A recently described moss, Sphagnum divinum, the Divine Bog-moss, has been discovered in Britain and Ireland, though the only Scottish site yet found has sadly been lost. Its taxonomic discovery has a long history, starting over 250 years ago with a French explorer in southern South America.

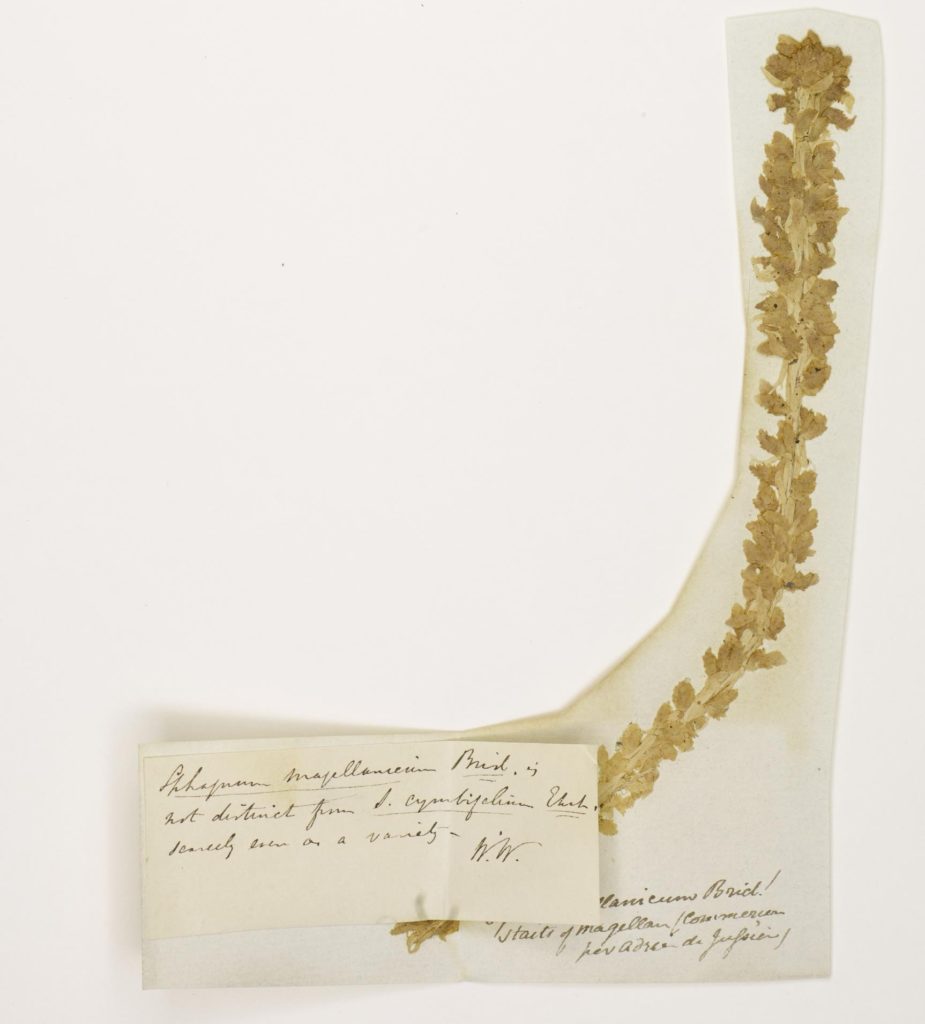

In 1766 the French navigator Louis-Antoine de Bougainville (1729−1811), was commissioned by the French government to circle the earth in a 3-year voyage of exploration. He was accompanied by Philibert Commerson (1727−1773), recruited as expedition naturalist. He in turn was accompanied by his partner and nurse Jeanne Baré – disguised as a man. In December 1767 their ship (the Boudeuse) reached the Straits of Magellan in southern South America where Commerson went ashore to collect. Duplicates of at least 3 of his new mosses collected there are preserved in the RBGE herbarium, namely Dendroligotrichum dendroides (Hedw.) Broth., Polytrichadelphus magellanicus (Hedw.) Mitt., and thirdly a Sphagnum moss described as Sphagnum magellanicum Brid. by the Swiss-German bryologist Samuel Elisée Bridel-Brideri in 1798. A recent study by Norwegian Sphagnologists and collaborators1 selected the Edinburgh duplicate of Commerson’s Sphagnum as the ‘lectotype’ for the species as no other duplicates could be found. Commerson’s specimens from 1767 are the oldest localised and dated bryophyte specimens found so far in the RBGE herbarium.

How did Commerson’s specimens come to be in Edinburgh? The annotations indicate that they came to us from the Glasgow University Herbarium when the cryptogamic collections were transferred to RBGE in 2005, and that they were in the herbarium of George Arnott Walker Arnott (1799−1868), one of a distinguished trio of cryptogamic botanists based in Scotland in the early 19th Century, along with William Jackson Hooker and Robert Kaye Greville. 2Arnott in his pursuit of bryology spent several years in Paris where he became fluent in French and acquainted with prominent French botanists of the time, particularly Antoine Laurent de Jussieu (who he called “old Jussieu”) and his son Adrien-Henri de Jussieu. The father had studied some of the plants brought back by Commerson from his voyage, and indeed validated the description in 1789 of the well-known genus Bougainvillea whose name had been coined by Commerson in honour of his captain. From the annotation on Arnott’s specimens, it was the son Adrien-Henri who gave Arnott duplicate bryophyte specimens from his collection and these, now in Edinburgh, remain fertile ground for future research. For example, they include duplicate specimens collected by Alexander von Humboldt in South America and from the very important herbarium of Ambroise Marie François Joseph Palisot de Beauvois.

In February 2003 I was fortunate to visit the Ushuaia region in the Argentinian part of Tierra del Fuego, on a botanical expedition with Pete Hollingsworth of RBGE and Keith Watson of the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, Glasgow. We found Sphagnum magellanicum to be a quite common and conspicuous moss, forming extensive deep red cushions on open heaths inland from Ushuaia. It looked very different from its appearance and ecology in Scotland where it forms relatively small red patches in wet hollows in raised bogs.

It therefore came as no surprise when our Norwegian colleagues 1Kristian Hassel and Kjell Flatberg along with their collaborators demonstrated, using DNA sequence data, that the material from Tierra del Fuego was a species distinct from what in the northern hemisphere had been called S. magellanicum in the past. In their new study Sphagnum magellanicum was split into three species − the ‘true’ S. magellanicum Brid. restricted to southern South America, S. medium Limpr. widespread in Europe and North America, including the British Isles and a new species S. divinum Flatberg & Hassel, also widespread in northern Europe, northern Asia, Japan and North America, but not reported from the British Isles. In response to this study, Mark Hill, our leading British Sphagnologist, has studied a range of British ‘S. magellanicum’ specimens, some from the Edinburgh herbarium, and found that most were S. medium, but seven were S. divinum, confirmed by him from Caernarvonshire and Flintshire in North Wales, Derbyshire and Northumberland in England, Berwickshire in SE Scotland and County Meath and County Wicklow in Ireland – an addition to the 35 species of Sphagnum previously known from Britain and Ireland.

The only Scottish specimen found so far (D.G. Long 28548) was collected at Penmanshiel Moss in eastern Berwickshire in 1999 where it grew in peaty hollows on the edge of a former raised bog, but on returning to this site recently I found the habitat had been lost to forestry activities and a wind farm, with no sign of the moss. However, it is very likely that further study will reveal more Scottish localities for this species. Penmanshiel Moss is probably now damaged beyond repair, but its fate is evidence of the importance of the current 3’Peatland Action’ programme supporting restoration of the many damaged peatlands in Scotland. At last the importance of this habitat and its component plants in locking up vast amounts of carbon is being fully recognised, and further exploitation and destruction of our precious peatlands should be strongly discouraged.

References

1 Hassel, K., Kyrkjeeide, M.O., Yousefi, N., Prestø, T., Stenøien, H.K. , Shaw, A.J. & Flatberg, K.I. 2018. Sphagnum divinum (sp.nov.) and S. medium Limpr. and their relationship to S. magellanicum Brid. Journal of Bryology 40: 197−222.

2 Cleghorn, H. 1868. Biographical notice of the late Dr. Walker-Arnott. Transactions of the Botanical Society of Edinburgh 9: 414−426.

3 https://www.nature.scot/climate-change/taking-action/peatland-action

Tim Rowe

Hello. I read your article with interest. In particular I note that the Berwickshire in Scotland has been lost. I have been researching landscape colours local to Scottish clan seats to see if there is a correlation between the landscape and tartan colours.

In my research I took photographs of striking pink and red mosses that may be of interest to you. unfortunately I cannot attach the photos.

Tim Rowe