The 21st March 2018 marks the centenary of the death of Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh (RBGE) Helper James Christopher Adam. He was the older brother of RBGE’s photographer Robert Moyes Adam.

James was born on Christmas Day 1882 in Carluke, Lanarkshire, the son of Reverend John Adam, Evangelical Union Independent Minister of Kirk Memorial Independent Chapel, and Isabella Moyes Adam. They and James’s two younger brothers Robert and John Fraser and two sisters, Lizzie and Margaret eventually came to live at 15 Brunswick Street, Edinburgh. At the age of 18 James was a Bookseller’s apprentice, but his obituary in the Scottish Naturalist written by his friend S.E. Brock in 1918 (no.73-84, p.238) doesn’t mention this, concentrating instead on James’s love of nature, and birds in particular:

“slow to make friends, he was known intimately by few… In nature, birds were his first, and greatest, love, and almost every minute of his spare time, from early boyhood onwards, was spent, usually in the company of his younger brother, R.M. Adam – in exploring the neighbourhood of [Edinburgh] and the greater part of the Lothians; while once or twice a year, longer excursions would be made to the Highlands or Hebrides. A few years before the war he received an appointment at the Royal Botanic Garden [12th April 1912], and although going there almost entirely ignorant of botany, he took it up with his usual whole-hearted enthusiasm, and in a wonderfully short period became an excellent field botanist. Latterly he took up mosses, and his rapid progress in that difficult group promised that he would soon have achieved a high position amongst Scottish Bryologists.”

R.M. Adam’s photo of his brother J.C. Adam holding camera equipment and being attacked by a black headed gull on what is now known as the Flanders Moss National Nature Reserve in Stirlingshire, 1909. Ref RMA-S-717 -X, courtesy of the University of St Andrews Library who hold a large collection of R.M. Adam’s photographs in their Special Collections.

We also know that James and Robert shared a love of the great outdoors and Scotland’s natural history because in 1905 James accompanied Robert on a trip to Mingulay to record the wildlife and scenery there. By this time Robert had gained employment at RBGE as a photographer, and as we’ve seen, on the 12th April 1912 James joins him as a Helper. It’s clear from the obituary above that James was involved in plant identification and taxonomic work, presumably in the Garden’s herbarium and it seems that describing his position as ‘Helper’ underplays its significance; ‘Assistant’ might be the term used today. The post involved writing publications that he could add to papers he’d already written on ornithology, and clearly James had a bright future ahead of him. But war intervened.

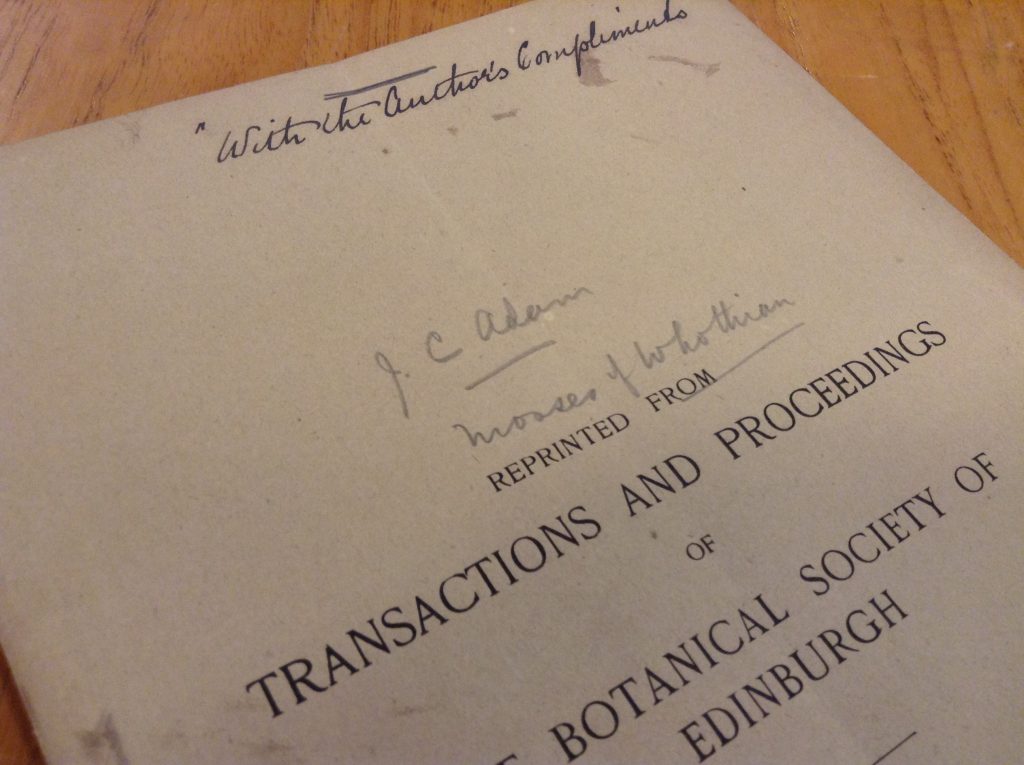

Signed copy of James C. Adam’s ‘Mosses of West Lothian’, read at the Botanical Society of Edinburgh meeting on the 8th February 1917. RBGE Archives.

James and Robert enlisted on the same day, the 17th January 1917; curiously just under a year after the Military Service Act came into force. This Act meant that the brothers would have had little choice but to enlist at the beginning of 1916, unless they were in a reserved occupation or had another good reason. Their younger brother Fraser was already in the army, he enlisted in March 1915. It seems likely that James and Robert would have attested in late 1915 or early 1916 – this would have intimated their intention to serve but if they were in a reserved profession, or had good reason, they could apply for an exemption or a period of delay.

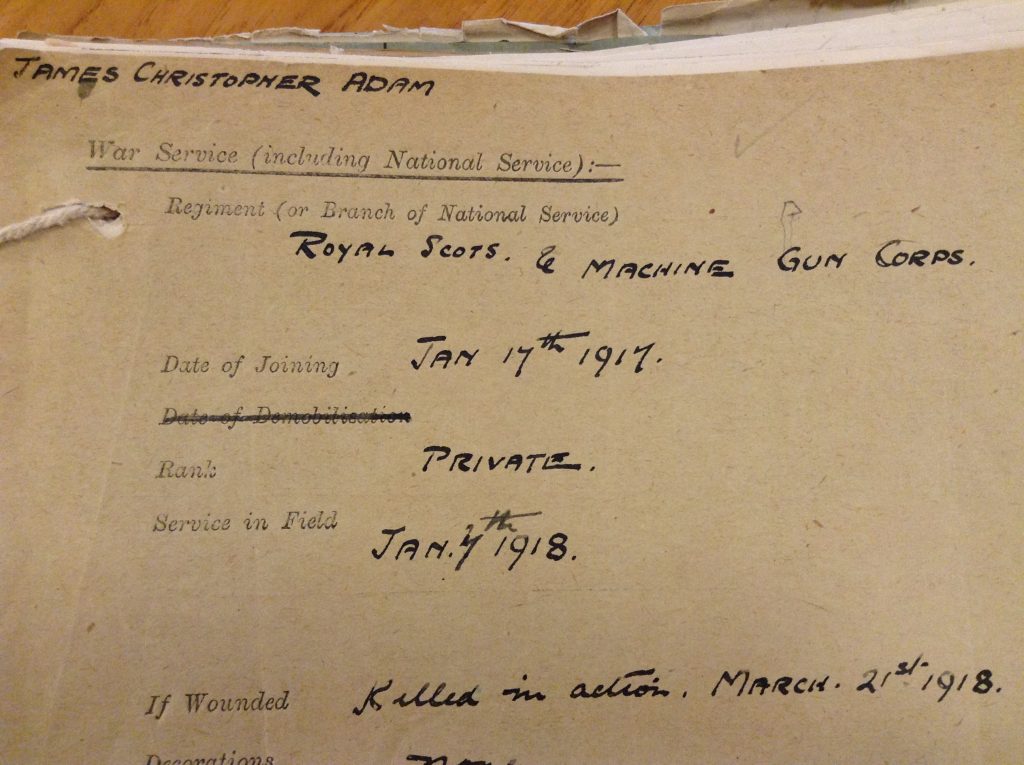

Private J.C. Adam’s War Service card in the RBGE Office of Works War Memorial file, poignantly written in R.M. Adam’s handwriting.

It may have been that Robert and James were engaged for a time in work vital to agricultural or medical research; the Garden was involved in work for the Timber Supply Department and in the identification and properties of sphagnum moss, used to make hospital dressings. Though it may be that their involvement in scientific botanical research was a valid enough reason. We know Robert was assisting the Garden’s Regius Keeper, Isaac Bayley Balfour with his taxonomic research as he was taking magnified photographs of primulas and rhododendrons using a microscope and Balfour wrote in February 1917 in the Transactions of the Botanical Society of Edinburgh (v.27 p.163) that:

I had hoped, having the advantage of the co-operation of Mr R.M. Adam, Assistant in the Studio here, whose skill as a photographer is unrivalled, to have been able to provide a series of illustrations from microspecimens of typical forms of indumentum [of rhododendron] and many of them have been prepared, but he is now doing more valuable work in serving the guns, and who shall say that our intention will reach fruition.

It may be that the reason for their delay lay with their family – their father was suffering from stomach cancer and died at the end of June 1916. Without the military service records of Robert and James it is impossible to say, but whatever the reason, it ceased to exist in January 1917, either because the work they were engaged in came to an end, their exemption period came to an end, or, more likely, this is the time that the army, desperate now for more men, began to review previous exemptions with a stricter eye and call up men whose reasons no longer passed muster. Isaac Bayley Balfour, stated at this time (in a letter to Reginald Farrer, 9th Feb 1917) that he felt that every man fit to serve should serve, but

no-one in my Garden including myself was indispensable. I have been taken at my word and excepting Mr. Harrow and a youngster who was discharged from the Army after some months’ service I have not a man looking after my plants who would have been allowed to come near them in the old days…

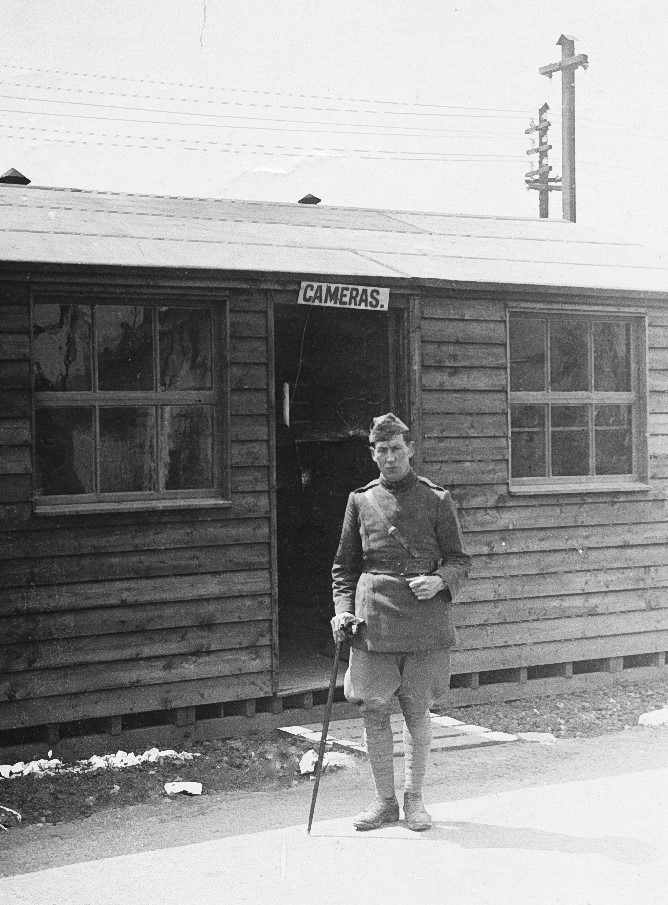

R.M. Adam at the Farnborough Photography Training School in 1917. Photo courtesy of the Adam family.

James and Robert left the Garden together to join the army, but were allocated different regiments; Robert became a Bombardier in the Royal Garrison Artillery, later transferring to the Royal Flying Corps where he attained the rank of Lieutenant, and James became a Private in the Royal Scots, later being transferred to the 59th Company, Machine Gun Corps (Infantry).

Robert Moyes Adam served for a time on the Western Front. His grandson once asked him what he remembered about it and he replied that it was the terrible stench of death, awful and unforgettable. Perhaps this was why he grabbed the opportunity to leave the Royal Garrison Artillery when given the chance to join the Royal Flying Corps, though the risk to life would still have been significant, perhaps even more so. My guess would be that joining the Royal Flying Corps would have given Robert the chance to be a photographer again, and likely the need for experienced photographers to perform vital aerial reconnaissance work would have been the reason for his move there. We know from another of Isaac Bayley Balfour’s letters, this time to the plant collector George Forrest, who was collecting in China, that R.M. Adam was engaged in aerial photography work and he was training others how to do it. At the end of the war he was asked to remain with the Royal Air Force, newly formed from the Royal Flying Corps, but, keen to return to the Botanics, he refused and was demobilised on the 3rd February 1919.

Lt. R.M. Adam (centre) with his RAF unit labelled 65th Wing, Dunkirk. Photo courtesy of the Adam family.

James’s war did not go the same way. He was transferred to the 59th Company Machine Gun Corps, entered France as a theatre of war around December 1917 and found himself on the Western Front going with his battalion wherever machine gun support was required. This meant he was right on the front line when the Germans launched what became known as the Spring Offensive of 1918. Bolstered by troops newly arrived from the Eastern front after revolution pulled the Russians out of the war, this was Germany’s last chance push into Allied Territory before the imminent arrival of American troops on their way to bolster the Allied efforts. The British were expecting an imminent attack as aerial observers (one wonders if Robert was one of them) had spotted the build-up of German forces from above. Despite this, it started very successfully for the Germans – at around 5am on the 21st March 1918 a massive bombardment commenced along a 54 mile section of the front using gas and high explosives. During the first five hours of the attack one million shells were fired at the British. The machine gun posts would have been prime targets, presuming the enemy could see them, a thick fog that morning rendering them practically useless (Sir Douglas Haig’s Despatch). The War Diary for the 59th Machine Gun Corps lists, as is usual for war diaries, the dead, wounded and missing at the end of each month: on the 31st March 1918, from O.R. (Other Ranks), there was 1 killed, 15 wounded and 316 missing – this paints a very vivid picture of the chaos and confusion that must have reigned after the onslaught, as the number killed and wounded was undoubtedly vastly higher. James was one of the missing, later declared dead. He was 36 years old. His body was never found; his name instead listed on the Arras memorial, Pas-de-Calais, France.

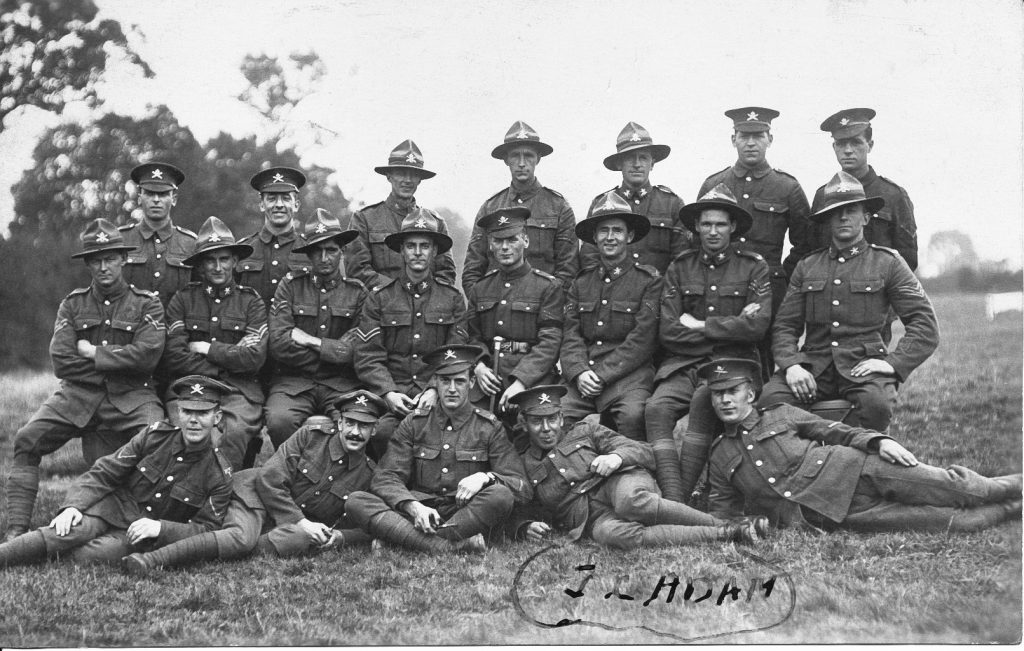

J.C. Adam (indicated by his name in his brother’s handwriting) with his battalion and New Zealand soldiers in February 1918. Photo courtesy of the Adam family.

It’s worth mentioning, to complete the picture, that James and Robert’s younger brother, John Fraser Adam, who had been born in Carlisle on the 8th July 1887, and attended the Royal High School, Edinburgh and University of Edinburgh, obtaining an M.A. in 1909, enlisted on the 29th March 1915 into the 9th Battalion (Highlanders) Royal Scots as a Private. In October 1915 he was commissioned into Princess Louise’s Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders (Territorial Force) as a 2nd Lieutenant. He was promoted again, this time to Lieutenant on the 1st July 1917, and later, again I believe to Captain. According to the University of Edinburgh Roll of Honour he was in France in October 1916, Italy in December 1917, before returning to France between April 1918 and March 1919 when he was presumably demobilised, returning home to pursue a career in teaching. He died in March 1937 at the age of 50.

Lt. J. Fraser Adam of the Argyle and Sutherland Highlanders, February 1916. Photo courtesy of the Adam family.

With thanks to Garry Ketchen for his genealogical research and permission to use it, and to Jane Campbell at the University of St Andrews for permission to use one of the images from the R.M. Adam photographic collection held there.

Thanks also to members of the Great War Forum who have been extraordinarily helpful by guiding me with their expertise and opinions as I’ve waded through the ins and outs of the Military Service Act. Any mistakes made in regard to this are my own.

Special thanks go to R.M. Adam’s grandsons David Adam and Alasdair Morrison who have generously provided me with reminiscences, photographs and support whilst I have been piecing this Story together. I could not have done it without them and the privilege of being able to see and use Adam’s photos of his brothers, as well as ones of himself in uniform is overwhelming. Thank you! I wish things had turned out differently for James, and the other men on our memorial, but hope that I have done him proud. We will remember him.

Jane Corrie

This is brilliant, detailed and very collaborative work you are reporting Leonie. Thank you so much. Jane C