One of the most talented Scottish surgeon-botanists ever to have worked in Asia was the Aberdonian William Jack (1795–1822), who, before succumbing to fever aged only 27, acted as physician and naturalist to Sir Stamford Raffles. Raffles had met the young prodigy through Nathaniel Wallich, while Jack was recuperating at the Calcutta Botanic Garden from an earlier illness caught in the Nepal Terai. The story of the Jack herbarium specimens now at RBGE was told in my Raffles’ Ark Redrawn: these were sent to Robert Jameson’s Edinburgh University Museum at the request of the Governor-General’s wife, the Marchioness of Hastings, in a spirit of light-hearted mockery that appears to have been somewhat unfair. In any case the joke turned sour, as these trifles are virtually the only specimens of Jack’s to have survived, his main herbarium having posthumously gone up in flames with the rest of Raffles’s collections on the Fame. In fact the Scottish Marchioness (and Countess of Loudon in her own right) had serious intellectual interests, and RBGE benefitted from numerous donations of seeds that she sent from India to Professor Robert Graham between 1817 and 1823.

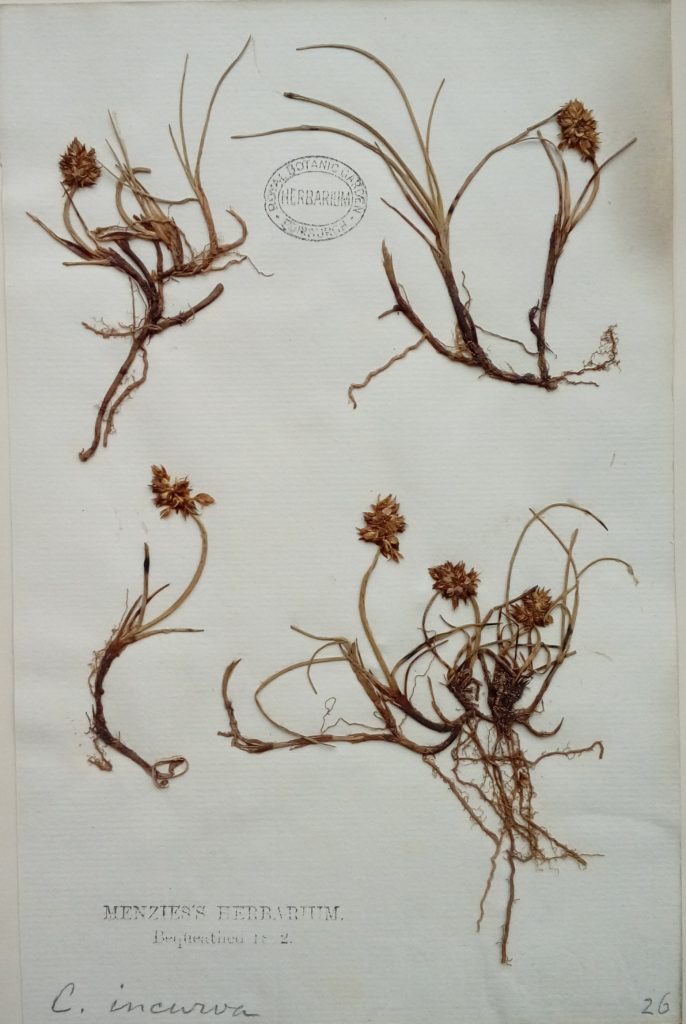

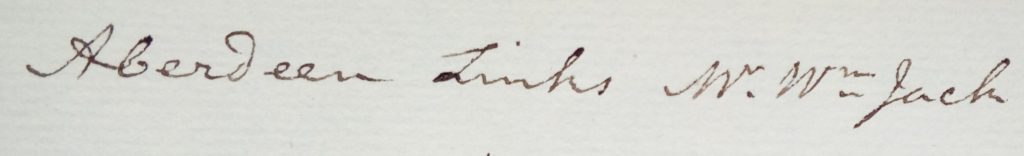

While recently laying away a specimen of Carex maritima into the British herbarium, I was extremely surprised to find one of the same species in Archibald Menzies’s herbarium labelled ‘Aberdeen Links Mr Wm. Jack’. As Menzies’s Scottish specimens were collected in the 1770s and ’80s, this was clearly not the Sumatran man. In fact, it turns out to be his father, the Rev. Dr. William Jack (1768–1854), Principal of Aberdeen University. That great biographical work on the Scottish clergy, the Fasti Ecclesiae Scoticanae, reveals that Jack senior had studied medicine at Edinburgh, and that he was the son of yet another William Jack, the Church of Scotland minister of Northmavine in Shetland. This sent me scurrying for my list of the men who attended John Hope’s lectures, and, sure enough in 1786 – the last year that Hope taught as he died in December of that year – is ‘William Jack (son to minister in Shetland)’. On the recommendation of Professor MacLeod (doubtless Hugh MacLeod, Aberdeen graduate, Professor of Ecclesiastical History at Glasgow, and a founder member of the Royal Society of Edinburgh), and as the son of a minister, Jack did not have to pay Hope’s lecture fee of 3 guineas and a class ticket of 2/6.

So, as a result of finding that specimen we have gained not only another collector for the herbarium, but the fascinating fact that the famous William Jack had botany in his upbringing and can be counted as a botanical grand-pupil of John Hope.

It is worth saying a bit more about Carex maritima, as it is a plant with which Hope had a close connection. The name that appears on the Jack sheet, Carex incurva, was first described in 1777 by the Rev John Lightfoot in the second volume of his pioneering Flora Scotica. Lightfoot stated that the plant had been ‘communicated’ to him by ‘Dr Hope, the present ingenious professor of botany in Edinburgh’, and cited specimens collected at the mouth of the Naver (in Sutherland) and near Skelberry (in southern Shetland). In fact these plants had been collected for Hope by his pupil James Robertson on (respectively) the first and third of the remarkable tours of the Highlands and Islands. These were undertaken in 1767 and 1769 for the Commissioners of the Annexed Estates. Robertson realised he had found something interesting, as in his detailed 1767 diary his field identification was ‘Carex, capitata an nova species [i.e., or an undescribed species]’. Robertson here, as elsewhere, made astute practical/ecological observations (his was a survey of potential economic resources, with a Cameralist agenda), noting that the plant grew ‘among loose sand which it seems very proper for binding, as it has creeping roots & always surmounts the sand blown over it by the wind’. It would indeed have been a new species if Robertson’s boss Hope had troubled to describe it, but by the time that Lightfoot did so a decade later under the name Carex incurva, he had been pipped to the post by the Norwegian naturalist-bishop Johann Ernst Gunnerus, who had published it in 1772, in his Flora Norvegica, with the name Carex maritima.

Maura C Flannery

Thank you for another great linking of botany and history.