As 2015 draws to a close we end the third growing season for the Really Wild Veg project. The aim of the project is to explore how domestication has changed crop plants by comparing them with their wild ancestors in growing trials. As in previous years trials have been conducted here at the Botanics, by the Edible Gardening Project team, and at Redhall Walled Garden and Hermitage Vegetable Garden. A newcomer for 2015 has been Glasgow Botanic Gardens. Elizabeth Mittell, a PhD student with the University of Glasgow, is studying brassicas in order to explore the potential of this important group of crops in the context of increasing food demands and the stresses imposed by climate change.

Some of the growth trials at Glasgow Botanic Gardens have fed directly into the nutritional work being carried out by the Rowett Institute of Nutrition and Health as part of the Really Wild Veg project (see below). For more on Elizabeth’s work on brassicas check out her blog.

A particularly fun part of the project this year has been to explore taste preferences with members of the public in blind tastings. In general wild relatives of crops have stronger flavours. What we wanted to know was how people regard these flavours. Tastings at public events seemed an ideal opportunity to both engage a wider audience with the aims of the project and at the same time generate an indication of flavour preferences. To this end a series of blind tastings were conducted and the results are outlined below as the percentage vote for the best flavour:

Crop Circle discussion (panel of 47): Wild Cabbage 55% (26) vs. Cabbage 45% (21)

Crop Circle discussion (panel of 47): Wild Celery 70% (33) vs. Celery 30% (14)

SciMart market (panel of 71): Wild Cabbage 46% (33) vs. Cabbage 54% (38)

SciMart market (panel of 70): Wild Celery 51% (36) vs. Celery 49% (34)

Royal Highland Show (panel of 14): Wild Cabbage 79% (11) vs. Cabbage 7% (1) with 14% (2) undecided

So, in four out of five tests the wild plant gained a majority of votes, although in three of these cases the preference for wild over domesticated was not particularly marked. Despite not being scientifically robust data, these results do hint at a liking for more intense flavours.

Interestingly, a visiting group of students from Queen Margaret University studying for an MSc in Gastronomy also participated in a taste test with wild cabbage and cabbage. One might expect that such a group of highly-tuned palettes would be able to detect differences between the samples. The results below show a clear preference for the wild plant:

QMU student visit (panel of 15): Wild Cabbage 73% (11) vs. Cabbage 27% (4)

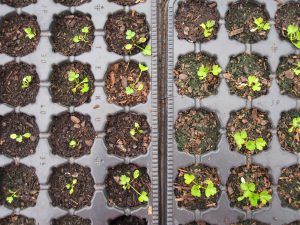

Celery trial plots at the Botanics showing wild celery (left), which is clearly less leafy and erect.

The format of the growing trials has remained the same in 2015. Three replicates of each species are grown side by side in blocks to try to ensure that environmental variation is kept to a minimum. The replicates represent different strains as follows: 1. wild type (where possible collected from the wild); 2. heritage variety; and 3. modern F1 hybrid cultivar. Samples of each strain in a trial were sent to the Rowett Institute of Nutrition and Health for analysis of phytochemical content with a focus on compounds linked to prevention of diabetes, cancer and heart disease. In addition, each strain was scored for productivity by weighing a specified portion of the crop. Plant health issues were recorded to see if certain strains display greater resilience and, as noted above, blind tastings were conducted to assess flavour preference.

During 2015 the focus on brassicas and celery has generated relatively few new results for productivity. Brassica trials have been conducted every year and additional data on productivity was not needed. For the celery trials the only data available at the time of writing is presented below. These data are from a sample of eight plants of each of the three strains grown at the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh by the Edible Gardening Project. In each case only the above ground parts were weighed:

Wild Celery – 368g, 162g, 178g, 152g, 133g, 130g, 159g, 51g with a total of 1,333g and a mean of 167g

Heritage Celery – 197g, 405g, 155g, 428g, 141g, 49g, 283g, 289g with a total of 1,947g and a mean of 243g

F1 Hybrid Celery – 175g, 197g, 240, 436g, 350g, 147g, 427g, 412g with a total of 2,384g and a mean of 298g

These results fit an expected pattern in which F1 hybrids are most productive and wild ancestors least productive. Domestication is to a large extent driven by a desire to increase productivity so we would expect wild plants to be relatively unproductive. In the case of F1 hybrids the crossing of two genetically distinct strains to create the F1 hybrid is the source of what is known as hybrid vigour. One manifestation of this is increased growth, and this explains why F1 hybrid strains are so commonly available to the home grower.

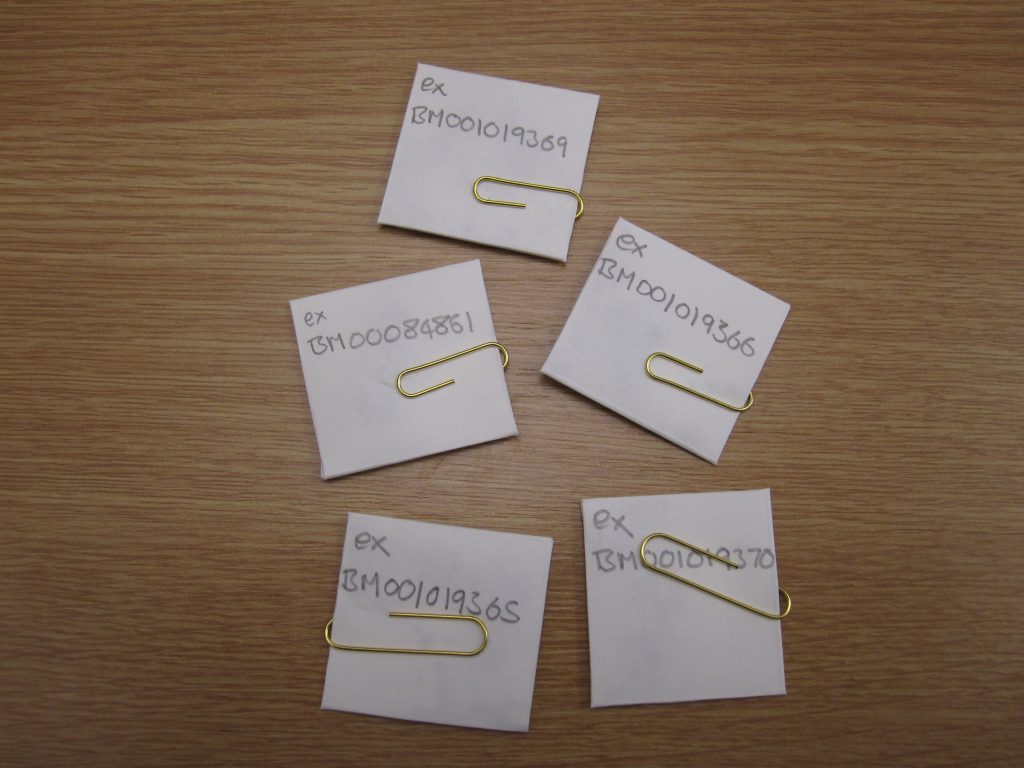

During 2016 the investigation of edible wild plants as novel crops will move away from Scottish native crop wild ancestors. We plan to grow trials of black nightshade (Solanum nigrum) collected in the UK and from a seedbank in Holland. This species is a weedy member of the potato family that is semi-domesticated in some areas (particularly Africa) and grown as a versatile crop that has edible leaves and fruits. In Scotland it is not native, but we are confident it will grow here as our herbarium has numerous examples of this species collected in Edinburgh and elsewhere in Scotland over the last 100 years or so. Most of these are garden weeds or accidental introductions with imported products. As a result many of the records are from Leith, a major trading port in the past. To start this exciting new project off with some UK origin seeds the Natural History Museum was contacted and has kindly supplied a selection of fruits removed from recently collected herbarium specimens (see below). It will be interesting to see if these seeds are still viable, but if not the Dutch seeds will enable a range of trial plots to be grown so keep your eye out next spring in the area adjacent to the Queen Mother’s Memorial Garden.

Steve Jones

Interesting trials, so what you lose in quantity you gain in taste. A pretty good compromise in my book.

Max Coleman

Yes flavour seems to be one of the potential benefits, although we should not forget potential pest and disease resistance traits that are potentially present in the wild ancestors too.

Silvia Bruznican

Hi Max, did you continue with any other studies on celery? Did you publish any of these data? I am busy with writing an review on celery breeding and would like to include some of your results.

Cheers,

Silvia

Max Coleman

Hi Silvia,

Good to hear from you and I’m pleased you have found our work interesting. The nutritional results are still to be published, but I will see if there is anything relating to celery specifically that we can share with you.

Best wishes,

Max