Plant diversity does not have to be far-flung and exotic to be worth studying; even within Scotland, there are unanswered questions about plant distributions. Growing in our towns and cities, sharing our walls and pavements, there are bryophytes, tiny mosses and liverworts. We pass these every day, step over them, walk past them, hardly noticing that they are there. Miniature ecosystems form in the mosses that grow in the mortar between our bricks, or cling to cement surfaces of our bridges, and yet, partly because they are so commonplace, we don’t usually see them at all. And we have amazingly little understanding of exactly which species are involved, or where they have come from.

Recently, we looked at plants of the common moss Schistidium to find out exactly which species grow on artificial surfaces, like cement, walls and roofs (Hofbauer et al. 2016). Our study included plants from different geographic areas, with many plants collected in Germany and Austria, where Wolfgang Hofbauer, the lead researcher on the study, works and lives. However, a small subset of the plants were collected in the UK, and so also form part of the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh’s “Barcoding the British Bryophytes” project. Of 29 Schistidium plants collected in the UK, nine were collected on natural surfaces, like boulders and cliffs, and 17 were collected on artificial surfaces, like walls and roofs (for three accessions we don’t have a record of what kind of surface they were growing on).

These UK moss samples probably belong to eight species, Schistidium crassipilum, Schistidium pruinosum, Schistidium elegantulum, Schistidium strictum, Schistidium papillosum, Schistidium apocarpum, Schistidium trichodon and Schistidium dupretii, with three of the species, Schistidium crassipilum, Schistidium elegantulum and Schistidium apocarpum, having been collected from both natural and man-made surfaces.

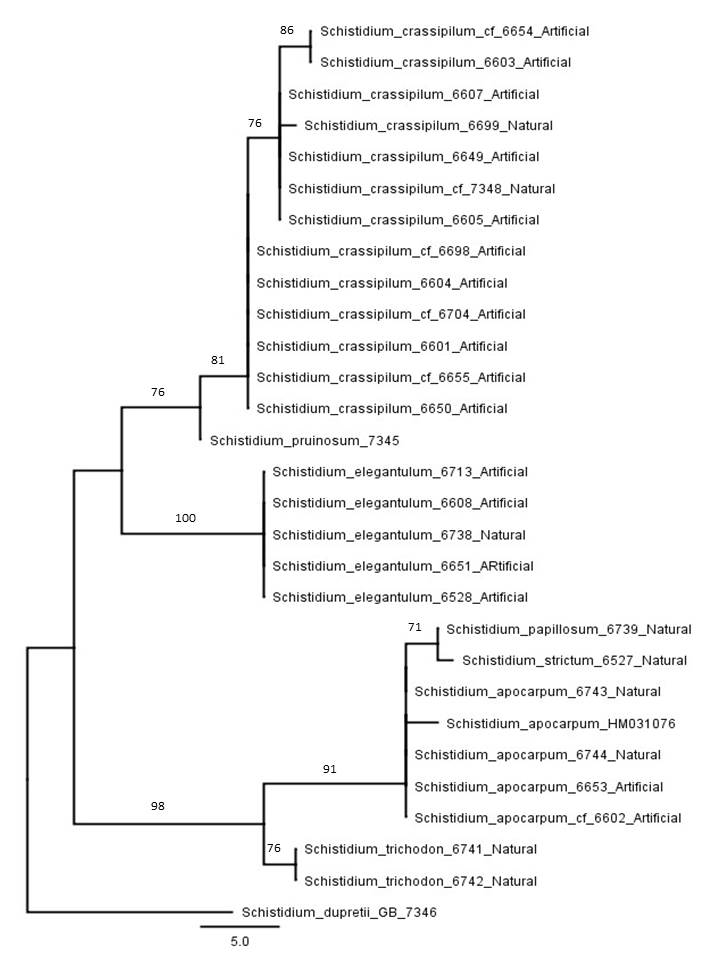

A diagram of genetic relationships between the plants we sampled is shown below.

Schistidium crassipilum – we found three distinct genetic types within this species, which may belong to different species or subspecies. Schistidium crassipilum is known to be common on man-made habitats across Britain and Ireland, and we have collected it on bricks, cement, and even roofs as well as on natural substrates.

Schistidium pruinosum – only one of the moss plants in the study, collected in the Pentlands near Edinburgh, belonged to this species. It’s not known from many collections in the UK, although this may just be because the plants are often overlooked or misidentified, rather than that they are rare.

Schistidium elegantulum – this has been reported from natural and man-made habitats to the south and west of Britain. However, in our study, we have found it growing in the east, on cement in East Lothian and Midlothian, as well as in some more traditionally westerly locations in Scotland.

Schistidium papillosum – only one of the moss plants in this study, collected from limestone in Craig Leek, near Braemar, probably belongs to this species.

Schistidium strictum – again, only one of the plants in our study, collected in Dumfries on rocks, probably belongs to this species.

Schistidium papillosum is sometimes considered to be the same species as S. strictum (e.g. by AJE Smith 1978, The Moss Flora of Britain and Ireland, Cambridge University Press, but not by Bosanquet 2010, p. 515, in Atherton, Bosanquet & Lawley, Mosses and Liverworts of Britain and Ireland a field guide, British Bryological Society), although we did find genetic differences between the two plants that we sampled, consistent with their recognition as two separate species.

Schistidium apocarpum – this is one of the more common Schistidium species, and known to occur on natural and man-made surfaces; we sampled several plants from this species, growing on walls and rocks.

Schistidium trichodon – described as “a rare upland calcicole” by Sam Bosanquet (2010, p. 515, in Atherton, Bosanquet & Lawley, Mosses and Liverworts of Britain and Ireland a field guide, British Bryological Society), both our collections matched the reported habitat, growing on limestone, in Clova and Feith, Scotland.

Schistidium dupretii – we only sampled a single British accession of this species, another rare calcicole, which had been collected at Ben Lawers.

We are still far from having full records of how much genetic diversity there is in Schistidium in the British Isles. Partly because our previous work has focused on mosses on man-made surfaces, we don’t yet have any data for several other species that have been reported from Britain and Ireland (Bosanquet 2010, in Atherton, Bosanquet & Lawley, Mosses and Liverworts of Britain and Ireland a field guide, British Bryological Society). These include Schistidium maritimum (reportedly usually northern and western, in coastal locations), Schistidium rivulare (commonly around water, particularly fast-flowing rivers), Schistidium platyphyllum (another species that grows near rivers), Schistidium agassizii (rare, aquatic and probably often overlooked), Schistidium flexipile (very infrequent, with only one record from recent years), Schistidium robustum (an uncommon upland calcicole), Schistidium confertum (an uncommon upland species), Schistidium frigidum (yet another uncommon reportedly upland species) and Schistidium atrofuscum (a rare moss, only recorded for the UK in the central Highland area).

But at least we are now starting to get a better picture of the mosses that share our towns and cities!

UK Schistidium accessions: parsimony analysis of nuclear ITS DNA sequence data, with bootstrap support above branches

Wolfgang Karl Hofbauer, Laura Lowe Forrest, Peter M. Hollingsworth, Michelle L. Hart. 2016. Preliminary insights from DNA barcoding into the diversity of mosses colonising modern building surfaces. Bryophyte Diversity and Evolution 38(1)

Sam Bosanquet. 2010. Schistidium species reports, in: Atherton, Bosanquet & Lawley, Mosses and Liverworts of Britain and Ireland a field guide, British Bryological Society.

township hack

Way trendy, some valid points! I appreciate you making this

post available, the remaining part of the website is also

high quality. Have a enjoyable.