The Himalayan region is recognised as one of the ‘hottest’ global Biodiversity hotspots, with a third of all plant species within its range occurring in Nepal. This makes documenting the Flora of Nepal very important.

A Flora documents all plant species within a specific geographical region. Each plant account in a Flora include the species’ scientific name, common names used in the geographical region, a description of its physical characteristics complemented by detailed illustrations, the habitat it is typically found in, its geographical distribution, and flowering and fruiting times. As you can imagine writing a Flora is a long process and involves gathering information about species in various different ways including previously published literature and going out on expeditions to collect plant specimens at different times of the year.

Floras of large scope are a collaboration involving many authors and contributors. The Flora of Nepal is no different, with the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh (RBGE) leading the project in collaboration with the Department of Plant Resources (DPR, part of the Ministry of Forests and Environment), Nepal Academy of Science and Technology (NAST), Central Department of Botany, Tribhuvan University (CDB-TU) and the Society of Himalayan Botany, Tokyo (SHB).

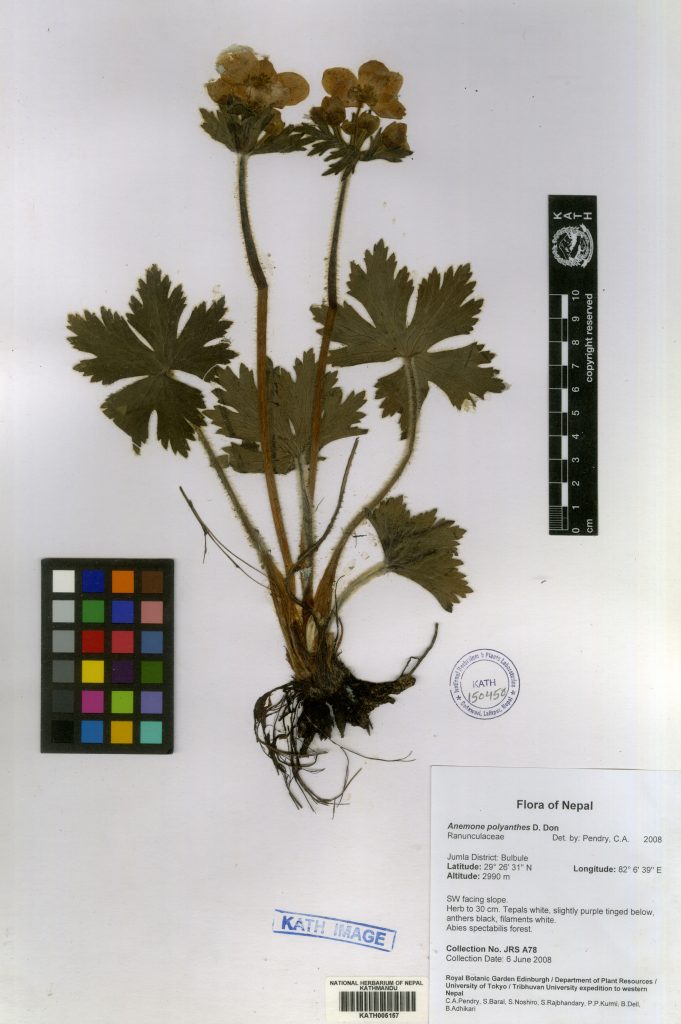

Specimens are a key resource, as they allow for identification of a species to be confirmed and provide other information about the species. When making a specimen, alongside the physical plant specimen specimen a botanist will write a detailed record containing information about the physical characteristics of the plant, the date it was collected and where it was collected. This collection information is printed onto a collection label which, together with the pressed plant specimen is mounted on archival card.

Ideally multiple specimens would be collected of each species at different times of year and from different areas of a geographical region to be able to build up the big picture of what species occur, where they occur and when they flower and fruit. These specimens are stored collectively in a single building called a Herbarium, allowing the puzzle to be pieced together.

In order to make these specimens and the data they contain internationally accessible for Flora writing, specimens must be digitised. Digitisation involves taking images of the physical specimens and typing up their collection label information into database records and making these available online. The National Herbarium and Plant Laboratories (KATH), Kathmandu, Nepal – part of DPR – is a small herbarium that contains approximately 165,000 herbarium specimens, but these represent 50% of vascular plant species and 25% of lower plant species known to exist in Nepal.

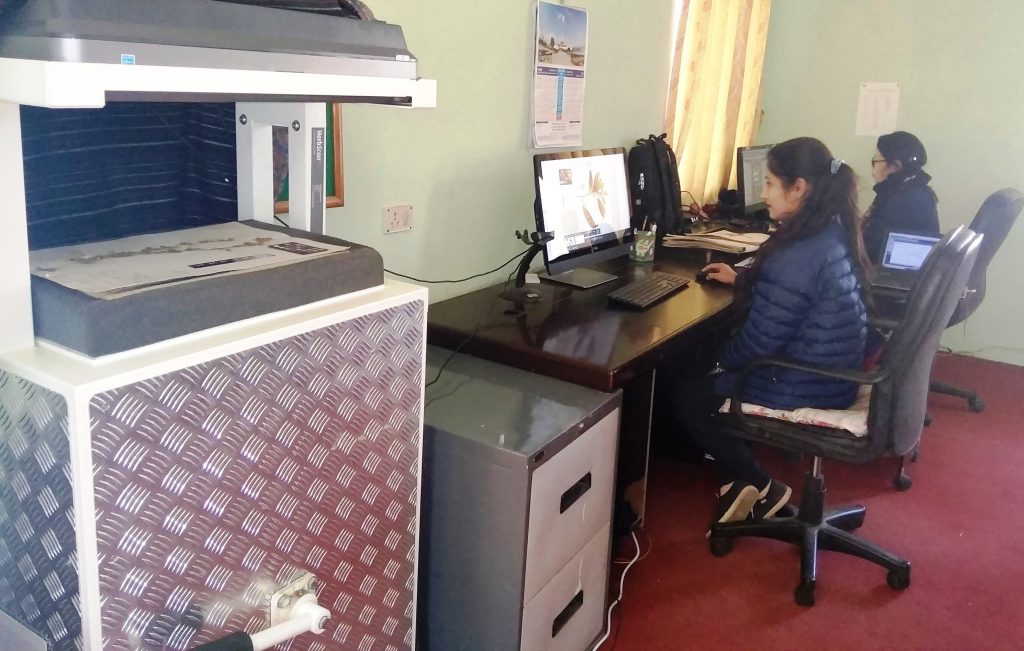

Its pre-existing digitisation programme enabled the digitisation of 70-75 specimens a day by three digitisers. Specimens were imaged at 600 pixels per inch using a single Herbscan. This enables botanists to zoom into images, like using a 10x magnification hand lens, to see hairs, and detailed flower structure.

The scanner is slow, with each image taking 6 minutes to scan; at this rate it would take 7 – 8 years to completely digitise the KATH herbarium. They were keen to switch to a camera imaging set-up, as many herbaria, RBGE included, have been able to increase their imaging rate by up to 500 specimens per camera per day.

An important part of RBGE’s work on the Flora of Nepal involves capacity building within the Nepalese partner organisations. As part of this I devised an affordable imaging set-up for KATH that creates high resolution images, collaborating with staff in digitisation departments at New York Botanical Garden, WTU Herbarium, Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture, and Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

In January 2019 I travelled with colleagues to Nepal and worked with staff at KATH to install the set-up and provided training on the imaging workflow required. With a week for installation there were challenges along the way including not all the equipment arriving on time from India and finding solutions to ensure the stability of both hardware and software with the frequent power cuts that occur in Nepal without ICT specialists.

In the end the installation has been a success and at the time of writing the digitisers have almost tripled the rate of digitisation to 180-200 specimens per day. This translates into approximately 3 years to digitise all specimens held at KATH herbarium. Not only will international access to the specimens expedite the flora writing process, but also make it possible to update species distributions which will tell help figure out which species are most threatened and need to be prioritised for conservation action.

For more information on the Flora of Nepal Project please have a look at the following resources:

https://kath.gov.np/Flora_of_Nepal

https://rbg-web2.rbge.org.uk/nepal/darwin/frames.html?collections.html

Pema G Bhutia

I wish, something like this could also happen to flora of Sikkim

Ganesh Joshi

Great.