Intrigued by the recent Botanics Story concerning letters from the anatomist John Goodsir to his Edinburgh University professorial botanical colleague John Hutton Balfour, and involving their mutual friend Edward Forbes, I remembered that several years ago I acquired a Goodsir letter through some internet shopping. The reason was as a memento of any member of the Goodsir family for their friendship with their Fife neighbours the Cleghorns: at the time I was writing a biography of the pioneering Indian forest conservator Hugh Cleghorn. At the age of five, to avoid an infectious disease in his grandfather’s house of Stravithie, Cleghorn was sent to the care of Dr John Goodsir senior, the town surgeon of nearby Anstruther. Thus began a friendship with the future anatomist (then aged 9) and, in particular, with his brother Henry (‘Harry’), only nine months older than Cleghorn, who would perish as surgeon-naturalist on the Erebus during Sir John Franklin’s last and fatal Arctic expedition.

On its arrival a bonus was to find that the letter was addressed to the Edinburgh architect David Cousin (1809–1878). It was Cousin who designed what is now called the Caledonian Hall, originally the exhibition hall of the Caledonian Horticultural Society’s experimental garden, later subsumed into the Royal Botanic Garden. He also designed the West End church of St Thomas for a congregation that seceded to the Church of England from the Scottish Episcopal Church, now secularised as the Ghillie Dhu cocktail bar. This was Balfour’s church, a curious Janus-faced building: its Rutland Street façade incorporated into a Neo-classical terrace by means of a curious hybrid of Renaissance and Norman styles; its Shandwick Place face a Neo-Norman, double-gabled, fantasy of interlaced blind arcading and a Kilpeck doorway.

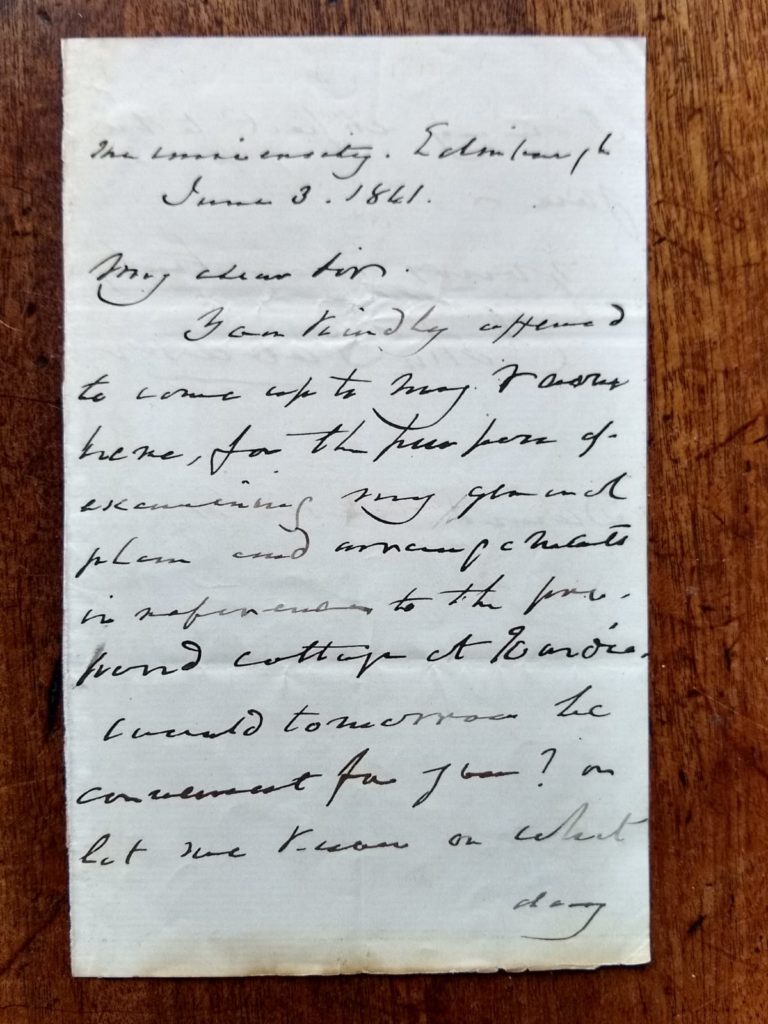

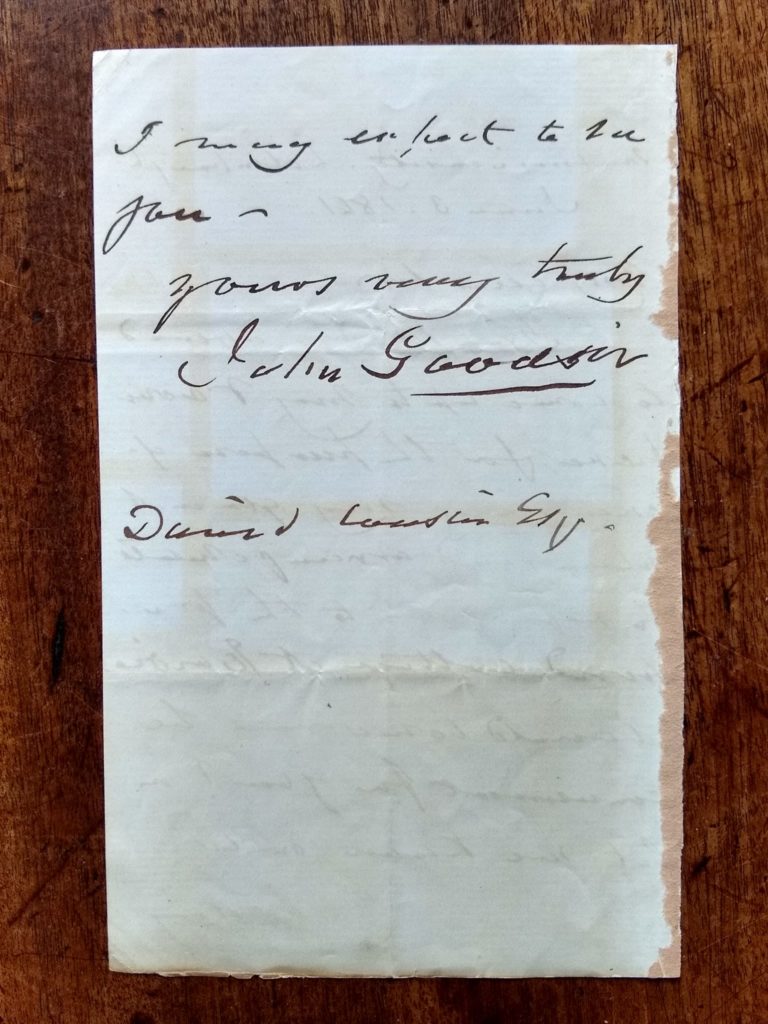

The note, for it is no more (twenty lines, including the address), concerns the setting up of a meeting between anatomist and architect about plans for a ‘proposed cottage at Wardie’. I had started to look into its background on several previous occasions, but given up on encountering a string of inconsistencies and erroneous information on the internet. These concerned nearly every aspect of the background to the personnel, buildings and dates involved. There turned out to be a problem even with the date of the letter, written in Goodsir’s crabbed scrawl. Addressed from ‘The University’ this looks, for all the world, like ‘June 3, 1841’. However, I discovered that Goodsir was at this date not employed by the University, but by the Royal College of Surgeons (as its Curator), so couldn’t have used it. From 1845 until his death in 1867 Goodsir seems to have had an aversion to providing his address to the annual Post Office directories, but in 1841 he was certainly still living at the famous flat at 21 Lothian Street formerly occupied by Charles Darwin during his unsatisfactory stay in the city. It took some time to realise that the date must be 1861: the right-hand loop of the 6 missing, its left part resembling the cross-stroke of a 4. Subsequent problems came with identifying the building referred to and the history of the fascinating set of people who inhabited the various houses along what is now Boswall Road, most notably the naturalist Edward Forbes, who died in South Cottage, Wardie in 1854, the same house in which Goodsir would die 13 years later.

Wardie Bay, with its fascinating geology and fauna, is a favourite destination for walks and I often divert along Boswall Road to look at these houses and ponder on their former inhabitants. At the top of the sixty-five-foot raised beach the grandest of these was built around 1830 as Wardie Lodge for John Hope’s son, the chemist Thomas Charles Hope. With an imposing, tetrastyle, pedimented portico it has never been attributed to William Henry Playfair, but I think it likely. Its grounds were developed in the second half of the nineteenth century by the builder’s niece, the garden writer, Frances Jane ‘Fanny’ Hope. Renamed Challenger Lodge it became, under Wyville Thomson and James Murray, the operational base for the great oceanographic Challenger Expedition of 1872–6. One of its naval crew was J.H. Balfour’s son Andrew, Cleghorn’s godson, who had been christened in 1851 in Cousin’s St Thomas’s. In recent years Wardie Lodge has been brutally extended, if for the worthiest of aims, as St Columba’s Hospice.

Lying immediately to the west of Wardie Lodge and of more modest proportions, if still substantial, are what are now three cottages (West, East and South) originally associated with the much older Wardie House. The mansion itself had Renaissance origins, but seems to have been poorly documented before its demolition in 1955. It is said to have been extensively repaired in the late eighteenth century by a ‘Sir Alexander Boswell’; the spelling of the surname varies, but came to be standardised as ‘Boswall’. The man has also been referred to as ‘Dr Alexander Boswell’, but in fact was a plain ‘Esquire’, whose main mansion was Blackadder in Berwickshire. The most authoritative source on him, rather surprisingly, is the Soane Museum, as this ‘rich bachelor’ asked Robert Adam to rebuild Blackadder, work that seems to have been carried out, at least in part (it too has been demolished). Until his death in 1848 (a date found with difficulty, but given in his fellowship record of the Royal Society of Edinburgh) the early nineteenth-century owner of Wardie House was John Donaldson Boswall, a Captain in the Royal Navy, who had hoped to develop the coal deposits on the estate.

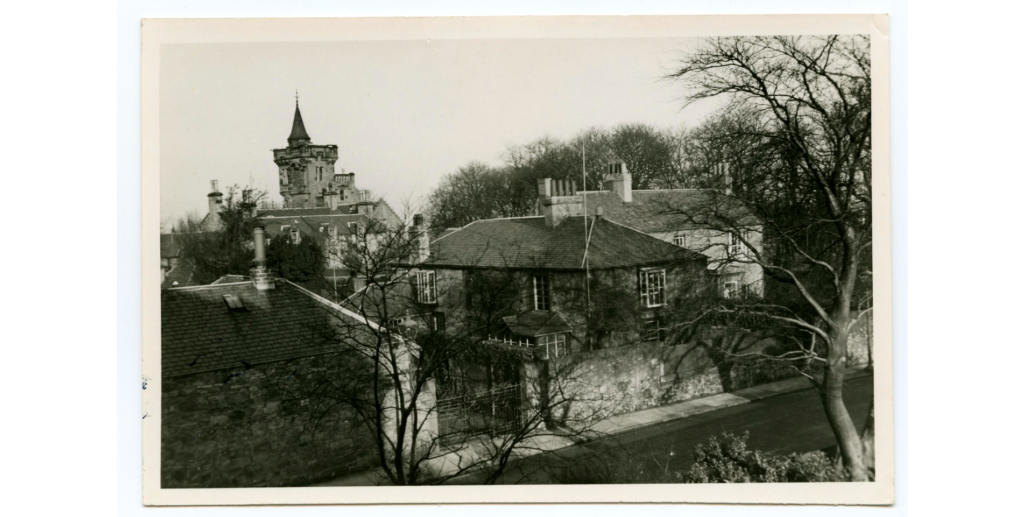

There is much confusing information about the Boswalls on the net, but from a seemingly authoritative source on naval history it appears that Captain Boswall was born John Donaldson in Fife in 1790 and changed his name in 1812, having been designated heir to his relation (of unknown degree) Alexander Boswell. Alexander must later have changed his mind (rich bachelors!), so that while John inherited Wardie, he failed to get the much grander Blackadder. After the Captain’s death the house was sold, or perhaps let for a few years, to Michael Anderson a Hanover Street based law printer. Boswall had a son and a daughter: John Roper Donaldson (1826–1883) joined the Madras Army and ended up a Major General; Alexandrina Janet (b 1823) married the Rev Philip Kelland, Edinburgh professor of mathematics and, despite living not far away at 6 Inverleith Row, the couple kept the first of the cottages under consideration here. West Cottage was attached to the western end of the big house and survives. In about 1859 the mansion was bought by Thomas B. Yule, a Leith merchant, who employed James Campbell Walker to enlarge it – not least with a baronial tower that can be seen rearing above South Cottage, in the photograph taken to show the death place of Edward Forbes for the Manx Museum in 1954, the year before the mansion was torn down.

And so, at last, we come to South Cottage. Today this is No. 9 Boswall Road and refers to a low, but two-storeyed building set end-on to the road. Its first-floor windows have lying panes; from the one on the south gable onto the street, and another on its western wall, project intriguing, glazed boxes, which must have been miniature conservatories. At right angles to this is No. 11, now East Cottage, a taller, three-bayed, two-storeyed house. All the town plans and Ordnance Survey maps, from 1817 onwards, show a single building, of much the same ground plan, the whole ensemble called South Cottage, so East Cottage is the result of a relatively recent subdivision. The group could well have been an eighteenth-century farm associated with Wardie House.

Local-history websites claim that ‘East Cottage’ was the summer residence of the author and critic ‘Christopher North’, whose real name was John Wilson (1785–1854), Edinburgh professor of Moral Philosophy from 1820 to 1854. This led me to imagine a commune of academics seeking refuge from the pollution of Auld Reekie beside the sea air of the Firth. Although in 1864 George James Allman, Forbes’s successor as professor of Natural History, did (from a letter to Balfour) live in West Cottage, there is no evidence for Wilson’s presence in the vicinity. East Cottage didn’t even exist in his time and while in Edinburgh he lived at 6 Gloucester Place and summered at Elleray, his estate near Windermere. If he did ever rent South Cottage it must have been for a very short time.

As for the owners of South Cottage, it first appears in the Post Office directories in 1848/9 (prior to this possibly taken as an appendage to Wardie House), when it belonged to John Howkins, a civil engineer, who the following year moved to Queensberry Place, the picturesque villa of 1855 – multi-gabled and chimney-stacked – now No. 174 Granton Road, which McPevsner hints might be by David Bryce. From this year until 1862/3 – that is during the time when it was briefly rented by Edward Forbes – the house belonged to a Miss Howkins, presumably a sister or aunt of John. The reason for Forbes’s renting the cottage in 1854 during his tragically short tenure of the chair of Natural History, and before he could be joined by his wife and family from London, turns out not to have been for its sea air or marine zoology, but to be close to his friend Captain Henry James of the Royal Engineers, who lived in the fine villa opposite Queensberry Place called Erneston.

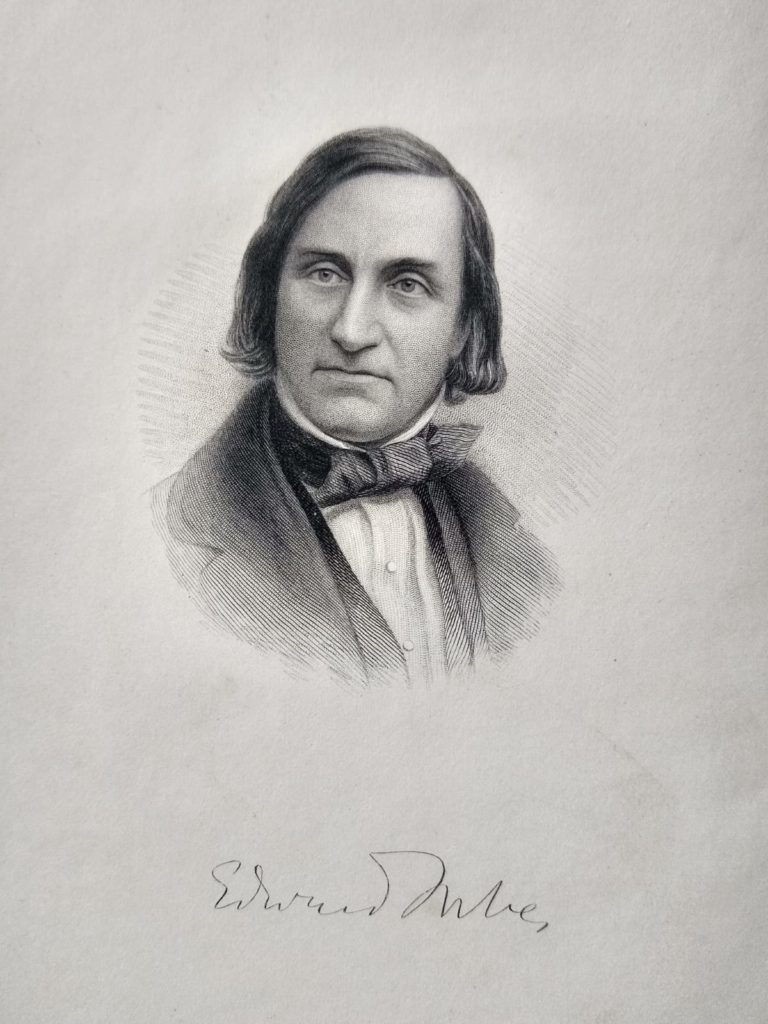

John Goodsir

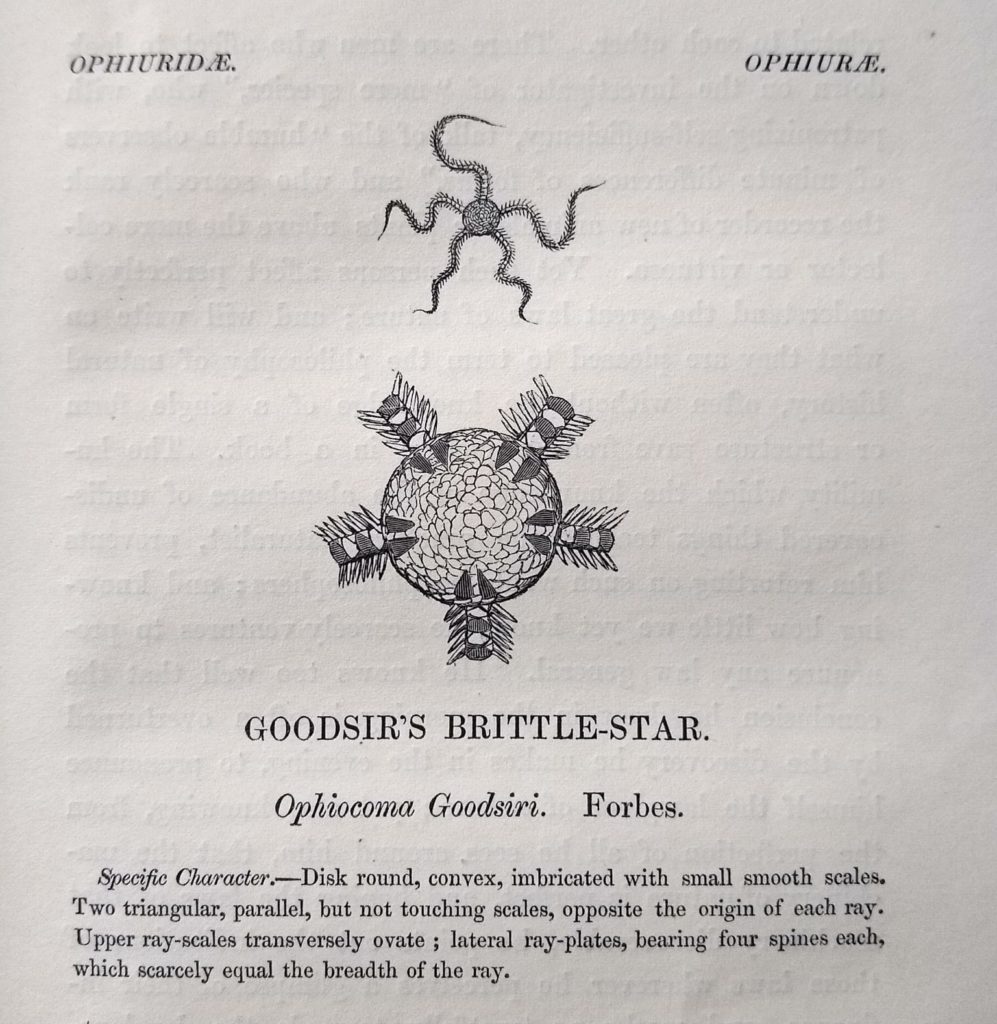

Goodsir was born in Anstruther in 1814 where, as noted earlier, his father was the town’s surgeon. In 1830 the younger John was apprenticed to a dentist in Edinburgh, where he took more interest in anatomy and attended the lectures of Robert Knox. Through this he became friendly with the charismatic Edward Forbes and a member of his ‘Universal Brotherhood of the Friends of Truth’, a group whose badge was a triangle inscribed with the Greek words eros, oinos, mathesis (love, wine, learning). Although Goodsir returned to Anstruther to assist his father between 1835 and 1840, he made an expedition with Forbes to study marine invertebrates in Orkney and Shetland in 1839, from which Forbes named a brittle-star for his friend.

In 1841 Goodsir returned to Edinburgh and lived in the flat at 21 Lothian Street with Forbes and with his brothers Harry and Robert. Goodsir started to lecture on anatomy and became assistant to Alexander Monro Tertius whom he succeeded in the chair of anatomy in 1846, at the age of only 32. Having absorbed Knox’s Continental ideas on transcendental anatomy (the seeking for archetypal forms and unifying principles in the organisation of organic life) Goodsir sought this in studies of comparative anatomy and embryology. His skill in microscopy, and the use of improved, achromatic instruments, allowed him to recognise the cell as the fundamental unit of higher organisms and, in unicellular organisms such as red snow (Protococcus [now Chlamydomonas] nivalis, correctly identified by Agardh and Greville as algal), the common link between the animal and vegetable kingdoms. Through the 1840s and ’50s Goodsir developed his ideas on the fundamental importance of what is now known as the eukaryotic cell: the role of the nucleus in its propagation and the membrane as the basic unit of absorption and secretion. ‘The nucleated cell is potentially … an organism’. This was Goodsir’s major contribution to biology, later and more famously, developed by Rudolf Virchow. Goodsir’s teaching, not least of microscopy, was influential and has been seen as part of the phenomenon ‘whereby British medical schools created a seedbed for Victorian life science’.

The major forum and co-ordinating body for mid-nineteenth-century science (despite its lampooning by Dickens as the Mudfog Society for the Advancement of Everything) was the British Association for the Advancement of Science. The BAAS paid generously for the dredging work undertaken by Forbes to be discussed below, and at its 1850 Edinburgh meeting it was Goodsir who chaired ‘Section D’, devoted to natural history. This was the section to which Cleghorn read his first papers, and that commissioned the ground-breaking report on tropical deforestation of which, a year later at Ipswich, Cleghorn would prove to have been the major author.

Edward Forbes

Forbes was born on 12 February 1815 on the Isle of Man, son of a prosperous banker. The name (as in the similar Scottish names Purves and Innes) was pronounced with two syllables: Edward used a logo of four bees and signed many of his cartoons ‘BBBB’. His short life was action-packed and varied, starting with a brief period of artistic training in London; his exquisite drawings and caricatures adorn many of his scientific works. In 1831, at the age of 16, he was sent to Edinburgh to study medicine. His loveable and ebullient personality struck all who encountered him, not least John Goodsir and their ‘oeneromathic’ brotherhood. One of the most interesting products of this period is the irreverent student magazine The University Maga, dedicated to ‘Christopher North’, to which Forbes contributed cartoons of professors (including Jameson, Monro and ‘North’) and of the town-gown ‘snowball riot’ of 1838.

During the five years that Forbes officially attended the university he was deeply affected by the natural history lectures of Robert Jameson and especially, like Goodsir, by those on anatomy by Robert Knox, infused as they were with Continental transcendental ideas. Forbes became far more interested in natural history, gave up medicine, and embarked on the then precarious career of a professional naturalist. Between 1836 and 1842 he travelled widely – from Norway to the Mediterranean – studying botany, palaeontology and especially, by means of dredging, marine invertebrates. During the Christmas vacation of 1839 he gave a series of twelve lectures on comparative zoology in St Andrews that were attended by the young Hugh Cleghorn. While walking with Goodsir on the West Sands Forbes found two species of comb jelly, which he studied using the microscopes of Sir David Brewster and Major Hugh Playfair. In 1841 Forbes published his beautifully illustrated History of British Starfishes and Other Animals of the Class Echinodermata.

From his extensive and meticulous observations Forbes developed his concept of ‘homoiozoic zones’: that groups of similar marine organisms were distributed in bands correlated with depth and latitude. He realised that present-day distributions and ecology could be used to interpret the fossil record and also wrote on the effect of glaciation in explaining distribution types within the British flora. Forbes was a High Church Tory and a creationist. Observing great diversity and structural complexity in Palaeozoic fossils he could not believe in unidirectional or progressive transmutation; he believed in repeated acts of Divine creation of generic types that were suited to the physical conditions of the time. He also believed that the concept of time itself was a human construct, by which the feeble human mind attempted to understand the unknowable breadth of creation past and present. Not interested so much in processes, his aim was to explain observable patterns in time and space and his transcendental ideas led him to apply speculative concepts such as former land bridges and, above all, that of ‘polarity’ (then much discussed in chemistry) to such phenomena. The concept is as hard to understand today as it was to his contemporaries (Darwin compared it with table turning) but Forbes thought in terms of ideal spheres of creation, with forces acting in opposite directions that resulted, for example, in the split between plants and animals.

As a result of his father’s bankruptcy in 1842 Forbes had to return to London and find paid employment. He succeeded David Don as Professor of Botany at King’s College. He then developed what would now be known as a portfolio career, juggling his botanical chair with posts as curator of the Geological Society followed by that of palaeontologist to the Geological Survey, which involved extensive fieldwork, and finally as lecturer in natural history to the Government School of Mines. This was all greatly to the detriment of his health, which had been impaired by malaria contracted in the Mediterranean. Forbes’s great aim was always to return to Edinburgh, his spiritual and intellectual home, which he could only do on the death of Robert Jameson whom he succeeded in the chair of Natural History in May 1854. It came too late. His health was shattered, he continued to rush around the country, but ended up in the rented accommodation of South Cottage. There he was attended medically by his loyal friends Balfour and Goodsir, but his life ended on 18 November 1854 at the age of only 39 and he was buried in the Dean Cemetery. His work has largely been forgotten, due to the ‘winner takes all’ version of the history of science and the apotheosis of Darwin and his school, but his life and ideas are still fascinating.

South Cottage disappears from the Post Office Directories in 1863/4 but must at this point have been acquired, either leased or purchased, by Goodsir. He never married and his choosing it was perhaps an act of homage in memory of his friendship with Forbes. Goodsir’s own health gradually broke down with a painful condition of atrophy of the spine, and it was at South Cottage that he too died, on 6 March 1867. The friends were reunited in death as Goodsir’s obelisk is adjacent to that of Forbes in the Dean Cemetery. Nearby is a large stele, ornamented with palmette and anthemion, to the memory of David Cousin; but this cannot mark his grave as, after the death of his wife, Cousin retired to Baton Rouge in Louisiana where he died in 1878.

This leaves an unresolved question – the plans referred to in the note from Goodsir to Cousin with which this investigation began. The site is too confined for a new building ever to have been possible, and the ground plan of the present building seems to have changed little from the earliest maps, so the project must surely refer to an alteration. Though hard to be certain, from rendering, whitewashing and the enlargement of some of its windows, the main part of the cottage has the appearance of an eighteenth-century farmhouse, of which the south limb of rubble-built whinstone could originally have been something like a stable or cart-shed. Might it have been this wing that was remodelled by Cousin – and might the later windows, with lying panes and the two ‘oriel-conservatories’, be his, perhaps for the benefit of Goodsir’s sister Jane who apparently had botanical interests?

Post Script

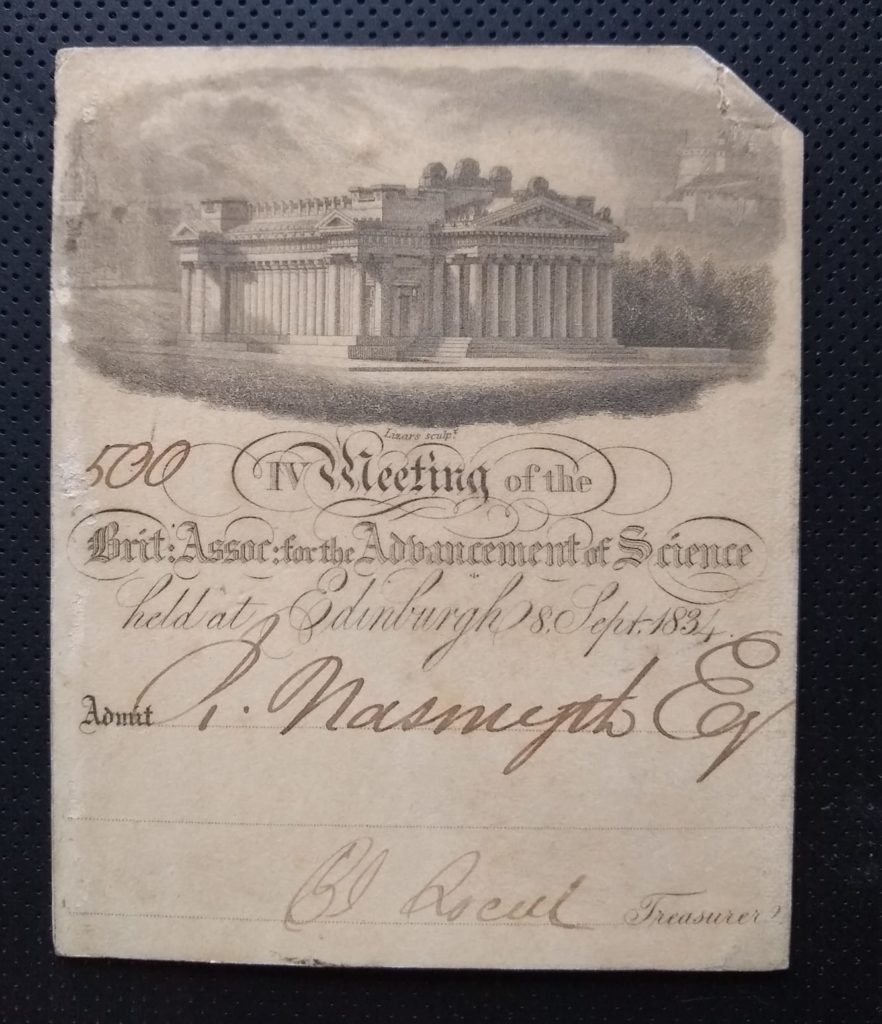

Shortly after writing this I purchased for my ephemera collection a handsome admission ticket engraved by Lizars with an illustration of the newly remodelled Royal Institution (now the Royal Scottish Academy). It is for the fourth annual meeting of the British Association held in Edinburgh under the chairmanship of the geologist Adam Sedgwick in 1834 and made out to ‘R. Nasmyth Esq.’ He turns out to be the dentist to whom John Goodsir was apprenticed at the very time of the meeting. In the 1830s Nasmyth was ‘surgeon dentist to the King’ [William IV] and lived at 78 George Street (he must have done well; as dentist to Queen Victoria he later moved to the far grander 5 Charlotte Square). But there is a slightly macabre rider to the tale. In 1869 a grave was found in arctic Canada containing a skeleton that was at the time believed to be of one of Franklin’s senior officers, in part because of the gold fillings in some of its teeth. The skeleton was repatriated and buried at Greenwich, but recent DNA analysis has shown it to belong to someone brought up in eastern Scotland. Robert Nasmyth was known for his use of gold fillings, so the skeleton is highly likely to be that of Cleghorn’s friend Harry Goodsir.