are translocating healthy plants so finding the balance when packing them is important.

Across our translocations we also planted out 3 stages of life: rhizomes from established mature plants, seedlings and direct sowing of seed. Planting out the 3 stages of life can hopefully give us an indication on the success of suitability for each site. If a site can sustain a species in all its stages of life then the hope is that it will be able to self-sustain and minimal human intervention will be needed to keep that population healthy.

As we have found during this project that P. verticillatum has quite a slow germination rate we have carried out a small mini trial with our translocated seeds. P. verticillatum berries have a juicy red flesh (not to be eaten as midly toxic!) but inside each berry is around 2/3 little and almost translucent seeds. We want to see whether the red flesh plays a part in germination rate, so at each site we sowed 4 bags of seeds with the flesh on and 4 with the flesh off. Taking the flesh off each berry involved putting the berries into a muslin bag, rubbing it with hot water to detach the flesh from the seed and then patiently picking out the little jewels out of the vibrant red mess with tweezers.

These autumn translocations have been a challenging but extremely rewarding process. Growing them in the nursery is one thing but being able to prepare them for their new homes and then actually plant them into Scottish soil is quite something. Seeing the van filled to brim with crates of native plants to then driving back to Edinburgh in a much lighter vehicle knowing that there are now hundreds of threatened natives back in their natural landscape is very fulfilling. I’m super excited (and slightly nervous) to find out how successful our translocations have been when the team goes out next year to monitor.

As always, we want to give a massive thank you to all our partners across the project who have been so great at helping us out these last few months. We appreciate it and I’m sure the Scottish native plants do too!

By Pablo Bell Molina

This project is supported by the Scottish Government’s Nature Restoration Fund, managed by NatureScot.

Instagram @rbgescottishplants

X @TheBotanics

X @nature_scot

X and Facebook @ScotGovNetZero

Facebook @NatureScot

#NatureRestorationFund