The following blog posts on moss evolution are written by Diego Sánchez-Ganfornina (early career researcher).

Migrations, extinctions, rainforests and climate change: the pressures and situations that led tree mosses to grow all around Australasia and subsequently, the world.

After exploring how mosses generally evolved and what evolutionary path a particular group (Hypnodendrales pleurocarps) followed in part I and part II of this saga on moss evolution, we now interpret how continents in the past few million years have changed immensely and what this means for small mosses!

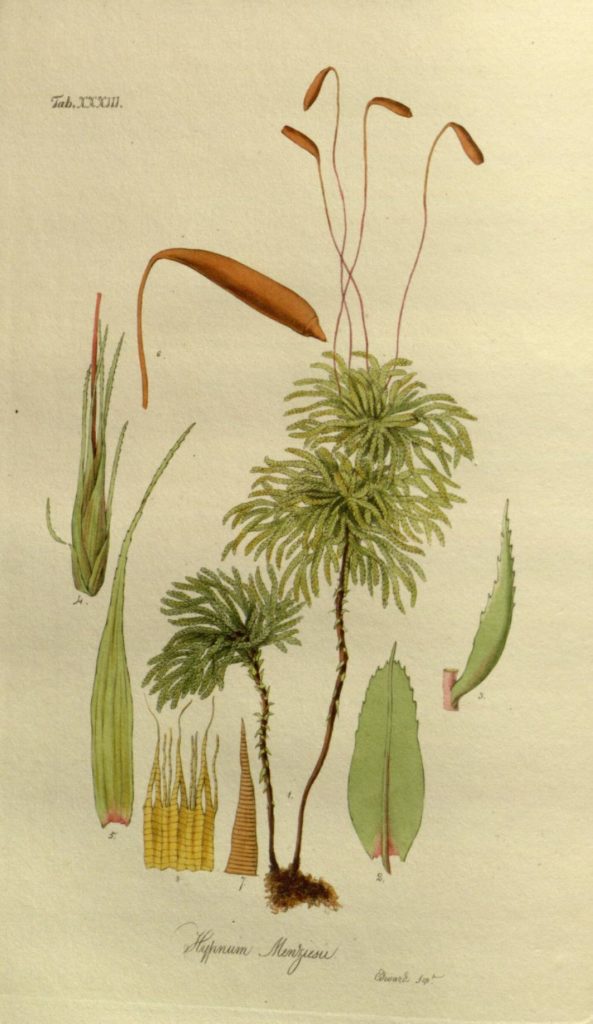

The earliest drawing of what is now known as Sciadocladus menziesii (back then considered Hypnum menziesii), one of the focus species we studied in depth in the Hypnodendron project. This moss grows in New Zealand and New Caledonia, and presents layered umbrella-like branches. It is in family Pterobryellaceae, order Hypnodendrales.

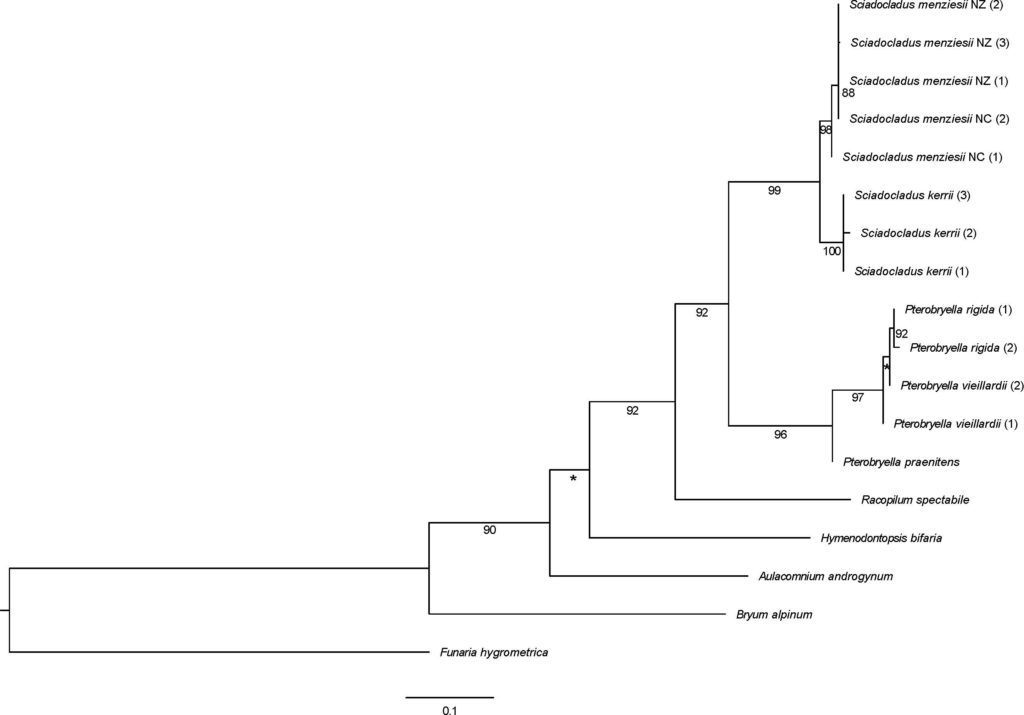

A specific example of a moss genus that has travelled through different continents in the past is Sciadocladus (pronounced “Skye-ah-doclayee-dus”). This tiny genus, comprised of two species, is now found in New Zealand and New Caledonia. When looking at these species in detail and using fossils to support a dated phylogeny, we find that the genus Sciadocladus diverged from its sister genus Pterobryella approximately 67.04 million years ago (see figure below).

This phylogeny focusses on the relationships between Sciadocladus species and the sister genus Pterobryella. However, this phylogeny doesn’t present dates for every node: to find these, one must go back and look at the large phylogeny in part II: in that phylogeny one sees that the genus Sciadocladus separated from Pterobryella 67 million years ago, but the current diversity in Sciadocladus only appeared 19.6 million years ago. The time in between these two events in conjunction with the geographical information regarding where we find Sciadocladus today gives us clues to understand where Sciadocladus originally came from.

Although the processes of formation of the extant New Zealand and New Caledonia island groups are complex and there has been controversy to try explain their geological past, it now seems likely that both were entirely submerged at various points in the Paleocene and Eocene. This means that these islands where Sciadocladus is now only found were underwater after this genus originated!

The most logical way to understand what has happened in Sciadocladus’s evolutionary past is to suggest that Sciadocladus could have originally occurred on the Australian landmass and dispersed to New Zealand and New Caledonia in the later Eocene, subsequently becoming extinct in Australia as aridification and other environmental factors drove rainforest biomes towards the extreme western and eastern coastal fringes. This hypothesis cannot be set in stone, as more in-depth sampling and analysis would be needed to confirm such a labyrinthine story.

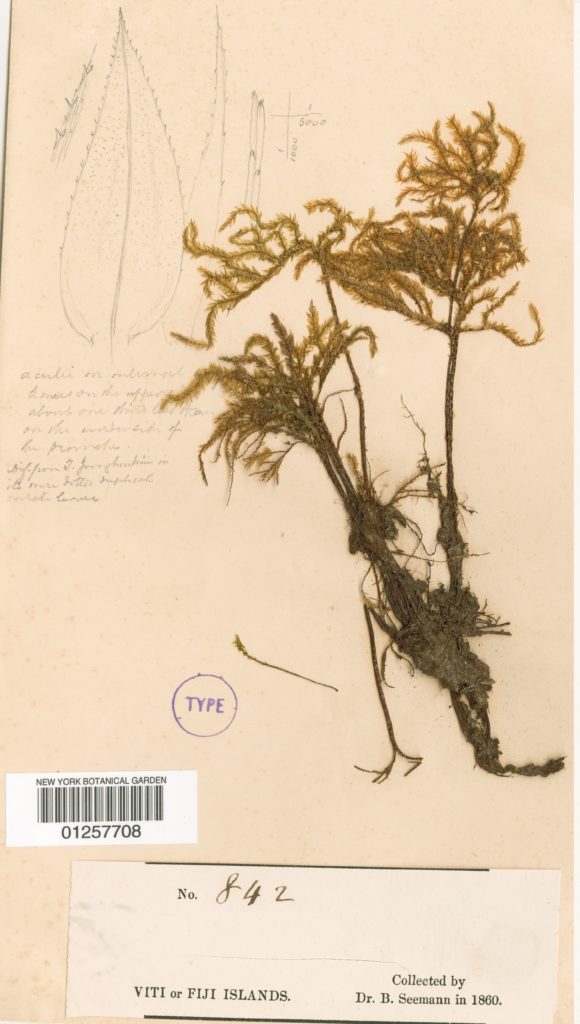

Digitised herbarium specimen of the type of Hypnodendron vitiense, another key species studied in detail in our project. It was collected in 1860 by Berthold Carl Seemann, a German botanist, in Fiji. The latinised version of Fiji is Viti, which explains its’ species name vitiense.

Another genus we explored, which gave name to our project, is genus Hypnodendron. This is a larger genus with many species, and we specifically focussed on two which looked like polar opposites: Hypnodendron vitiense is widespread, from southern Japanese islands to Tasmania, from Malaysia to Fiji (yet absent in New Zealand); Hypnodnedron marginatum is present solely on New Zealand and small islands nearby. We wanted to understand which evolutionary pressures and strategies had led to two species in this same genus to live in such distinct ways, occupying ranges so different in size.

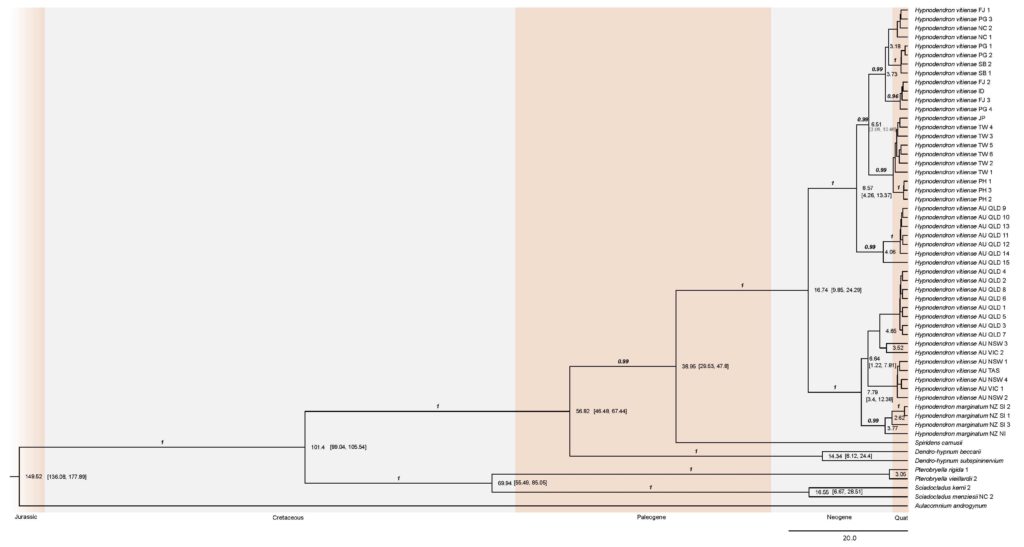

Hypnodendron vitiense focussed phylogeny, with dates on the nodes and blocks of brown and grey colour depicting the Jurassic, Cretaceous, Paleogene, Neogene and Quaternary geological periods. Credit: Diego Sánchez-Ganfornina and Neil Bell

As can be seen in the above phylogeny, Hypnodendron vitiense has arisen within the last 10 million years, and this can also be tracked back to the burst in tropical rainforests in the area. The way in which H. vitiense and H. marginatum relate to each other on our phylogeny is a puzzling discovery, with consequences for how we call these groups of plants.

Hypnodendron vitiense has a confusing taxonomic history, with two subspecies being described in the latest monograph on the family. These subspecies are easy to tell apart everywhere throughout their ranges except for those plants that grow in Queensland, Australia; where they are poorly developed and often don’t present the subspecies-distinguishing characters.

Hypnodendron marginatum presents all of its specimens in a group most closely related to what up until now is considered a subspecies of vitiense (H. vitiense subspecies australe). In taxonomy, we only consider species as groups that have a closer relationship to other specimens of their own group than to other species, yet the group of H. vitiense subspecies australe is more related to H. marginatum than to the other H. vitiense group.

To make things more complicated, the two H. vitiense groups overlap in one geographical area: Queensland, northern Australia, where the habitat conditions are generally dryer (and we hypothesise “tougher”), and this makes the plants growing there very hard, or impossible, to separate into each group just from morphology.

How shall we resolve these identification and taxonomic issues? This is our next step in research, as we consider the options on how to group these plants, and what consequences each option would have. We already have some ideas, but we want to collect feedback regarding our work and other useful bits of information from researchers reading our articles and local experts that are more often out and about in northern Australia to give us all their views before we make taxonomic decisions.

This project has constantly provided food for thought, challenged misconceptions about mosses being ancient unchanging plants, and thrown unexpected results at us: an enjoyable ride through research that we hope has also perked your interest, and will continue to provide further surprises: the investigation continues!

Research publications produced as a result of the Hypnodendron project:

- Sánchez-Ganfornina, D. & Bell, N.E. (2024). Phylogeny, chronology, and phylogeography in Australasian Hypnodendraceae. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society, boae020. https://doi.org/10.1093/botlinnean/boae020

- Sánchez-Ganfornina, D. & Bell, N.E. (2023). Species Delimitation in Sciadocladus (Pterobryellaceae, Bryophyta). Bryophyte Diversity and Evolution special issue, 46 (1), 119–124. https://doi.org/10.11646/bde.46.1.15

The Hypnodendron project would not have been possible without the support of the Sibbald Trust.