In the first of these Botanics Stories we introduced the weaver botanist John Duncan and his friend Charles Black. In this blogpost we give some details about John’s book collection and his studies. To finish we introduce the book from John’s collection that survives in the RBGE Library.

Why did John Duncan acquire books

Quite simply John acquired books to learn; and he acquired a noteworthy collection for a working weaver of limited means. His biographer, William Jolly writes:

‘He lived very simply, if not sparely, though healthily, in order to be able to obtain the tools for intellectual work – the much-coveted books.’ [Jolly (1883), page 50.]

‘A knowledge of the world in which he dwelt was necessary to his happiness, and he studied geography. He must become acquainted also with the strange and fascinating story of the doings of the human beings that have lived and died on its surface. He therefore devoured history and biography, both British and general, ancient an modern, and on both subjects he gradually gathered a large number of books..’ [Jolly (1883), page 88.]

‘But books he must have. The money spent on them might perhaps have made him richer in pocket, but it certainly would have rendered him poorer in thought and happiness, if not, with his hidden sorrows, a wreck. Which of us could have the heart to grudge him this one intellectual extravagance, saved, as it undoubtedly was, from stomach and back? [Jolly (1883), page 401.]

What was in John Duncan’s book collection

I hae a leebrary o my ain and what money I can spare will gae to increasing it; that’s my way.

john duncan, quoted in william Jolly’s life of john duncan

‘John’s appetite for general knowledge was still omnivorous and keen, and he had a host of books supplying for it healthy food.’ [Jolly (1883), page 302.]

Unfortunately, Jolly does not provide an itemised list of the books in John’s collection. However, working through the biography basic details of some of the the books and their subject matter can be pulled together. It would be good to find out if a list of the books was ever drawn up and retained somewhere after John’s death, as this would clear up currently unanswerable questions about editions and imprints.

General Reference

- Orr’s Belfast Almanack. All annual volumes published from 1815 to 1881.

- Knight, Charles. Natural history.

- Chambers’s. Information for the people.

- Chambers’s. Cyclopaedia.

- Dictionary of daily wants.

Languages

- The rudiments of the Latin tongue, or a plain and easy introduction to Latin grammar. Edinburgh. (1803)

- An abridgement of Ainsworth’s dictionary, English and Latin, for use in schools. (1825)

- Universal Etymological English Dictionary of N. Bailey. 17th edition. (1757)

- A dictionary of the Scottish language: founded upon that of John Jamieson: in which are shewn the various meanings and modes of spelling the same word.. Edinburgh. (1827)

- Grammar made easy. (1805)

Arithmetic

- Cockers’s arithmetic: being a plain and familiar method, suitable to the meanest capacity, for the full understanding of that comparable art,… Glasgow. (1787).

- Gray, James, (teacher at Dundee). An introduction to arithmetic. (? 1836) [Acquired in 1839]

Botany

- Galpin, On Botany. [? Galpine, John. A synoptical compend of British botany…arranged after the Linnean system, etc.]

- Lee, John. Introduction to Botany.

- Hooker, W.J. British Flora.

- Rattray, James. A botanical chart: or, Concise introduction to the Linnaean system of botany. (? 1835)

- Pinnock, W.H. Catechism of Botany.

- Dickie, George. Flora Abredonensis. (1838)

- Lindley, John. School botany and vegetable physiology. [John’s copy was a present from George Dickie, Professor of Botany, University of Aberdeen]

- The Common Seaweeds.

Medical Botany/Herbalism

- Culpeper. British Herbal.

- Rennie, James. Alphabet of Medical Botany. (1834)

- Hill, John. The family herbal.

- Tournefort, Joseph Pitton de [John Martyn, translator]. Compleat Herbal. (1719)

- Culpeper’s ‘Herbal’ edited by Sir John Hill. (1835)

Astronomy

- Levett, James. Astronomical and Geographical Lessons. (1814)

- Catechism of Astronomy.

Weaving

- Peddie, Alexander. The weaver’s assistant. (1817)

- Duncan, John. Practical and descriptive essays on the art of weaving. (1808)

- Murphy, John. A treatise on the art of weaving. Third edition. (1831)

History and Biography

- Roberts, George, (schoolmaster). A catechism of classical biography: or, The lives of illustrious poets, historians, orators, &c., of antiquity. London. (1824)

- The history of Scotland. 2 volumes.

Theology and Church History

- Henry, Matthew. A method for prayer.

- Henry, Matthew. Commentary on the Bible.

- Brown, John (Haddington). A dictionary of the Holy Bible.

- Stackhouse, Thomas. A history of the Holy Bible. 2 volumes.

- The popular Biblical educator. London: John Cassell. (1854-55)

- The plants and trees of Scripture. London: Religious Tract Society.

- Howie, John. Scots Worthies.

- The Cloud of Witnesses.

- Foxe, John. Book of martyrs.

- Buchanan, Robert. The ten years’ conflict: being the history of the disruption of the Church of Scotland.

‘He began also the Greek rudiments, in spite of its peculiar alphabet to bar the way of a home student. This great language he continued to study, chiefly in order to get at the original tongue of the New Testament’ [Jolly (1883), page 88.]

Astrology

- Bo, an Indian astrologer.

- A manual of astrology. (? 1828)

- The astrologer of the nineteenth century. (1825)

Where did John Duncan acquire his books

John either bought or was made presents of books. Jolly gives examples of John buying from booksellers, book barrows and auctions.

‘In Stonehaven, he began the formation of the large, well-selected, and, for the very poor man he always remained, costly library which he gradually accumulated, and the possession of which became one of his ruling passions.’ [Jolly (1883), page 50.]

The first book John bought was a copy of a modern edition of Culpeper’s ‘Herbal.’ Jolly says this about that first purchase:

‘He must have his own text-book, and after months of extra work, for wages were very low, he became at last the proud possessor of a copy of his own, which cost one pound’ [Jolly, (1883), page 50.]

‘…buy some desired volumes from the old book shops in Aberdeen, which he used regularly to frequent, and where he picked up many a rare volume and pamphlet.’ [Jolly (1883), page 71.]

‘The sight of books in the booksellers’ windows was a sore temptation to the weaver. In Edinburgh, however, he withstood it well, for he bought only one volume, on Botany, which he found on an old bookstall in the street.’ [Jolly (1883), page 189.]

‘the innkeeper accompanied a surviving son and his family to America, and, for some reason, all the books were sold. John Duncan was at the sale to watch the fate of the memorable volumes [Hooker’s British Flora], and, if possible, to rescue them from unappreciative hands; and they were knocked down to him for the large sum of – one shilling!’ [Jolly (1883), page 160.]

This copy of W. J. Hooker’s British Flora had belonged to George Davidson, who had served his gardener’s apprenticeship at Castle Forbes, and subsequently worked in England. Sadly he developed a terminal illness and came home to die. George’s father Willie kept an inn near Whitehouse, and retained his son’s books as a memorial. He was happy to allow John and his friend Charles Black to consult the books at the inn. In exchange John and Charles would buy a sixpenny dram each as a thank you.

Here are two references in Jolly to books received by John as presents:

‘He was presented with a copy of ‘The Common Seaweeds,’ but never had an opportunity as a man, of studying the branch of Botany, having lived far inland since he took to science’ [Jolly, 1878, page 389.]

‘This was the veritable ‘Rattray’s Botanical Chart’ which Charles Black had presented to him. He prized it accordingly, and showed it to me, with affectionate pride, as Charles’s last gift to him when they parted many years before.’ [Jolly, (1883), page 314.]

How did John Duncan look after his book collection

John protected his books by having some off them bound in strong bindings.

“‘Murphy on Weaving,’ a learned treastise with engravings, published in 1831, which he afterwards got strongly bound for regular use.” [Jolly (1883), page 85.]

Throughout his life John had to protect his books from pests and damp. One off his methods against the latter is perhaps a case of using a lesser evil to correct a problem. When living at Droughtsburn he kept some of his books in the jamb of the fireplace. This may explain the smoke stains on the book in the RBGE Library.

‘There also he kept many of his better books, for more ready reference and for protection from damp.’ [Jolly (1883, pages 243-244.]

Where did John Duncan keep his book collection

John’s living space was never expansive, and he does not seem to have had the luxury of bookshelves, apart from the jamb of the fireplace. Instead he stored his books in chests [Scots: kists]: a piece of furniture which every journeyman possessed to carry his worldly goods from place to place.

‘The most of his books and plants were kept in three large chests. The best of the books were carefully wrapped and tied up in several folds of paper. All the chests and plants and parcels were abundantly scented with camphor and died native plants, such as mint and woodruff, to preserve them from the insidious moth.’ [Jolly (1883), page 292.]

‘Key in hand, he opened one of the chests close by the door and revealed… a large number of books in very good condition. The under side of the lid exhibited the coloured pictures and printed matter he had pasted there to brighten the box and increase his pleasure when he consulted his library, herein partly contained.’ [Jolly (1883), page 387.]

How did John Duncan use his book collection

Without doubt John’s main reason for collecting books was to read them to gain useful and interesting knowledge. He really read his books, and reading was a slow process for John.

When John gave him [John Taylor] the loan of any book, he was accustomed to say, “Noo, Johnnie, lad, dinna be over weel-fashioned wi’t; be ill-fashioned. Look in atween the brods an see fat’s in’t. There’s some fowks sae weel-fashioned wi’ books that they never open them.”‘ [Jolly (1883), page 341.]

[After working as an agricultural labourer and prosecuting studies in natural science, John Taylor became assistant in the Public Library at Paisley. He wrote an account of his life as a farm servant, ‘Eleven Years at Farm Work’]

‘John’s own style of reading raised her [Mrs. Emslie’s] astonishment and respect, from his indomitable patience and determination to succeed. He had to spell all the longer words, and he read and re-read every sentence, accompanied by a running fire of “Ay, ay!” till he conquered both vocables and meaning. He used also to bring his books on Botany many of them with finely coloured plates, to show and explain them to his friends” [Jolly (1883), page 241.]

‘John…’mumbling and spelling’ at the book he was engaged on…As he read in an audible monotone, the listener could generally make out the subject. John went over the same sentence or passage again and again till he had mastered it’ [Jolly (1883), page 245.]

‘When he didna understand onything he just read it ower and ower till he had it.”

Charles hunter, SHOEMAKER, NETHERTON, ALFORD QUOTED IN WILLIAM JOLLY’S THE LIFE OF JOHN DUNCAN

‘John’s motto throughout life in all he did, from weaving to Biblical criticism and higher Botany, was, like that of all strong men, ‘Thorough.” [Jolly (1883), page 88.]

John did not keep his books to himself. He had a desire to share them with those who would appreciate reading them.

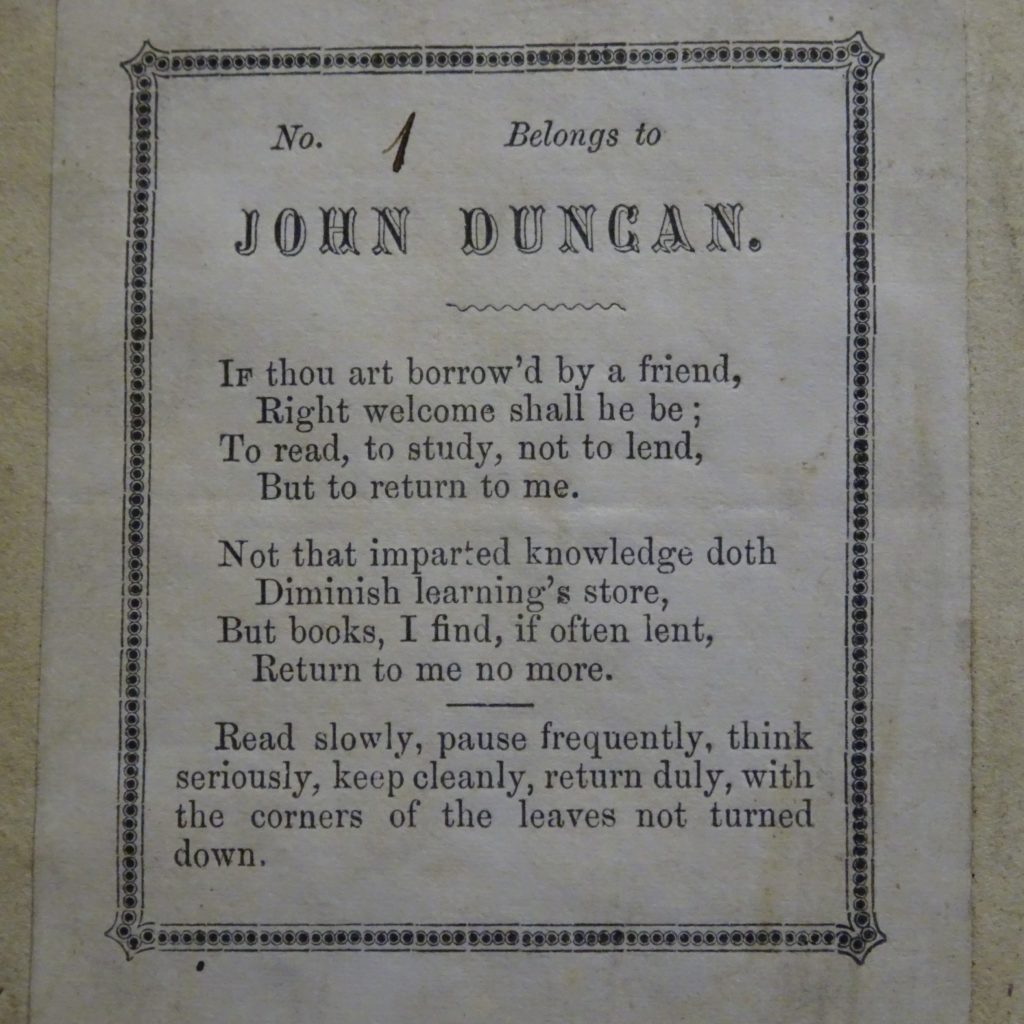

‘Though John’s care of his books was so great, his desire to spread knowledge was greater, and he used to lend them a good deal to his friends and the more intelligent of his neighbours; for nothing gave him more pleasure than to discourse about the subjects he studied with others, and assist them in prosecuting these in every way in his power. To prevent the loss of the books he lent, he got a small card printed at Netherton, which was pasted on each of them..’ [Jolly (1883), pages 292-293.]

‘John used also to lend his books on gardening to his friends at Cairnballoch [Mr. & Mrs. McCombie]’ [Jolly (1883), page 303.]

‘When any place was mentioned they did not know, John would consult his atlas at home and tell them about it at next visit, and sometimes bring down the book to point it out.’ [Jolly, (1883), page 291.]

‘He always took pains to see his books duly returned, and was not slack to remind any one when a book was kept too long.’ [Jolly (1883), page 293.]

The above image is taken from the book in the RBGE Library.

What happened to John Duncan’s book collection

During his lifetime John Duncan sometimes gifted books from his collection to friends. For example he gifted some books to John Taylor, when he worked over his herbarium, prior to its donation to Aberdeen University.

‘he was surprised and touched when the old man went to one of his chests, and taking his copy of Dickie’s ‘Flora,’ impressively handed it to him, in a way that conveyed more than his words, saying: “There, Johnnie, I’m to gee ye that. See that ye’ll get on noo.”‘ [Jolly (1883), pages 415-416.]

‘John also presented his friend with some other volumes in memory of the giver, saying, “I hae had my days o’ them,”‘ [Jolly (1883), page 418.]

‘He also sent two volumes as a last gift to James Taylor.’ [Jolly (1883), page 419.]

Jolly made his last visit to John during a period of heavy snows. On the first day of his visit John was very agitated and distressed. John was beginning to decline mentally by this time. After leaving John to rest, Jolly received a message through Peeny Allanach, the daughter of the neighbour who assisted John, asking Jolly to visit again. John apologised for his unkind words saying that he thought that Jolly was another man altogether ‘one who had stolen his books.’ It is difficult to say if there is any substance in this remark from an old man suffering from memory loss, but it may be someone had taken some of John’s books under false motives.

When the Trustees who managed the subscription fund raised for John’s support drew up the Trust deed they placed the following conditions for the future of John’s book collection in the deed:

‘It was further and generously enacted in the Trust Deed, that John Duncan’s large library of valuable scientific and other books should made over to the parish of Alford… and that their present custody be given to the Alford Mutual Improvement Society and after it ceases to exist, to the School Board of the parish; a few books only being reserved, to be presented by the trustees as souvenirs to intimate friends.’

Further investigation is needed to find out what happened to the books passed over to the parish of Alford.

The book owned by John Duncan now in the RBGE Library

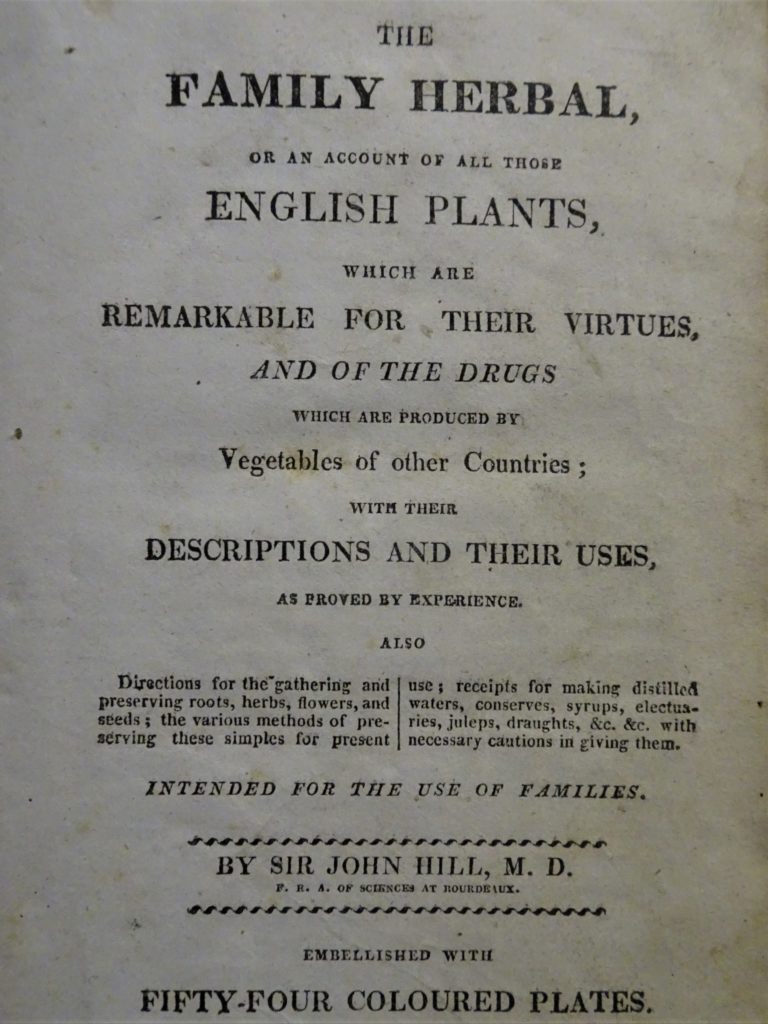

And what about the book in the RBGE Library? It is a copy of Sir John Hill’s Family Herbal published in 1812. Here is a picture of the title page:

And here is a picture of the leather title piece on the spine:

The book has been bound with a full leather spine and leather corners. One of the corners is damaged, but I’m not sure if it should be mended. You can see a picture of this damage earlier in this blogpost.

At present, it is not known how this book came to be in the RBGE Library. Perhaps it was one of the books given to John or James Taylor, or another of John’s friends, and they subsequently passed it to RBGE.

To conclude, here is a picture of the plate in the ‘Family Herbal’ showing Nymphaea alba. John almost drowned collecting a specimen of this plant from the Loch of Drum.

Truly a remarkable botanist and book collector. And this particular book is definitely not ‘stolen’ it is preserved in Scotland’s national botanical library.

Deborah Vaile

Thank you for bringing John Duncan alive to a wider audience. What an amazing man.

Best bits for me were;

Part 1 – “if he wasn’t a thief, he shouldn’t look so damned thief-like!”

Part 2 – to protect his books from damp ‘he kept some of his books in the jamb of the fireplace, which may explain the smoke stains on the book in the RBGE Library’