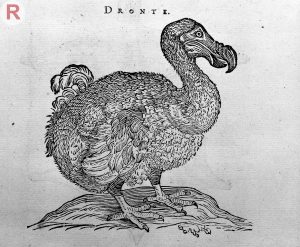

The Sapotaceae plant family provides us with some wonderful examples of the sometimes intricate interactions plants have with animals. One of the more intriguing cases is that of the so called dodo tree, or tambalacoque. Like many members of the Sapotaceae family the tambalacoque tree, known to botanists as Sideroxylon grandiflorum, is a tropical species. It is found only on the island of Mauritius, home of the now extinct flightless dodo bird.

In the 1970s there was concern that the tambalacoque tree was on the brink of extinction. There were supposedly only 13 specimens left, all estimated to be about 300 years old. The true age could not be determined because, like most tropical trees, tambalacoque has no growth rings. Scientist Stanley Temple came up with the theory that the tree relied upon the dodo to complete its life cycle. Temple thought that before the tough seeds would germinate they must first pass through the digestive system of the dodo. The idea was that the abrasion in the bird’s gizzard and the stomach acids would start to breakdown the seeds surface, allowing water to penetrate and triggering germination.

The extinction of the dodo in the 17th century, due to hunting by people, was linked by Temple to the absence of young trees. Put simply, the extinction of the dodo was preventing the tambalacoque from regenerating and the tree seemed doomed to go the same way.

This was a compelling and plausible story, and not surprisingly captured people’s attention. However, the story has a more positive postscript. Further research has shown that surviving tortoises are also likely to disperse the seeds of this tree, and more tambalacoque trees have been found, including some younger individuals. Although now discredited as the sole agent of dispersal, the dodo’s relationship with this tree still continues to fascinate.

Animal interactions with other members of the Sapotaceae family include some equally fascinating stories. A relative of the tambalacoque in the same genus, Sideroxylon inerme, the white milkwood tree, attracts a wide variety of animals to feed on its flowers and fruits. This southern African coastal tree has fruits, similar to blackberries, that are delicacies for bats, monkeys and bush pigs. While the small, greenish and rather malodorous flowers, are a favourite food of the speckled mousebird with its distinctive brown head crest.

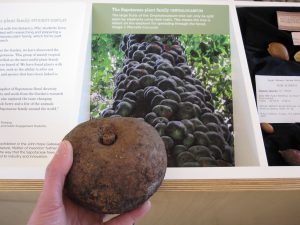

Whole fruit of Omphalocarpum from the research collection in the Herbarium. The image behind shows the trunk of a tree studded with fruit.

In Africa’s tropical forests Omphalocarpum elatum produces fruits that can be as much as two kilos in weight. These large fruits are sought after by the forest elephants, and it is only the elephants that can break through the hard shell. When the fruit falls to the ground the sound echoes through the depths of the forest and attracts elephants. They always follow a specific path, specially carved out of the forest to the Omphalocarpum tree. After positioning the fruit with their trunk, the elephants skewer it with a tusk and split it open. This interaction is ecologically important, as seeds pass through the elephant’s digestive system and germinate more easily. The close connection between Omphalocarpum trees and elephants echoes the dodo tree story. However, here the tree does seem to rely on just one animal to disperse its seeds. Declines in forest elephant populations really could put pressure on Omphalocarpum trees, and this is a good example of the often unexpected interconnections in nature. This particular interaction has only recently been discovered and a short video clip of elephants feeding on Omphalocarpum fruit can be seen here.

Travelling from Africa to India, there is another species of tree in the Sapotaceae family of high economic and ecological interest. The tree in question is Madhuca longifolia, and it is vital for the life cycle of the moth – Antheraea paphia. The larvae of this moth are silkworms and they eat the leaves of the tree before building their cocoons. It is these cocoons that are collected from the wild and processed to produce the sought after wild silk, also called tussar silk. This type of silk is commercially important in India and is appreciated for its special qualities.

As well as their stories these trees show us a fundamental aspect of nature. Interactions between animals and plants are everywhere. They are both complex and dynamic, but fragile at the same time. If we ignore these connections between plants and animals more species will face the same fate as the dodo.

This post is by guest blogger Theodora Mouschounti, an MSc student studying Science Communication and Public Engagement at The University of Edinburgh. It was researched during preparations for a major new exhibition about the Sapotaceae plant family – Nature Mother of Invention – at the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh.

Gunwant Joshi

Amazing story.

I knew the story of Dodo and calvaria major. But want to know many more such stories.

Kathi Niruprince

I can’t find the answer ??

Shylaja

Is there one that goes- when dodo became extinct, roofs of nearby houses collapsed?

Answer- dodo used to feed on woodboring insects. Now they ate on roof rafters…