The Scottish Rare Plant Programme is a collaborative project between the Science and Horticulture divisions here at RBGE. Our aim is to identify the ways that we as a botanic garden with the unique mix of resources and skills that we have, can work towards the conservation of Scottish biodiversity. One of our key activities is to work intensively on specific threatened Scottish species, such as Woolly Willow (Salix lanata), Alpine Blue-sow-thistle (Cicerbita alpina), and Small Cow-wheat (Melampyrum sylvaticum), by increasing their numbers within their natural habitats in a way which is backed by research and then carefully monitored. We also maintain a much larger number of rare Scottish plants as ex-situ conservation collections within the four gardens of RBGE and elsewhere, a project instigated initially in response to Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation (2002-2020). Finally, we aim to explore ways in which Scottish plants can be used effectively within gardens to, amongst other things, mitigate the impacts of climate change, support biodiversity, and improve wellbeing and enjoyment within garden spaces.

2020 has brought many challenges to the project, but we were also lucky that it brought some blessings too, one of which was that we were able to host an intern from the Robertson Trust Internship program this summer. Krissy Stevenson joined us throughout August and got stuck into the whole broad range of tasks that conservation horticulture encompasses, bringing her sunny disposition and faultless work ethic to each task. Here she shares an inside glimpse into her time with us behind the scenes of conservation horticulture of Scottish native plants here at RBGE:

My name is Krissy and I’m going into my 4th year of studying Environmental Science at the University of Stirling. I am a Robertson Trust scholar, which is a charity that helps young people with finding their feet at University as well as finding the right path going forwards. It was the trust that found me this internship and I was so excited when I found out that I’d get to see the behind the scenes of the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. I had visited the garden prior to my internship and found it absolutely incredible and beautiful. I was also mystified as to how they grow and maintain the many plants within the garden. By doing this internship I quickly learned how much time, knowledge, and care goes into each plant that may one day find its way to the gardens.

Scottish Native Plant Horticulture

My internship was based in the nursery where the plants are grown. I worked with Martine Borge who is the Scottish Native Plant Horticulturist and I found her work really interesting. The nursery has different tunnels filled with all kinds of plants and Martine’s was filled with plants native to Scotland! She has many Cicerbita alpina, known as Alpine Blue-sow-thistle. It is a really pretty plant found in only 4 sites across the Cairngorms. Sadly, their population has declined to the brink of extinction, largely due to herbivores grazing on them, amongst other factors. The four remaining populations are found in steep gullies and on inaccessible ledges where they cannot be reached by grazing animals. The garden is in the process of translocating them back into the wild and monitoring their growth and survival. The genetic health of the populations is also being researched and that information is used to ensure the best chances for the translocations. These lovely plants can be seen in the Rain Garden, Rock Garden and Demonstration Garden at RBGE as well as at Dawyck and Benmore botanic gardens! At the nursery I had a few tasks that involved the care of these plants, including cutting back the flowers to stop them from cross pollinating and mixing up the genetics, as well as spraying them with SB Plant Invigorator to help to manage the powdery mildew that was growing on a few of them.

Biosecurity

Biosecurity is very important at RBGE. The garden has many measures in place to limit the spread of pathogens to habitats via plants, which can be a big threat to biodiversity. One biosecurity task I did a few times was to give plants a bubble bath in SB Plant Invigorator! I thought this task was so cute but the reasons behind it weren’t. I had to do this for the rare Scottish Woolly Willow (Salix lanata), I re-potted, as I discovered root woolly aphid that can affect the roots and weaken the plant making it more susceptible to other diseases. I was surprised at all the biosecurity measures in place to ensure that their plants are kept healthy. Shoes need to be cleaned in disinfectant foot baths on entrance to the nursery and each tunnel, all plants, containers, and compost are kept up off the floor at all times, and pots and other equipment are sterilised between uses. Plant material entering the nursery is kept in isolation for 6 months and inspected by the Plant Health Officer before it can enter the main nursery. Plants leaving the garden are also inspected thoroughly. This is particularly important with plants going into the wild as part of the Scottish Rare Plant Programme. Something that I never expected was for the biosecurity to be so strict that plants throughout the nursery and garden are regularly inspected and sometimes a plant might be incinerated, if certain pathogens are found, to ensure that no other plants can also become infected or infested.

Scottish Plants in the Garden

In the garden there is an area that is prone to flooding which has been turned into the Rain Garden in a collaboration between RBGE and Heriott Watt University. The soil has been amended so that it can absorb large volumes of water in wet weather, showing how sustainable garden design can help to mitigate impacts such as flooding resulting from climate change. This is an experimental garden where many different plants are being tried for suitability for this kind of design, including Scottish native plants. I re-potted some Scottish native plants that are going to be trialled within the Rain Garden, as well as many plants which are to be planted in the Demonstration garden meadow, which is also being developed at the moment. This shows how Scottish native plants can be used in different garden areas, giving ornamental and environmental value.

Yarrow (Achillea millefolium) and Scots Lovage (Ligusticum scoticum) being put into bigger pots so they can grow bigger for the garden

Conservation Horticulture and Plant Records

To me, the key differences between conservation horticulture and normal horticulture is the actions taken after a plant has found its way to its final destination. A normal horticulturist would still look after the plant, but a conservation horticulturist might monitor the plant carefully, e.g. take data and information from the plant, for research and conservation purposes. Martine and her colleague Dr Aline Finger returned to sites where Cicerbita alpina plants had been translocated to monitor their growth, flowering, and how effected by grazing animals they are. This is very important as it will help Martine to see what conditions and methods work best for successfully translocating them, and getting data to show what the biggest threats are to them in the wild. On my last day of my internship I helped Martine monitor the Cicerbita that can be found in the gardens, so they can be compared to the ones translocated in the wild. The Cicerbita in the gardens are at a lower altitude, in a milder climate, than the wild plants, with no grazing animals to eat them. We measured the height and width and general fitness of the plants, and also looked at how effected they were by competition, sun exposure and slug damage. Although the flowers were beginning to die, this was one of my favourite activities as I loved seeing the Cicerbita in the gardens growing tall. Some of them had even grown taller than me!

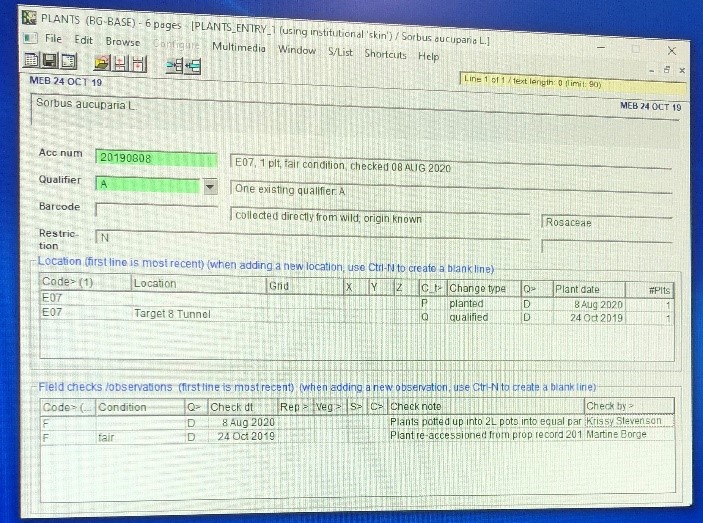

After the monitoring I got to use the garden’s database that stores all the information on every plant within the nursery and gardens. A number and code is given to every single plant that is grown. All this data is found within a database where every change made to the plant can be updated, i.e. when it is re-potted into a larger pot at the nursery and where it can be found i.e. a specific tunnel or which part of the gardens it is in. I got to update this system for plants that I had potted up and for the Cicerbita that were in the Rain Garden. I thought it was so cool that if I needed to, I could look up the history of plants from so many years ago. I was also so excited that my name was now on the database!

A screenshot of the database as I was updating it

Before I started my internship, I wasn’t sure what to expect. My school and University have given me a lot of experience for working in the field accessing physical geography, but I’d never had professional experience with horticulture. Many older generations in my family loved taking care of their gardens, so I think from a young age it has always been something I’ve wanted to gain experience in. I was surprised by the amount of plants growing in the nursery and the amount of biosecurity measures in place. I didn’t expect to find the whole experience so relaxing. The potting up of plants was very therapeutic to me and I really enjoyed taking my time to ensure I gave each plant the right amount of effort. Also, the internship gave me such a positive attitude towards my future. For years now I’ve known I want to have a career in conservation after University, but I was always slightly worried about what path I’d take. I find the work being done at the gardens and the nursery very inspiring. As conservation is such an interest of mine, I found it fascinating that the nursery acts almost as a zoo for plants, where really rare plants you’d probably never see in the wild can be found there. The garden has also been working towards Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation, with advises that at least 75% of threatened plants in any given country should be held in ex situ collections, i.e. botanical gardens, and at least 20% should be ready for recovery and restoration projects. I really am hopeful that I can be a part of work like this in the further and help conserve our native plants. Typically, when people think of our highlands, they maybe would expect them to be very biodiverse. Sadly, grazing and other problems have negatively affected our plant biodiversity. Hopefully with the work of the gardens and other organisations our land can become more healthy and colourful again! I will now strongly encourage people to add native plants into their own gardens and to reconnect with nature as it will not only benefit our wellbeing but will also be so beneficial to our ecosystems.

On one of my last afternoons I had a fun little task to create shade for Chickweed Wintergreen (Lysimachia europaea) that were getting too much sun. I thought the result was very cute!