By Carole Papion

My journey around Edinburgh Botanic Gardens started about four years ago, where in 2018 I enrolled in a practice-based PhD at the Edinburgh College of Art, to begin a long-running creative enquiry into the relationships between humans and the biological group of Fungi — mainly through the lens of food.

At first, I needed mycological training and joined a mycology course at the Botanics, within a cohort of MSc students. There I met Dr Becky Yahr who welcomed me to the class and asked a simple question: ‘What are you looking for in mycology?’ My PhD project was then quite uncertain. I recall mumbling an argument about my need to learn the basics of the discipline in order to address my research topic and interview specialists for my forthcoming fieldwork. Since then, I have partly answered Becky’s question: my project explores human-mycological practices, through the techniques of ethnography and illustration, to convey the everyday experience and knowledge of fungi specialists. Illustration allows both the general public and experts to learn and reflect visually in a way that they can equally relate. Looking back on Becky’s class, I could not help myself observing students in the laboratory and noticed dialogues between formal protocols and creative expression, such as when student mycologists take pleasure in sketching what they observe through microscopes.

I returned in the late winter of that semester, to express my new knowledge through a creative reinterpretation of the Botanics Lichen Safari. My workshop, Fungi All Around, gathered fifteen art students together to illustrate lichens based on morphological prompts, e.g.: “go find and draw a shrubby greenish lichen”. The point of this participatory research was to open-up attention and even learn to care for the fungi lifeforms that one can easily spot in everyday life.

The next autumn, I followed the enthusiastic cohort of MSc students to Dawyck Botanic Garden to forage for mushrooms and study the environment they grow in. I also attended the British Lichen Society annual conference in Edinburgh and on the field trip I became further enchanted with the beauty and diversity of lichens. I often felt amused in observing two distinct scientific paces: lichenologists, slowly scrutinising the surfaces of barks, gradually moving through the woods; and mycologists, so eagerly hunting mushrooms that I could barely follow their tracks. Both groups were intrigued at first by the presence of me as an outsider to these scientific communities; one question led to another and to showing me vivid and peculiar specimens, which I took photographs of and jotted notes down, as they shared and explained their specialist knowledge on the spot with a keen directness.

After a few of these encounters, my supervisors and I realised it was essential that we invite a mycologist to join the supervisory team and Dr Becky Yahr kindly accepted. This has led me to pursue a highly interdisciplinary PhD, with rootings in anthropology, design, illustration, environmental humanities and mycology.

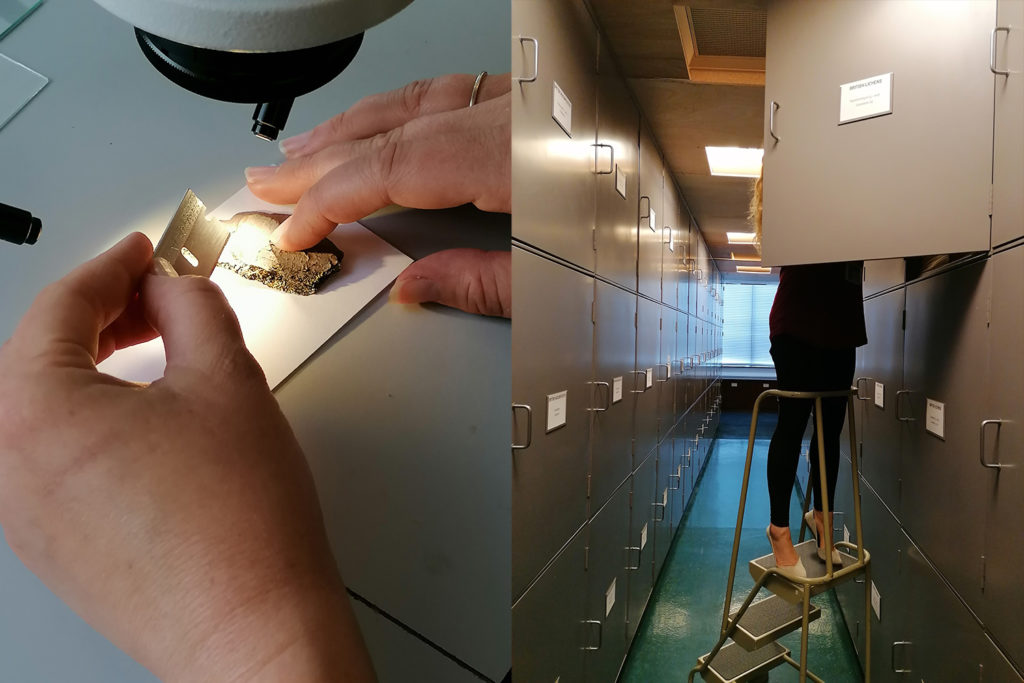

Since the pandemic, I have continued much of my fieldwork in rural France. But I have recently returned to the Botanic Gardens as an artist in residency, delving deeper into the scientific community there and the Herbarium’s fungi collection. Therefore, during summer 2022, I was based in a laboratory adjacent to the Herbarium — this used to be the Mycology department, but is now becoming renamed to cover Fungi and Bryophytes. There I observed students classifying lichens collected on a field trip and I would come and go to meetings and draw. In the third week, I produced an exhibition in the Library Foyer of the Science Buildings, displaying my illustrations produced during the residency within the academic context of my PhD studies. The foyer is a useful and interesting crossroads where staff and scientists pass by many times per day. Many would stop for a few minutes, observe some of the works and then go on their way to meetings or lunch.

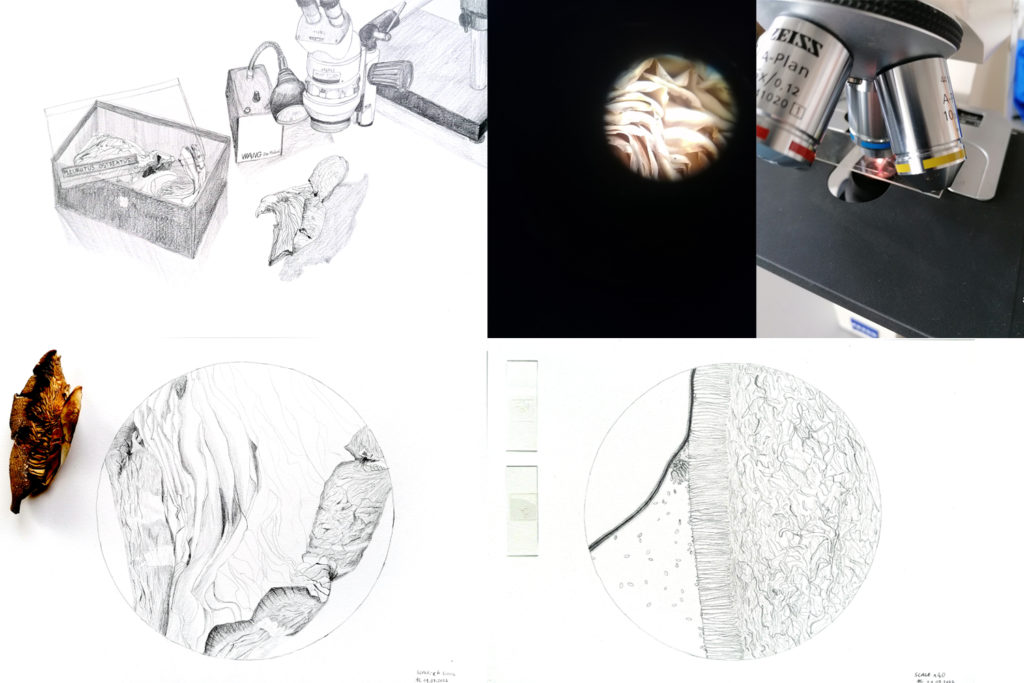

My illustrative work is not botanical illustration, as such. Rather, I work with illustration as a technique to observe, document and reflect on the everyday activities of specialists as they analyse, preserve, eat, care for or fight fungi. At the Botanics, I started through observing and communicating everyday lab practices with fungi. The series Scale illustrates Pleurotus ostreatus (an oyster mushroom) as it is observed through increasing scales and with magnification tools. I initially started drawing only with the use of my eyes, with the mushroom placed on the bench under the dissecting microscope. I would soon use the latter to observe the gills and cut a piece to prepare a slide for a more powerful microscope. This then enabled me to visually explore the spores, basidia and hyphae threads.

During an interview with the curator of fungi collections, she showed me delicate net-like lichens and other hidden gems in the Herbarium cabinets. She handled them with a lot of care, admitting her protective disposition towards fungi. These observations inspired the series Fragility. Here, I proceeded in carefully searching through folders of dried mushrooms to discover stories and narratives concerning their collection. From there, I went on to depicting the delicately folded papers and tailored wrappings which protect mushrooms from bugs, the occasional careless hands and time. Charcoal drawings revealed the cracks in their textures, their shrunken or weakened compositions, the layers of handwriting and labels, and the various discolourations of paper.

Plants’ luggages was the third and final series of illustrations I worked on during my residency. This series was informed by conversations with researchers studying micro-fungi — one of the Botanics’ established expertise, important for sustainable agriculture and forestry. Endophytes and pathogens live discreetly inside plants and travel with them through global exchanges. Such insights on plants and fungi movements drew me to reading further mycological literature and sketching two micro-fungi that are studied by the researchers I met: Oxydothis, symbiotic harmless endophytes to palm trees; and Phytothphora ramorum, a unnerving destroyer of plants and successive habitats. I composed a diptych style illustration showing the various impacts of travelling micro-fungi.

The three summer weeks at the Botanics were educationally intense and enriching, marking the conclusion of my doctoral fieldwork. I now move into the the final years of my PhD where I am to produce a thesis of writing and illustrative works. In entering this phase it feels like I am sorting through the heterogenous content of a foraging basket filled with many vivid stories and depictions of human-fungi life.

Please find the recollection of the whole journey at the Botanics on my website at: carolepapion.com.