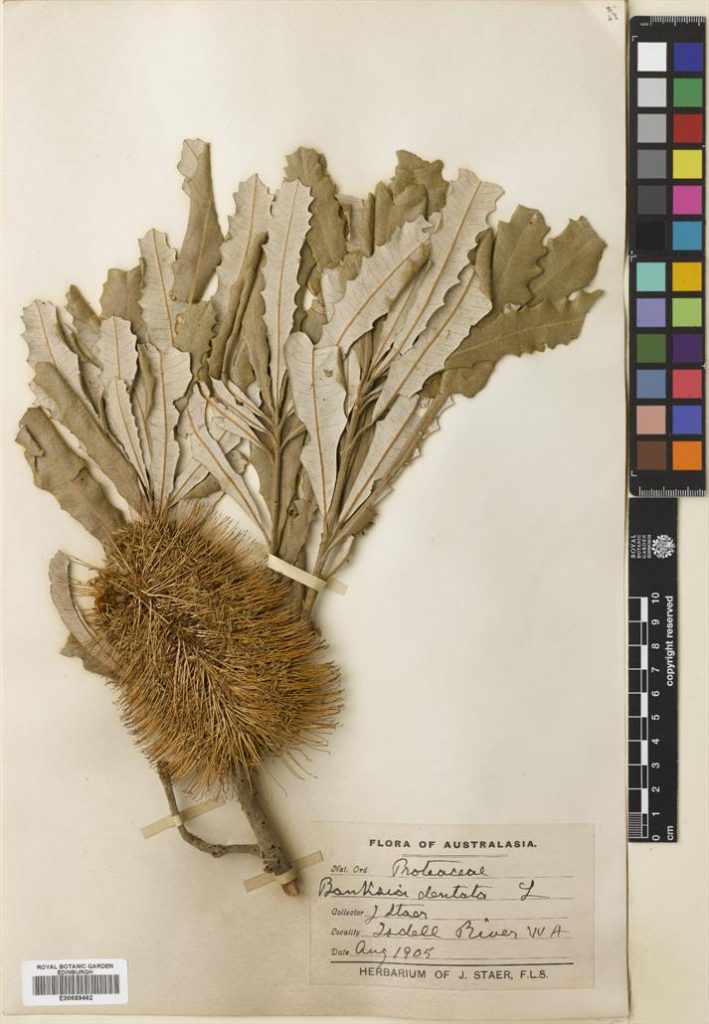

The herbarium at RBGE holds around 3 million herbarium specimens. Each specimen consists of pressed plant material and a collection label mounted on archival card. They are used to identify new species, establish their global distributions and explore evolutionary relationships. This research helps to provide an essential baseline for the development of conservation strategies and other disciplines, e.g. pharmaceutical research.

No one herbarium in the world has all experts in-house for every single one of the of the 457 plant families – and that’s just the number of flowering plant families! This means is really important to make our specimens digitally available online, for researchers across the globe to identify species and map their geographical distributions.

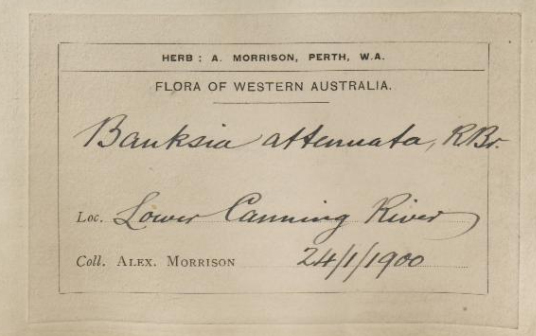

What’s in a collection label?

Collection label transcription is vital for botanists to carry out this research as the labels contain information about: the physical characteristics of the plant which may not be preserved after it has been pressed and dried, such as flower colour, the date it was collected, where it was collected – including details of the habitat it was found in – and who collected it. Capturing specimen information digitally allows researchers to build a picture of a species’ historical distribution; these can be compared to current distributions to see if any changes have occurred such as a decline in numbers. Specimen labels may also provide clues to help explain these changes, for example, habitat information recorded at the time of collection can be compared with current land use in the same locality. The specimens alongside the collection label can also be used to monitor phenology, such as flowering time. Changes in flowering time can be monitored and correlated with climate, meaning specimen data can provide us with information on the impact of climate change on plants and indirectly on pollinators too. Thus digitisation helps inform and target conservation efforts protecting plant species for future generations.

Full label transcription would take around 40 years for our three digitisers and that’s before you take into account the time it takes to image the specimens. With the rate of species loss being estimated to be at 1000 -10,000 above the naturally expected rate we cannot afford to take decades, we had to look for another way to speed up the process.

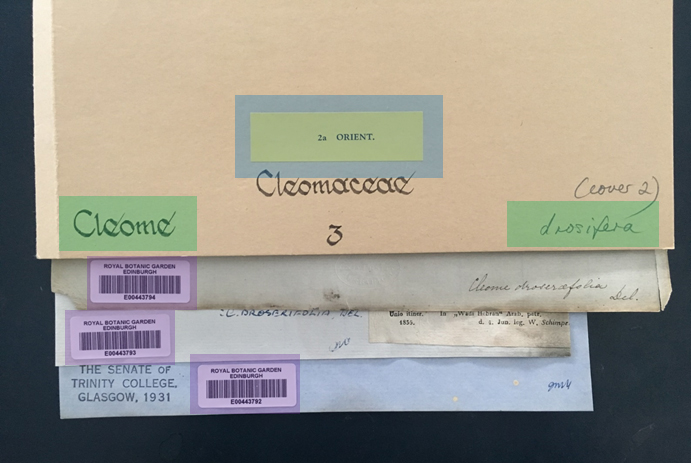

We switched to minimally databasing our specimens, a process which only records where the specimen is filed in the herbarium, but is up to 14 times faster than complete data entry. This meant specimens could be imaged and placed on our online catalogue much faster than before.

Whilst this makes our collections more visible it means individual specimens are hard to find and their full research potential is not easily accessible. This left us with another dilemma, how do we get the collection label data transcribed quickly?

The answer was to enlist the crowd…

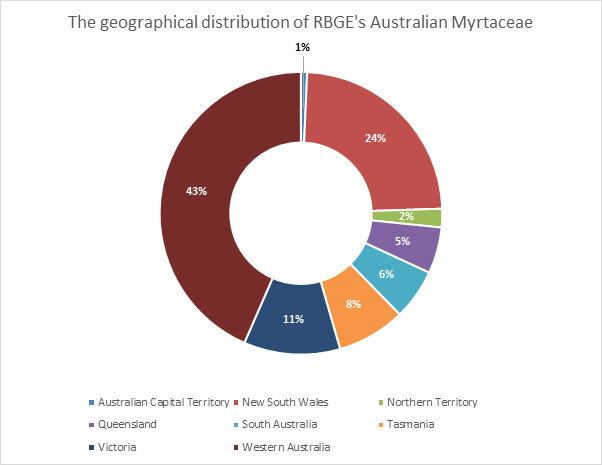

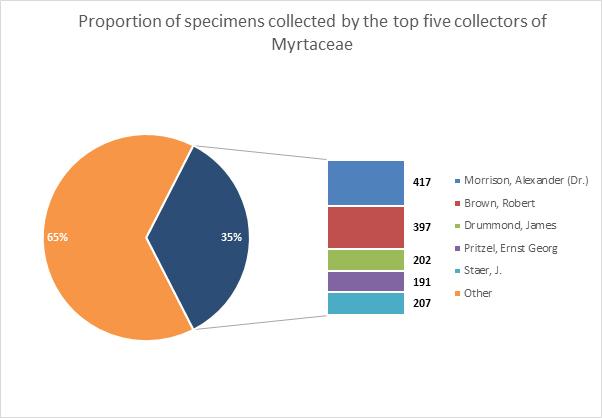

We had all our Australian specimens minimally databased and imaged thanks to the hard work of digitisers and funding provided by the Mellon Foundation and Friends of the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. To help us capture the label data digitally we decided to launch a project on DigiVol (https://volunteer.ala.org.au/), a Citizen Science platform on the Atlas of Living Australia (https://www.ala.org.au/). Citizen science platforms are websites where members of the public transcribe or categorise large sets of data allowing scientists to accomplish tasks that would be too expensive or time consuming to accomplish through other means.

Our first virtual expedition, ‘Proteaceae of Australia’, was launched as part of WeDigBio event, 19-22 October 2017 (https://wedigbio.org/). The Proteaceae is an iconic family distributed throughout the Southern Hemisphere with several well know genera such as Banksia and Grevillea coming from Australia. This project consisted of 3282 specimens and it took just 3 weeks for the volunteers on Digivol to transcribe them all. Following this first success, we regularly launched expeditions, with all 41,146 Australian flowering plant specimens in a total of 29 expeditions being completed in 15 months by 156 volunteers.

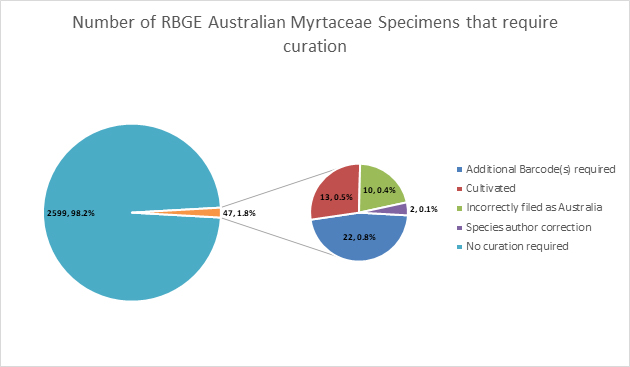

Crowdsourced curation

As well as providing the transcribed data from the specimens, the volunteers also highlighted curation issues. An unexpected but very helpful outcome of crowdsourced label transcription!

We passed this information back to the volunteers in ‘Thank you’ emails as well as summaries of what the expedition had revealed for each plant family explored:

The infographic below lets you interact with Dillenaceae Transcription data…

It was also an opportunity to provide answers to questions volunteers had and general feedback on any mistakes that were made.

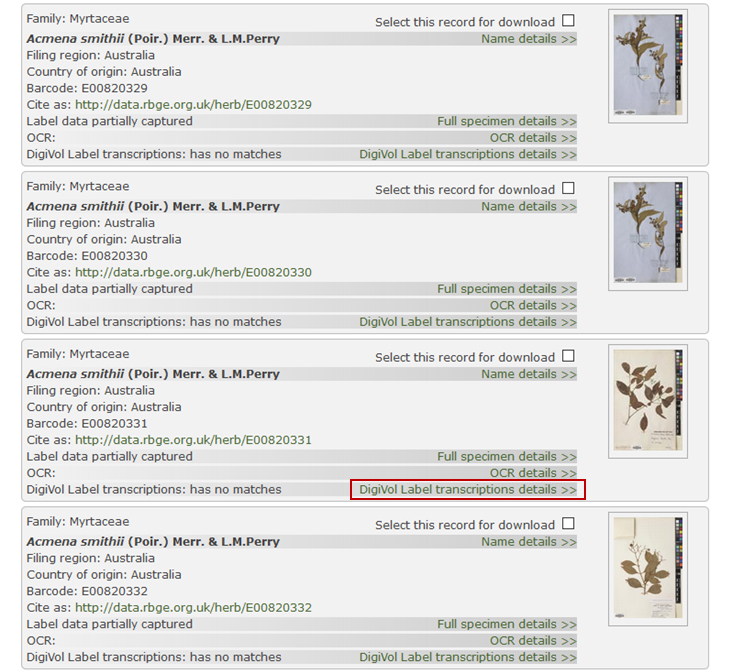

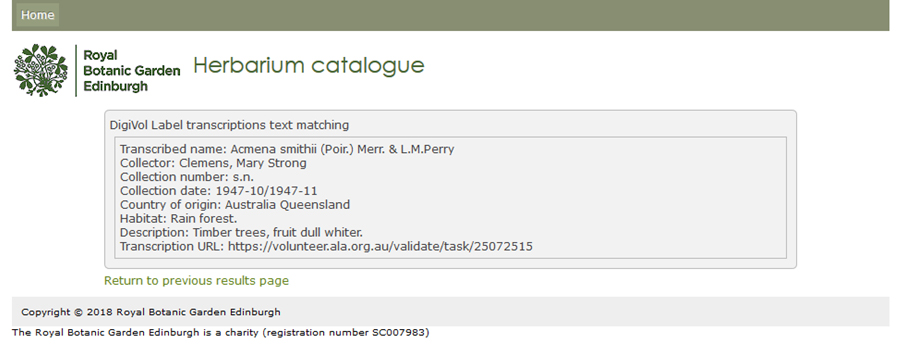

Searchable label data accessible to all

As we were gaining a large volume of good quality data through the transcriptions the volunteers were providing we worked to find ways to include this information in our online catalogue, as at present we are unable to include these data with our main collections data. These transcribed records sit in a separate database and are presented in a separate tab alongside the records from our collections database. These records can be searched, so it allows this data to be available to those who need it.

http://data.rbge.org.uk/herb/E00820331

We are now working on developing further citizen science projects, with plans to launch new expeditions on DigiVol soon. You can join us here:

Martin Ryman

I loved being part of this project – it combined my passionate love of plants, geography and history. Somedays I would cruise through and do many specimens, other days I would linger over a specimen and just enjoy its individual story – and each plant had its own story. One day I had the great thrill of transcribing the data from a specimen collected by Solander during Cook’s visit to Botany Bay in 1770. The herbarium specimens took me all over the continent, through time and different ecosystems, and introduced me to passionate plant collectors from the past. I was never the volunteer with the most transcriptions on an expedition, but I made sure I had fun on the way.

Sally King

Hi Martin,

Thank you for your lovely comment. It’s wonderful to receive such positive feedback from our online community of volunteers!

Best wishes,

Sally

Herbarium Volunteer Coordinator