The visitor

On the 17th of November 1874 an elderly working weaver – ‘compelled in his destitution’ – applied for poor relief in the Aberdeenshire parish of Alford. At that point the man’s average income was two shillings a week: the equivalent of around £60 in 2020.

In late 1839 the same man had made a week long visit to the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh where his closest friend was one of the foreman gardeners.

And, curiously, sitting on a shelf in the Rare Books Room of the RBGE Library is a well-worn copy of a book previously owned by this man.

The man’s name was John Duncan and in this ‘Botanics Story’ you will learn something about his life and friends, and his visit to RBGE.

In a follow-up ‘Botanics Story‘ you will find out about John’s book collecting and studies, and the book held in the RBGE Library.

The narrator

We know about John’s life, because William Jolly, one of Her Majesty’s Inspectors of Schools, got to know him in his later life and passed on his story to a wide audience, firstly in the religious magazine Good Words, and most importantly in a biography published in 1883 – two years after John’s death – called The Life of John Duncan, Scotch weaver and botanist: with sketches of his friends and notices of his times.

This means that John’s story is narrated through Jolly, and whilst Jolly tells John’s story sympathetically, from time to time he lets his prejudices intrude, and perhaps recounts events in John’s life that he might have omitted if he had been writing the life story of a fellow professional. On the other hand, Jolly gathered recollections of John from the people who knew him, and the use of these throughout the biography, gives it a certain vividness, particularly when Jolly tries to reproduce the local Scots dialect used by John and his friends.

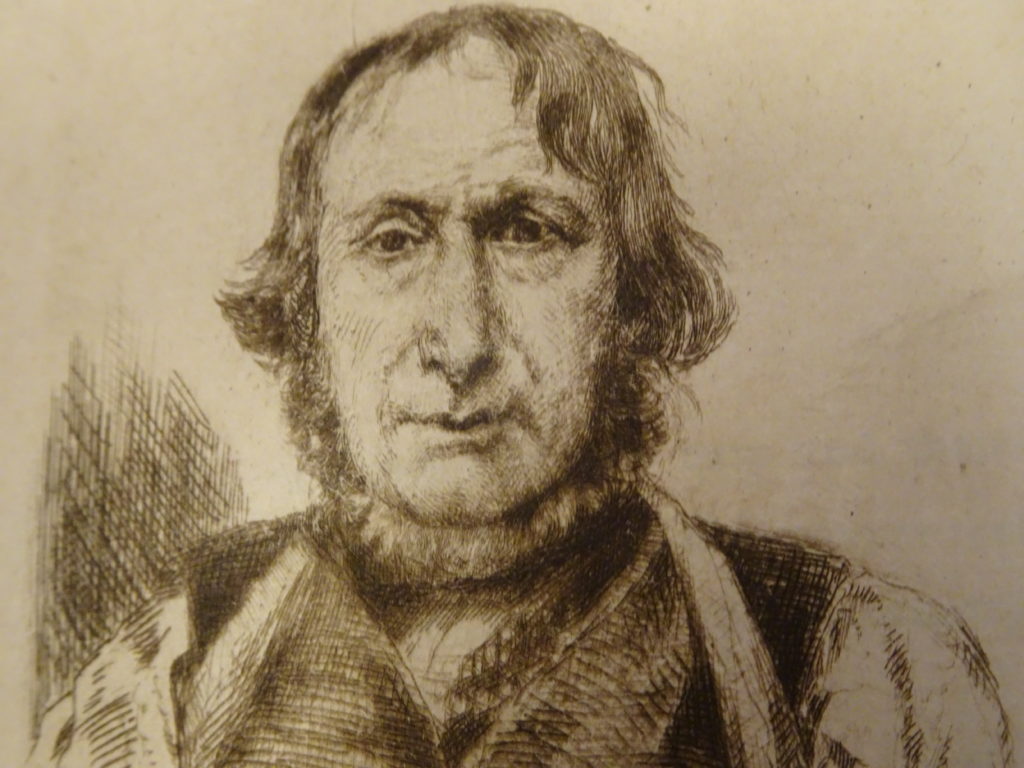

Here is what John looked liked in 1866 when he was aged 72. The engraving is done from a photograph taken in Aberdeen and it was used as the frontispiece to Jolly’s biography.

Jolly certainly helped John in his last year, as he was a driving force behind a movement to establish a subscription fund to provide John with financial assistance. The fund was widely promoted, with Jolly even using the pages of Nature to communicate John’s story to potential subscribers. Queen Victoria, Charles Darwin and the employees of the Addiewell Chemical Works, were amongst the donors to the fund. As a substantial sum of money was gathered it was put into a Trust, which was used chiefly for educational work in the Alford area, as well as providing John with a pension.

Jolly’s earlier articles in Good Words also spurred well-wishers to assist John with presents of money and goods.

John’s life

John was born near Stonehaven harbour in December 1794. His mother Ann Caird, had been deserted by John’s father, a weaver, from her home village of Drumlithie.

John received no official schooling. Whilst serving his apprenticeship as a linen weaver in Drumlithie, Margaret Pirie, his master’s wife, taught him to read. Jolly notes that Mrs. Pirie was well-read with a collection of books above the norm for a woman of her social position.

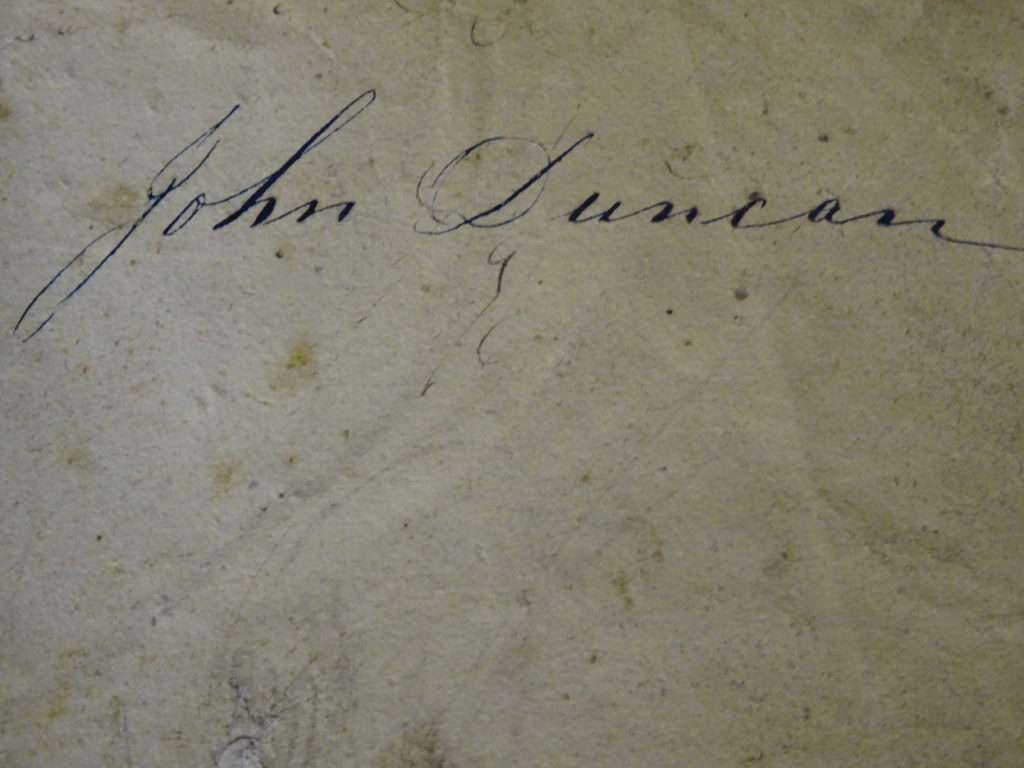

John did not learn to write until he was over thirty. Jolly, always the teacher, comments on his penmanship. Here is John’s signature from the book in the RBGE Library.

During his apprenticeship John began to study medical botany using an edition of Nicholas Culpeper’s Complete Herbal as a guide.

John was working as a linen weaver in Aberdeen factories, when he married Margaret Wise. They had two daughters. The marriage was an unhappy one and John and Margaret separated. John also learned woollen weaving whilst in Aberdeen.

In 1824 John moved from Aberdeen to become a country weaver, near Monymusk.

From 1823-1833 John lived at Auchleven, where he worked as a weaver in the carding mill. Here John developed an interest in astronomy, which caused some of his neighbours to give him the nickname ‘Johnnie Meen’ [Johnnie Moon].

He settled at Netherton near Alford in 1836. Here he lived a simple life working as a weaver to Peter Marnock, and collecting plants.

In 1849 he returned to Auchleven where he stayed for some years. During this time he held an exhibition of his herbarium specimens in the carding mill loft, and read a few essays at the local Mutual Instruction Class.

In 1852 John returned to the Alford area and settled at Droughsburn. Here he worked at his loom and cultivated an unusual garden of wild and medicinal plants, which he used for teaching and healing.

John died at Droughsburn on 9th August 1881 and he was buried in Alford kirkyard on the 15th August. In accordance with John’s wishes friends laid a rough stone on the grave. Some of the money gathered by subscription for John was used to erect a granite monument decorated with a carving of the twinflower, Linnaea borealis, at the head of the grave.

Charles Black (1813-1890)

‘All his days, [John] made a point of gaining the friendship of gardeners wherever he went. They worked among the plants he now increasingly loved; they also furnished him the means of obtaining herbs not indigenous to Britain, but required in his widening pharmacopoeia’ [Jolly (1883), page 84.]

Charles Black entered John’s story in the spring of 1836. At that time Charles had served almost two years as gardener at Whitehouse, a mansion close by Netherton. John was introduced to Charles through Willie Mortimer, the Netherton shoemaker. Charles had been a farm worker, when Willie knew him first.

Until meeting Charles John had been mainly studying plants to gain knowledge of their medicinal uses. The friendship between the two developed as Charles taught John systematic botany and John began to create his own collection of preserved plants. Many of John’s herbarium specimens were kept in wrappers made from the Aberdeen Constitutional, a Tory supporting newspaper. John was a Liberal and clubbed together with friends to read the Aberdeen Banner. Charles was a Tory supporter. Charles and John made botanical excursions in the area, On one of these rambles Charles lost his copy of Dickie’s Flora Abredonensis. The kitchen at Whitehouse was used as workroom to prepare specimens for their herbaria, much to the annoyance of the housekeeper.

Charles left Whitehouse in 1838.

Here is an outline of Charles’s working life as far as it can be gleaned from Jolly, and online newspaper sources. It is a typical example of the horticultural career, of a gardener who received training at RBGE in the early Victorian period.

- 1813. Born at Mains of Pitcaple, Chapel of Garioch parish, Aberdeenshire, 1st July.

- -1826. Attended school until age 13.

- 1826-1832. Worked as a herd boy and then as a farm worker until age 19.

- 1832-1834. Apprentice gardener at Cluny Castle from age 19 to 21.

- 1835-1838. Gardener at Whitehouse, parish of Alford, from age 21 to 24.

- July 1838. Marries Ann Gall, lady’s maid at Whitehouse.

- 1838-1840. Journeyman gardener at RBGE : wages ten shillings a week.

- 1840-May 1842. Gardener at Whitehouse, parish of Alford.

- 1842. Foreman in Reid’s Nursery, Aberdeen.

- 1842-1848. Gardener at Raeden, near Aberdeen.

- 1848-1849. Gardener at Leith Hall, Kennethmont, Aberdeenshire.

- 1849-1858. Gardener at Hamilton Palace, where one of his brother’s was head gardener.

- 1858-1864. Gardener at an unidentified house near Dalry, Ayrshire.

- 1864-1888. Gardener at Arbigland, Kirkcudbrightshire.

- 1890. Died at Dumfries in December.

John Duncan and ‘field’ botany

John collected plants over a wide part of Aberdeenshire and neighbouring counties. He also collected in other areas of Scotland, mainly in the east but also around Glasgow and into Renfrewshire. Botanising in these areas was possible because of John’s practice of working as an itinerant harvest labourer. Teams of men and women working at other occupations, hired themselves in the late summer and early autumn to help with harvesting. John continued to hire himself in this way until he was seventy.

He had come supplied with home-made books, formed of newspapers and grocers’ tea-paper, to press and preserve the plants in. These he kept carefully protected in the big bundle containing his clothes.

JOLLY, (1883), PAGE 228

‘All his spare time was spent in exploring the neighbourhood for plants. In this work he had many willing or curious assistants in his companions and in the farmer himself, who brought him all the plants they could lay their hands on. He counted petals and stamens and told their names, preserving all the rarer specimens for his herbarium. It was a picturesque and interesting sight to see these groups of amateur botanists gathered around the little man after the labours of the day… while many a merry laugh was raised at the grand, jaw-breaking names the common weeds that grew in the ditches and hedges were dignified with, in their eyes.’ [Jolly (1883), page 228.]

Certainly, in this case, a field botanist supported by field work.

Parts of the John’s herbarium were donated to Marischal College, University of Aberdeen in December 1880. John Taylor – who had received his earliest lessons in botany from John – spent time adding localities to the herbarium specimens before they were transferred. John had not added collection localities when preparing his herbarium specimens, but rather depended on his memory to recall where particular plants had been collected.

The visit to RBGE

Here is Jolly’s account of John’s visit to RBGE, with some explanatory notes.

In 1839, the year after Charles had settled there, John Duncan paid him [Charles Black] a long-anticipated visit, going there from Dundee, where he had been harvesting. This was not the first time, however, that he had stayed in the capital, for he had been there before when he went through the Lothians to the harvest. Far, far above all the lions of the town, interesting as Edinburgh is in sights and memories to stir the heart of every Scotchman, especially a patriot like John, was the garden down in Inverleith Row, known as the Royal Botanic. During all the time he was in town, John spent the whole or chief part of the day in that enchanted land, in Edenic felicity, from early morn till dewy eve. Sometimes he did not even take time to go home with Charles for his food, bringing with him his old bag of oatmeal, which, in more primitive simplicity than the oldest gardener and his wife no doubt indulged, he ate with relish, moistened with water and sweetened with appetite. If the reader should imagine that John Duncan had no pride of appearance, judging from his odd, old-fashioned dress, he would be mistaken, for he was most particular regarding his personal looks and tidiness in clothes. Thinking his own home-made attire not fine enough for such an important occasion, he donned Charles's long-tailed surtout and vest, to look more, as he deemed it, like the time and place. In this change of apparel, he was, no doubt, quietly backed by Charles himself, for he wished the ancient-looking weaver, as became a friend of his, to appear as like other people as possible. Saturday was the only free time for the public, but Charles obtained leave for John to enter every day, under his care. He showed him round the whole garden, with no small pride and with mutual pleasure. John's surprise and delight were expressed in child-like phrase, as each new point of beauty and interest met his view. He was taken into the various hothouses, where he saw plants he had never seen before, though he had visited every gardener he knew in the north. He entered the great palm houses, where he first gained a practical realisation of the gigantic and luxuriant vegetation of the tropics. The sensitive plant (Mimosa sensitivd), seen for the first time, specially drew his notice and fixed itself in his memory. He was also greatly surprised at the remarkable size of the leaves of some of the palm trees. Seeing a leaf of special expansiveness from the gallery above it, he remarked to his friend, "Man, Chairlie, ye cu'd be rowed inside that, like a pund o' butter in a doken!" He also was silently impressed when he was privileged to see and consult the large herbarium gathered by the professor and students, from which he took many a note, and on the plan of which he tried to frame his own in after years. He also followed the students, as they listened to the discourses of Professor Graham, and moved about amongst the plants while he explained the peculiarities of each flower on the spot; making John think how happy they were to have such opportunities, which he, poor man, never had enjoyed. Would that more of the young men that pass through this admirable practical course, would cherish a little more of the old botanist's feelings! He was also deeply moved at seeing the monument erected in the gardens to his great master, Linnaeus, mentioning his visits to see it with special emphasis; for the famous Swede was one of his greatest men, and he never mentioned his name but with the profoundest respect and reverence. He knew his life minutely, and used to tell stories about him in capital Scotch, with ecstatic, friendly detail, as if he knew and loved him with a personal affection. One of his most cherished possessions was a portrait of Linnaeus, afterwards sent him by a friend as an expression of respect. But the part of the garden in which John spent the most of his time was the British section, where the plants were classified according to the Linnaean system, and grew in plots, with their orders, species, and names attached. These were, to a keen amateur like him, the Elysian fields themselves. There John spent many charmed hours. From his short-sightedness, he was obliged to kneel on the grass and stretch far over into the plots to see the names. Being shy and fearful of offence, he could not think of taking the liberty of lifting the labels in his hand, reading and carefully replacing them, as most men would have done. Stepping on the cultivated ground being forbidden, and his curiosity about the names demanding satisfaction at all hazards, he would look furtively round before venturing to peer so closely at the painted tickets, in order to see if anyone was observing him; then cautiously step into the plot to read them; and then religiously rearrange the earth where his foot had left its print. He was observed doing this by the head gardener, Lawson, who knew him as Black's friend and an ardent botanist. Lawson told Charles, out of kindness to John, to go to him and say that "if he wasn't a thief, he shouldn't look so damned thief-like!" but boldly lift the labels and replace them ; as the director might be walking about, and might misunderstand his movements. By that time, having gained considerable practical power over the science, John knew enough to be able to direct his attention profitably to the parts new to him, and benefited greatly by the days he spent in the Botanic Gardens. As he said afterwards, "In Edinburgh, I was gae expert aboot the plants, I can tell you;" for his self-esteem was never very latent, bashful as he looked. "Ay, ay, I had my e'en a' aboot me there!" and there was not the slightest doubt that he had ; for his short sight served him better than the long sight of most of us. Jolly (1883), pages 183-187. NOTES 'He entered the great palm houses' : RBGE's oldest surviving glasshouse [currently known as the Tropical Palm House] opened in 1834, to provide much needed space for cultivating palms. "ye cu'd be rowed inside that, like a pund o' butter in a doken!" : you could be rolled up inside that, like a pound of butter inside a dock-leaf. George Johnston in his 'Botany of the Eastern Borders' (1853) notes that dock leafs were used in that area to protect butter from the sun when transported for sale in local markets. [Johnston, (1853), page 174.] 'consult the large herbarium gathered by the professor and students' : In the late eighteenth century Professor John Hope started to award prizes to his students for their collections of preserved plants. This scheme continued well into the following century. The University Herbarium at this time was housed at the Old College. 'listened to the discourses of Professor Graham, and moved about amongst the plants while he explained the peculiarities of each flower on the spot' : Here John experienced a teaching method which has been a constant feature of RBGE from its earliest days. 'a portrait of Linnaeus, afterwards sent him by a friend' : This is most probably an engraved portrait which Charles Black sent to John in 1866, as a gift from James Linn. [Jolly, (1883), page 323.] 'the British section' : Some of the plants grown in this section had been collected by RBGE gardeners, including Charles Black himself. 'the head gardener, Lawson' : When John visited RBGE the Principal Gardener/Curator was William McNab (1780-1848), and one of the main nursery and seed companies in Edinburgh at that time was Peter Lawson & Son. Given the intervening years it is possible that John muddled the names when telling Jolly about the visit. That said, details about other gardeners working at RBGE in the 1830/40s are difficult to come by. Information about them comes mainly from secondary sources - like Jolly - and occasional references in RBGE administrative archives: so it may be that Lawson is an unidentified RBGE gardener. "In Edinburgh, I was gae expert aboot the plants, I can tell you;" : In Edinburgh, I was quite the plant expert. "Ay, ay, I had my e'en a' aboot me there!" : Certainly, I kept my eyes open and took everything in then.

Further reading

You can read a digital copy of Jolly’s biography of John via the Biodiversity Heritage Library. Here is the link: https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/17844