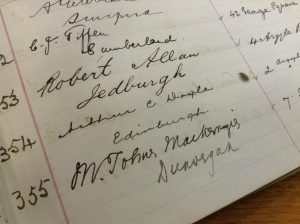

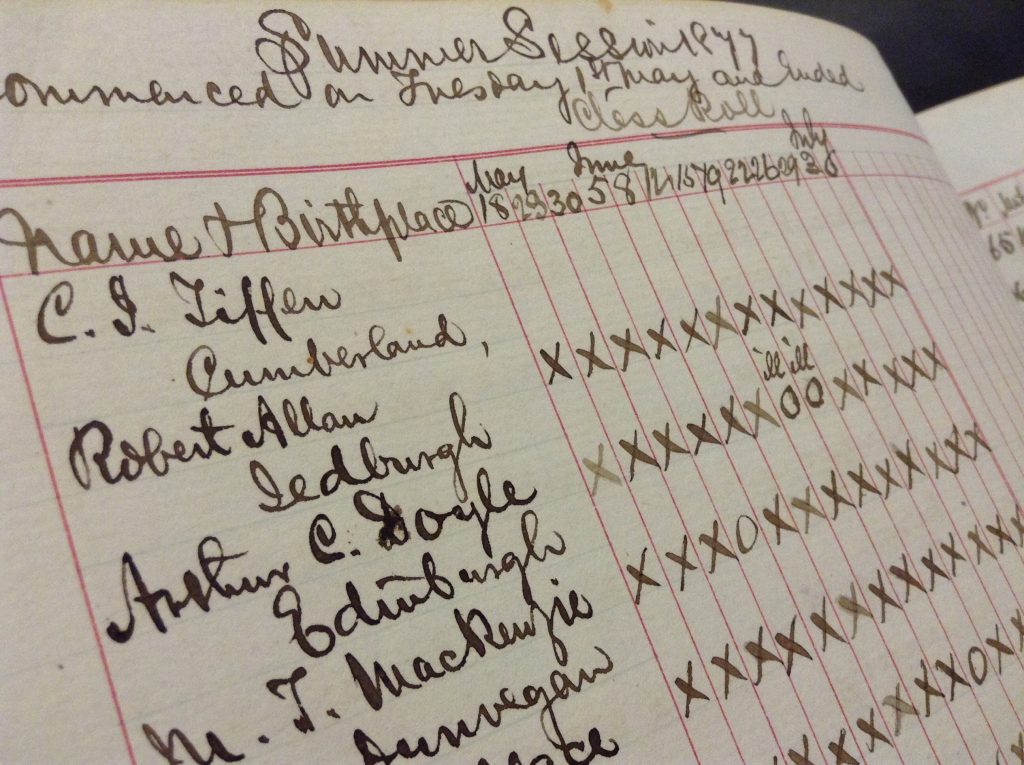

In amongst the institutional archives of the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh are items relating to the teaching of botany here, including lists of students going back to 1798. It occurred to me that it should be possible to find amongst these lists the name, and perhaps even a signature, of someone still in the public eye today, someone who had studied botany in the past, perhaps as part of a medical degree. These flights of fancy are usually fruitless, but this time it wasn’t long before I actually did spot a name still familiar to everyone, especially now that his stories about the detective Sherlock Holmes are enjoying a popular resurgence – that of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. His signature can be found in two of our Class Roll books, showing that he attended lectures here in medical botany and vegetable histology in 1877.

Library volunteer Diana Wilkinson has looked at Doyle’s early life and his time at Edinburgh University and has written the following post for Botanics Stories:

Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle was born in 1859 at 11 Picardy Place, Edinburgh (aerial photo, monuments) the eldest son and third of nine children of Charles Doyle, an artist and draughtsmen and his wife Mary. In 1867 the Doyle family moved to an overcrowded tenement flat at 3 Sciennes Place, Edinburgh, where Arthur headed a local street gang of boys. Funded by wealthy uncles he attended Hodder preparatory school from 1868 to 1870 and Stoneyhurst College from 1870 to 1875, then spending his final year of schooling in Feldkirch, Austria. In 1876 Conan Doyle entered Edinburgh University Medical School.

While at medical school Conan Doyle started writing and his first published story ‘The Mystery of Sarassa Valley’ appeared in Chamber’s Edinburgh Journal in September 1879. In the same month he published his first non-fictional article ‘Gelseminum as a poison’ in the British Medical Journal. His university studies were interrupted by work as a doctor’s assistant in Birmingham and service as a ship’s doctor on a Greenland whaler and he graduated MB CM in 1881 (alumni entry). He added his MD, also from Edinburgh, in 1885 (title page of thesis).

Conan Doyle built a successful medical practice in Portsmouth and in 1885 married Louisa Hawkins. His literary career progressed apace, developing the short story format from the examples of Guy de Maupassant and the Edinburgh medical journal articles. The first Sherlock Holmes and Dr.Watson story ‘A Study in Scarlet’ was published in 1887 in Beeton’s Christmas Annual.

In 1891 Conan Doyle moved with his family to London and in that year the Holmes and Watson stories began appearing regularly in the newly founded Strand magazine. Because Conan Doyle feared he would only be known for his detective stories he killed Holmes off in ‘The Final Problem’ in December 1893 and turned his attention to historical fiction (though Holmes was resurrected in 1903). He continued to have some involvement with the University of Edinburgh, establishing a scholarship for a student in the Faculty of Medicine in 1902. His wife Louise died in 1906 and the following year he married Jean Leckie with whom he had 3 children. He continued writing and in his later years developed a strong interest in spirituality. Conan Doyle died at his home in Sussex in 1930 (letter written from his home in Sussex).

Connection with the Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh

In order to graduate with a degree in medicine from the University of Edinburgh at that time, students were required to have undertaken 4 years of education and, in each year, to have attended two six month courses of lectures or one of six and two three month ones. In practice (according to his memoirs) Conan Doyle compressed his classes into half a year in order that he could earn money to support his studies and his family working variously as an outpatient clerk to the influential Dr. Joseph Bell (portrait), as a medical assistant in Birmingham and on board the Greenland whaler SS Hope from February to August 1880.

Botany was a compulsory subject and medical students attended a three month course of lectures at the Royal Botanic Garden (RBGE) for every year of their studies, totalling no less than 50 lectures. Botany was then examined as part of their Professional examinations along with subjects such as anatomy, chemistry, Institutes of Medicine, Surgery, etc. Botany exams, as far as possible, were conducted by demonstrations of objects placed before the candidates and through written and oral examinations.

As part of his degree Conan Doyle completed a summer course on Vegetable Histology and Practical Biology at the Royal Botanic Gardens Edinburgh, attending lectures on 4 days a week from May to July 1877. At that time he was living at 2 Argyle Park Terrace, listed in the Post Office Directory as possibly a lodging house run by a Mrs. Burnside with one female and four male residents including Conan Doyle.

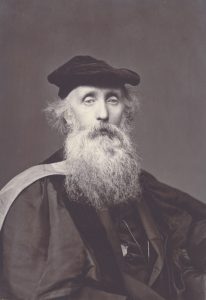

According to his own ‘Memories and Adventures’ published in 1924, Conan Doyle did not enjoy his medical training describing it as ‘one long weary grind at botany, chemistry, anatomy, physiology and a whole list of compulsory subjects many of which have a very indirect bearing on the art of curing’. In these recollections he describes his various professors including Professor J. Hutton Balfour who was Regius Keeper of the Botanic Garden between 1845 and 1879, as well as Professor of Botany at the University. “Balfour, with the face and manner of John Knox, a hard, rugged old man who harried his students in their exams, and was, in consequence, harried by them for the rest of the year”.

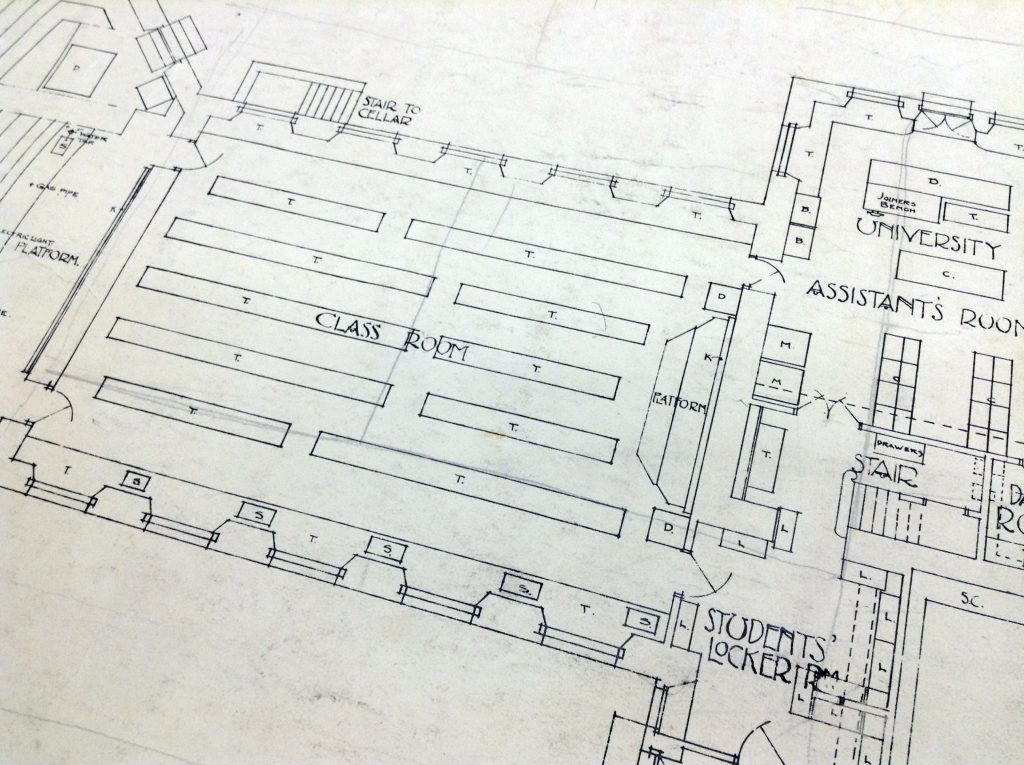

Plan in the RBGE Archives showing the classroom layout in the 1880-90s. This is now our conference room.

At that time those studying botany at the Botanic Gardens did so in some discomfort. The Regius Keeper’s Report for 1877 notes the lack of funding to run the gardens and particularly the poor state of accommodation for students. He comments that the class room could accommodate a maximum of 230 students yet numbers attending were 389 (students of medicine, science and pharmacy as well as general students) and that he was compelled to lecture in “an over-crowded room, the vitiated air of which is injurious to the health of the lecturer and his pupils”. Students regularly petitioned the Office of Works and the Regius Keeper as well as the University and in 1878 provided details of the severity of the overcrowding; “Every possible means have been taken for getting accommodation by filling the passage with stools and forms, occupying the platform where the Professor lectures, removing an important table for holding the plants for demonstration, and by filling the outer lobby with seats”. There is no record of Conan Doyle attending lectures at the Botanic Gardens after 1877 as far as we know, but despite the conditions, botany was the only subject within his degree course which Conan Doyle was known to have excelled.

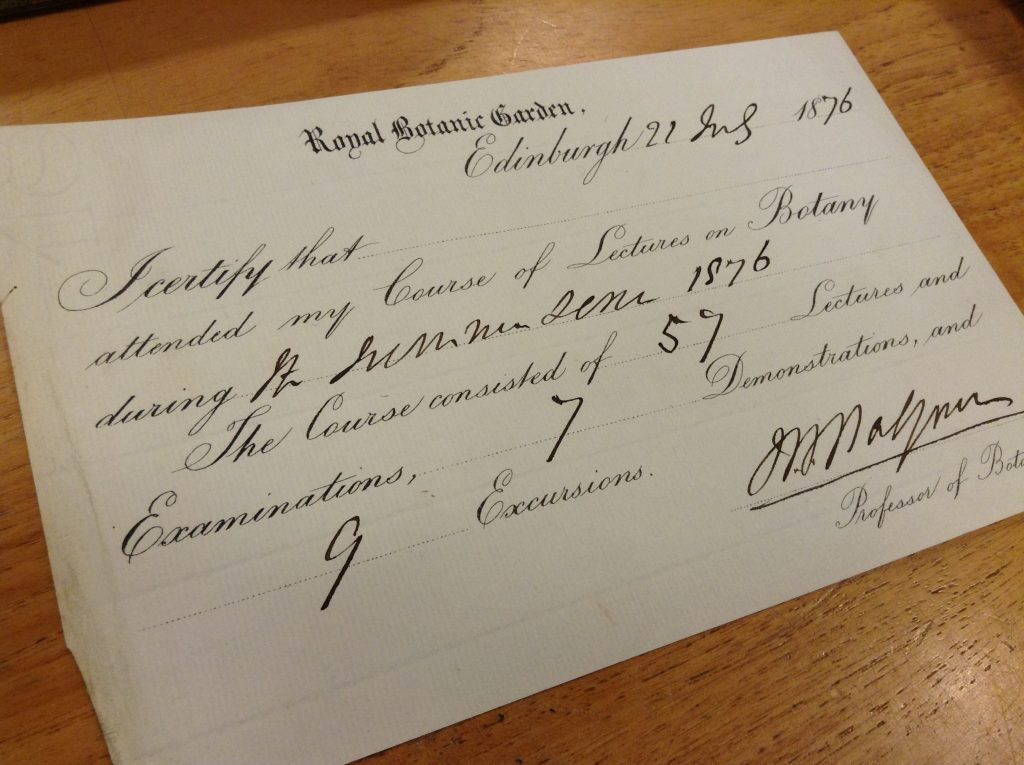

Certificate issued by John Hutton Balfour in 1876 at the end of the Botany course – presumably Conan Doyle would have received a similar one the year after.

Conan Doyle draws on his experiences in his partly autobiographical thriller ‘The Firm of Girdlestone’ published in 1890. One of the minor characters, Tom Dimsdale, is a medical student at Edinburgh University. In Chapter 9, entitled ‘A Nasty Cropper’ there is a detailed description of Tom’s botany exams and his examiner. “This venerable teacher of botany, though naturally a kind-hearted man, was well known as one of the most malignant species of examiners, one of the school which considers such an ordeal in the light of a trial of strength between their pupils and themselves”, which sounds rather like his description of Balfour in his memoirs.

Conan Doyle clearly draws on his medical knowledge including botany and the use of plants as poisons in his Sherlock Holmes stories. Dr. Watson ‘Knowledge of Botany: Variable. Well up in belladonna, opium, and poisons generally. Knows nothing of practical gardening’ as one of Holmes’ 12 strengths and weaknesses and refers to his knowledge of botany in other contexts e.g. in ‘The Study in Scarlet’.

Credit goes to Diana Wilkinson for writing this Botanics Story, which although about Conan Doyle has actually shed some light on Hutton Balfour as a teacher which I found particularly interesting. Diana received a little help from Lorna Stoddart who is working on a PhD on Balfour, and myself, and I’m grateful to Elspeth Haston and staff at the National Galleries of Scotland, Historic Environment Scotland and the Edinburgh University Library for working on linking this Story with other collections across Edinburgh. The collection of student class roll books is currently being listed by library volunteer Anne Taylor.

Leonie Paterson, Archivist at RBGE

Howard L Minnick

Could there be any possibility of records pertaining to Patrick Matthew known Forester and Orchardist having attended similar lectures, classes and events during his brief studies at Edinburgh also leaving a written record of his attendance? Patrick Matthew and his son John D. Matthew are credited with introducing the first California Redwoods to Europe in August of 1853 4 months prior to John Lobb getting a packet of seeds from the same Calaveras grove that John D. Matthew gathered his seedlings and smaller seed packet from. John Matthew beat Lobb because his father told him to send his packet by steam ship mail rather than by standard sail packet mail. It has also recently been discovered that the new editorial staff of the Gardeners Chronicle in 1866 a year after his death corrected the myth that John Lindley their own editor was the first to suggest that the Redwoods were first introduced by Lobb and that he himself (Lindley) was the one to suggest naming the trees Wellingtonia gigantea. In their own publication the Gardners Chronicle reversed both priorities and attributed both to John D. Matthew and the first plantings by Patrick Matthew at Inchtures as the first ever out of their native indigenous California habitat.

Deron Hicks

What address is listed for Doyle on the 1877 class roll?