Research about Victorian botanical illustrator Anne Pratt turns into a Beatrix Potter book binding mystery…

Anne Pratt was born in 1806 and, suffering from poor health as a child, spent most of her time indoors studying instead of pursuing outdoor activities with other children. Viewed as a somewhat lonely child, a friend of the family introduced Anne to botany whilst her older sister collected various flowers and plants for her, instilling a love of the subject from an early age which would carry on to the end of her life.

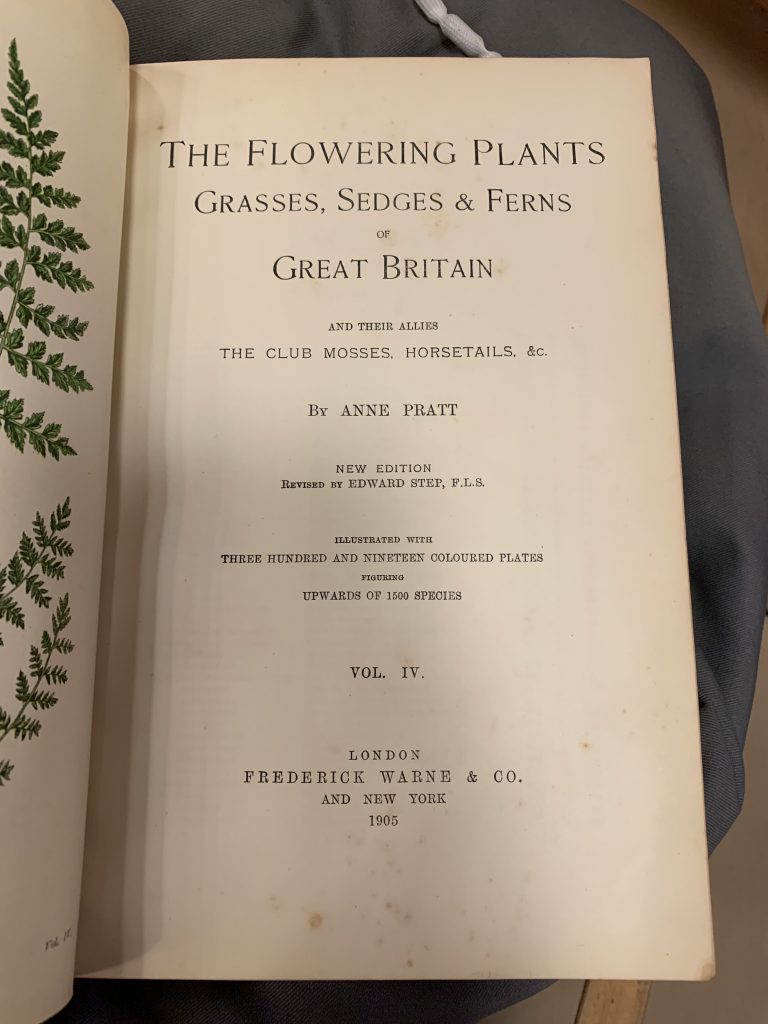

She moved to Brixton in 1826 and her first book, Flowers and their Associations, was published a couple of years later in 1828, proving to be a financial success. This led to her becoming one of the finest and most popular botanical illustrators of the time, producing around 20 books, including the five-volume Flowering Plants, Grasses, Sedges and Ferns of Great Britain (1855-66), and popularising botany through her easily accessible work and captivating illustrations.

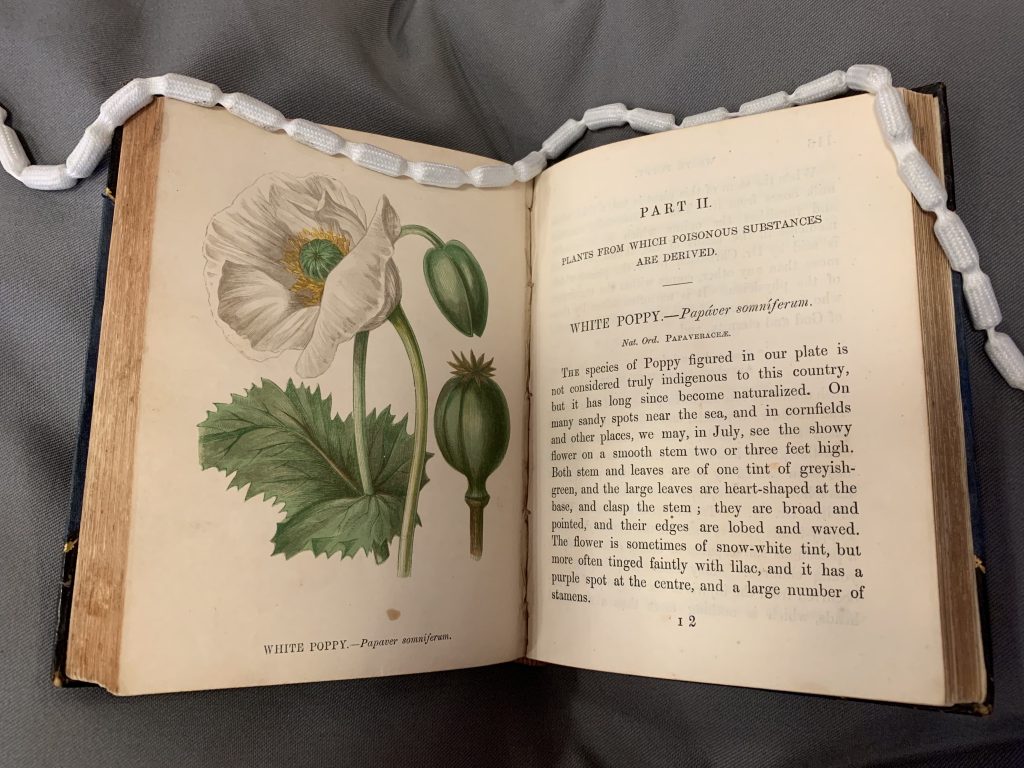

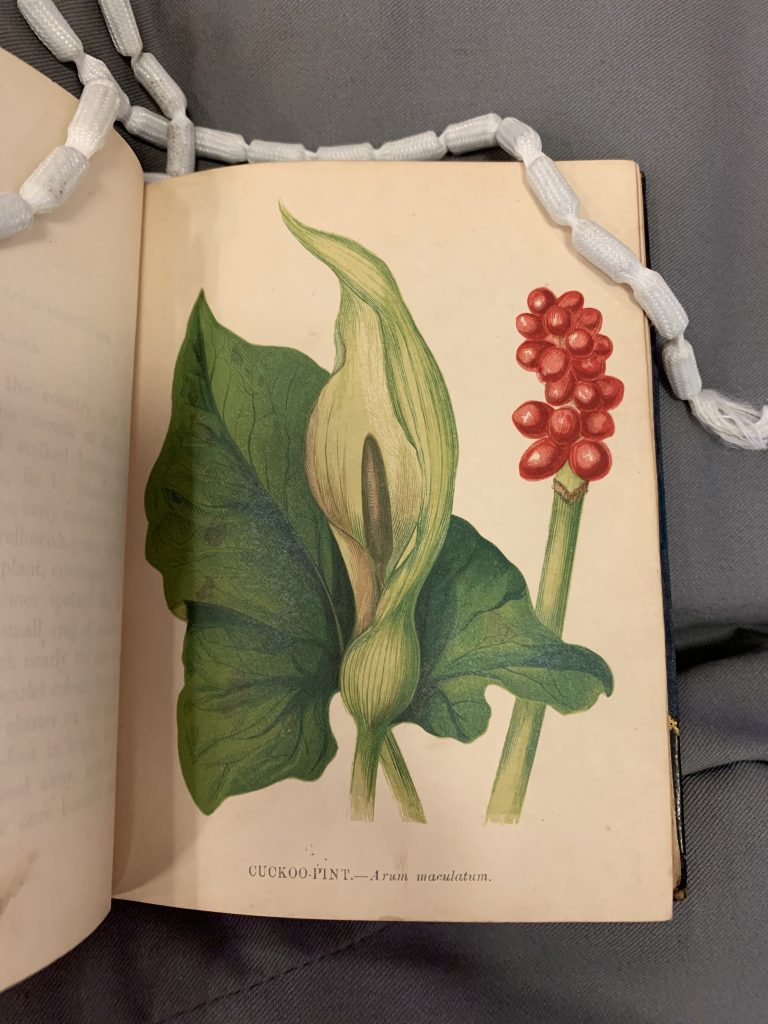

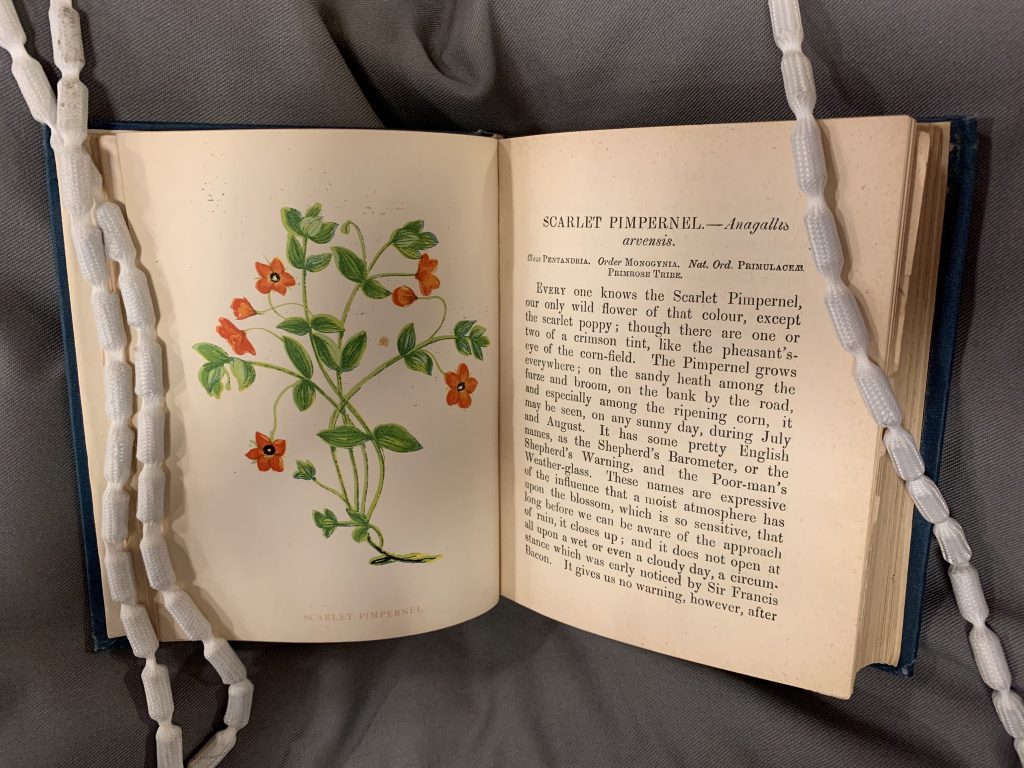

Unfortunately, as is often the case with female botanical illustrators, Anne’s work was criticized for supposedly not being scientific or accurate enough, with one critic stating that her work was ‘meager and incomplete’, whilst an art historian wrote in 1950 that ‘the drawings which illustrate her book are her own work, though in their published form no doubt owe a great deal to the artists of the firm W. Dickes and Co. who redrew them on stones’. Apparently the only basis for these remarks was that Anne was a self-taught woman and therefore not a trained ‘professional’, despite the fact that she clearly demonstrated a vast knowledge, passion, and talent for botany and illustration.

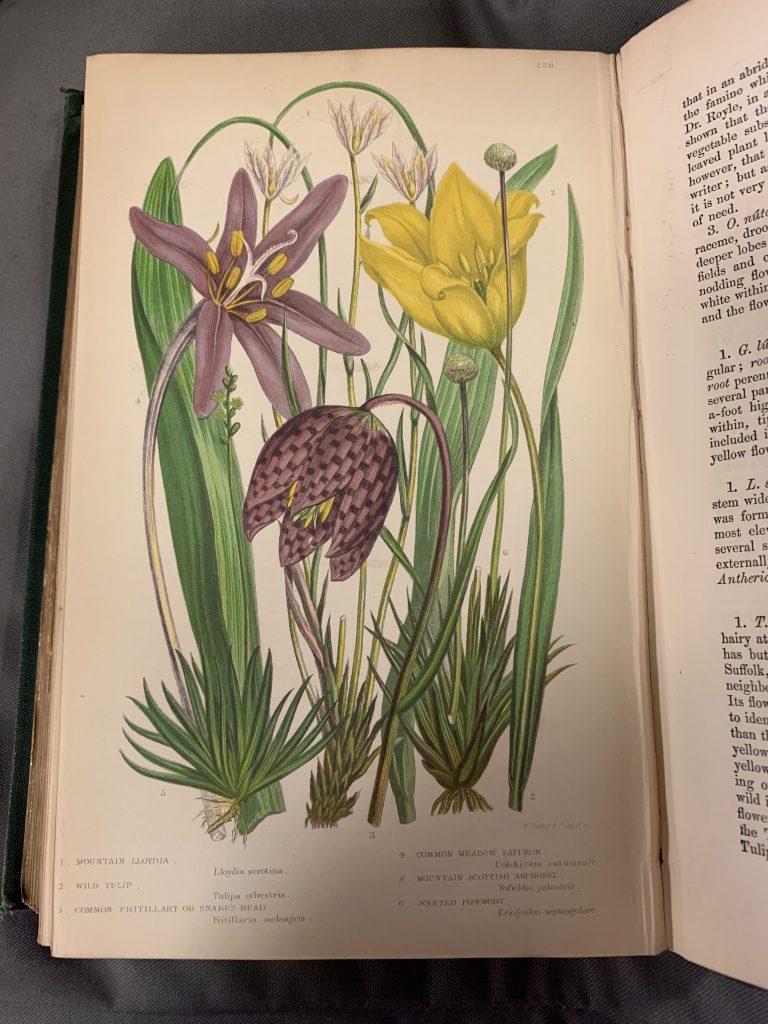

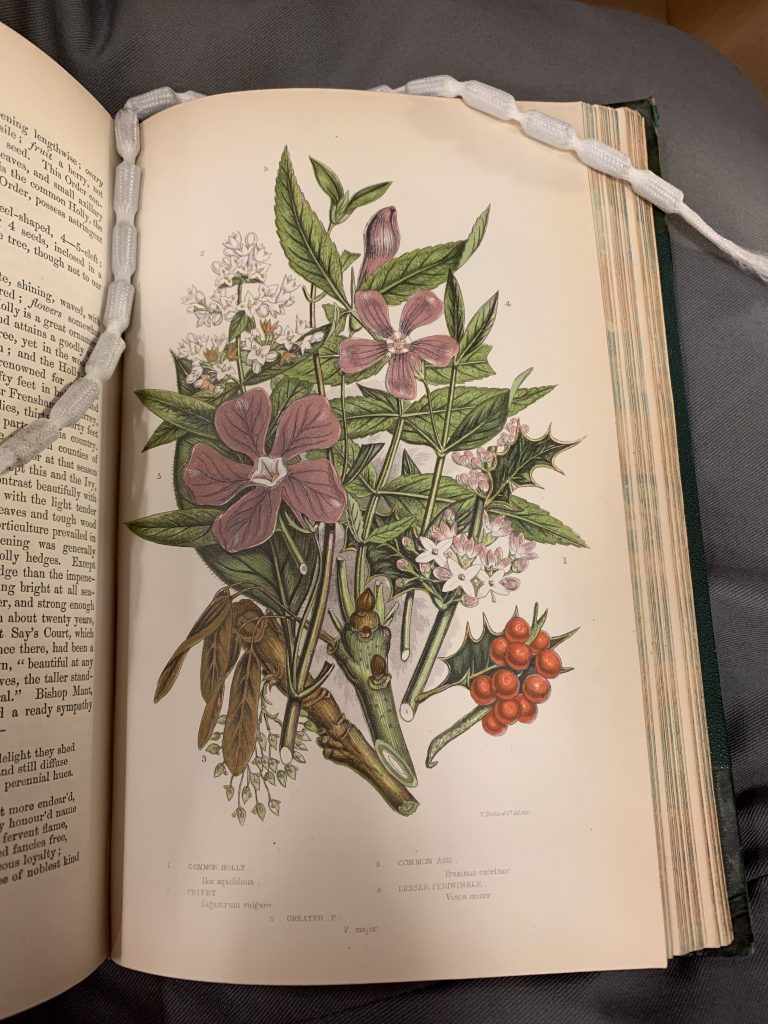

A plate from Flowering Plants of Great Britain Vol. III (1899)

Although dismissed and underappreciated by some, Anne appears to have had an overall successful and happy life, eventually settling in Shepherd’s Bush with her husband where she practiced plant therapy and wrote flower lore for contemporary women’s magazines. She passed away in 1893 at the age of 87.

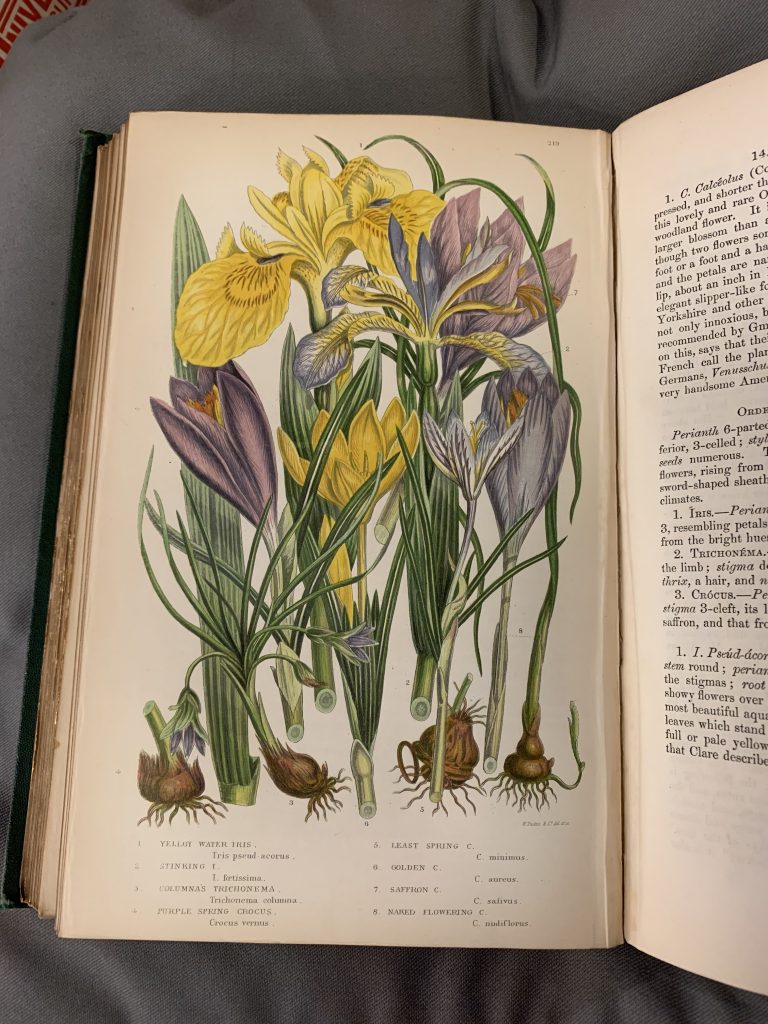

A plate from Flowering Plants of Great Britain Vol. III (1899)

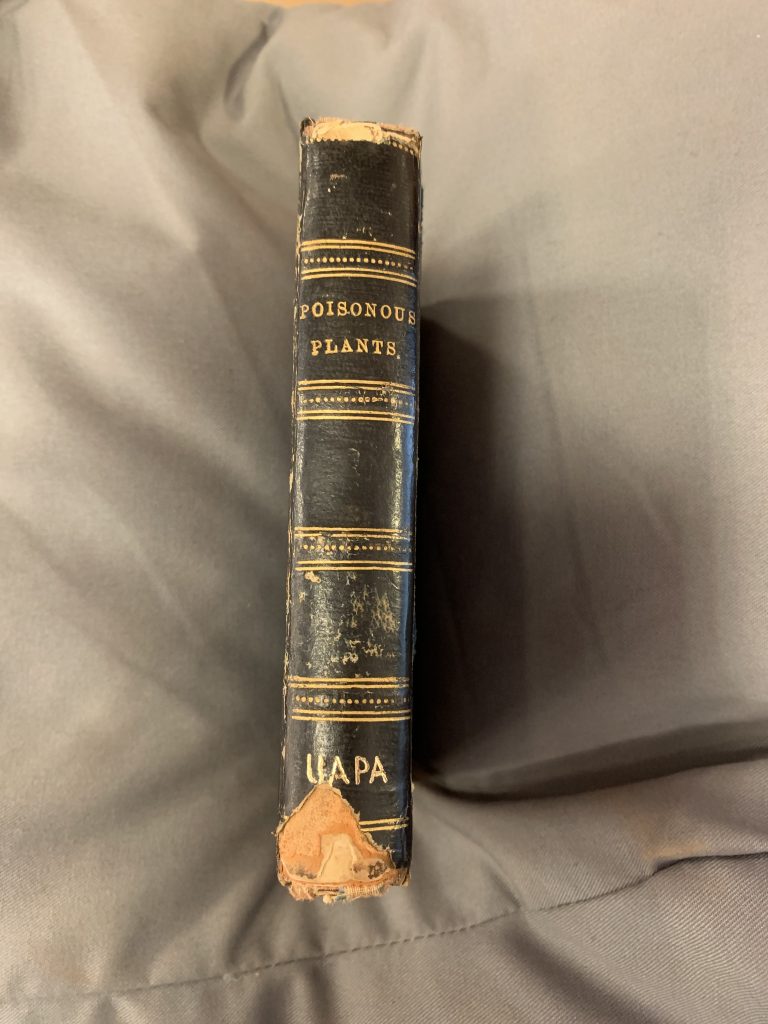

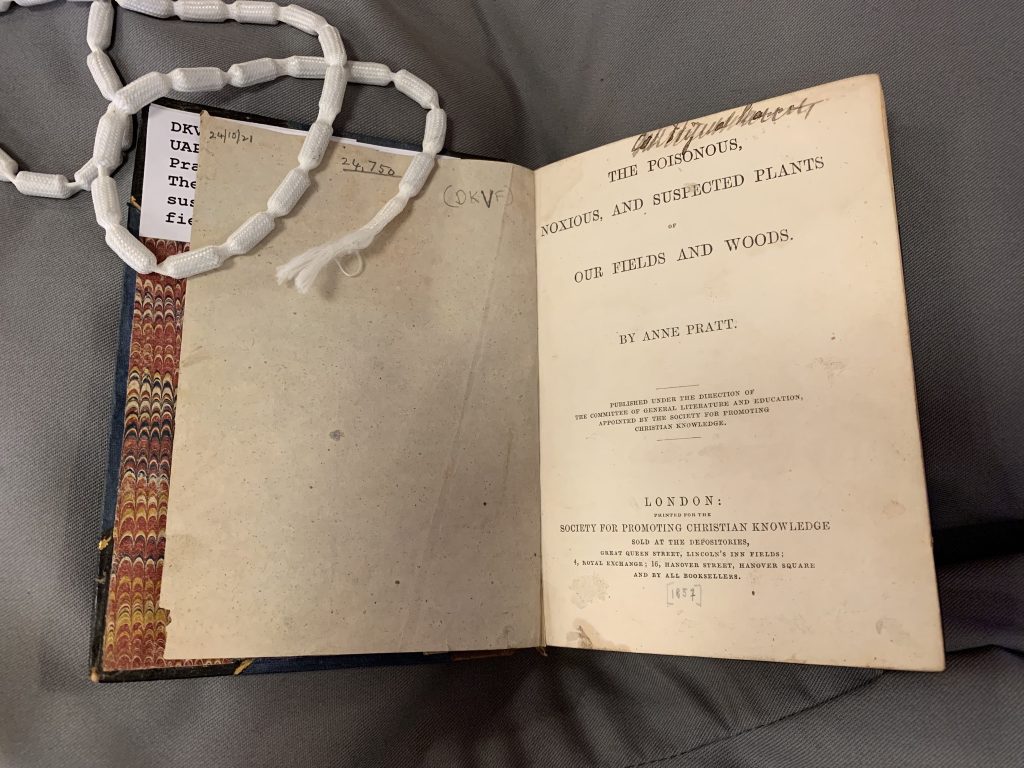

The first book of Anne’s that I encountered in RBGE’s library was The Poisonous, Noxious, and Suspected Plants of Our Fields and Woods, an intriguing book published in 1857 with POISONOUS PLANTS embossed on the spine and filled with illustrations and information about toxic plants.

Feeling disappointed that I had never heard of Anne before, I looked through the rest of her books held in the library’s collection to gather some ideas and inspiration for producing a blog post, hoping to highlight the different editions of books owned by RBGE and showcase examples of her work.

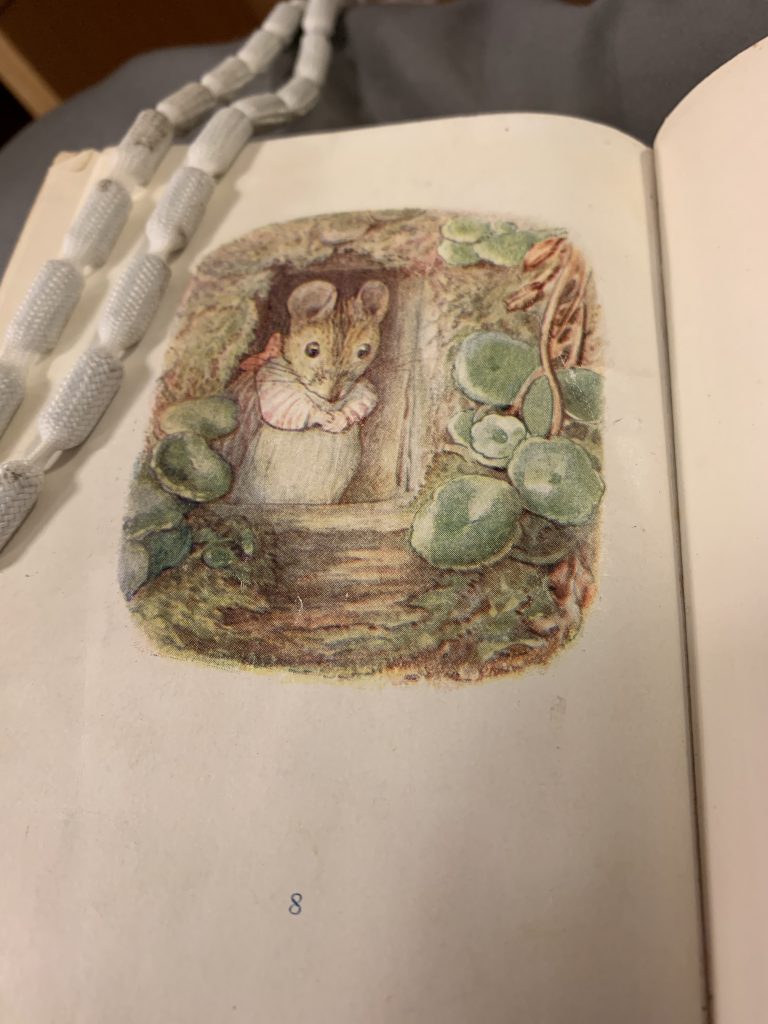

It was in one of these books that I found the recognisable image of another botanical illustrator hidden inside:

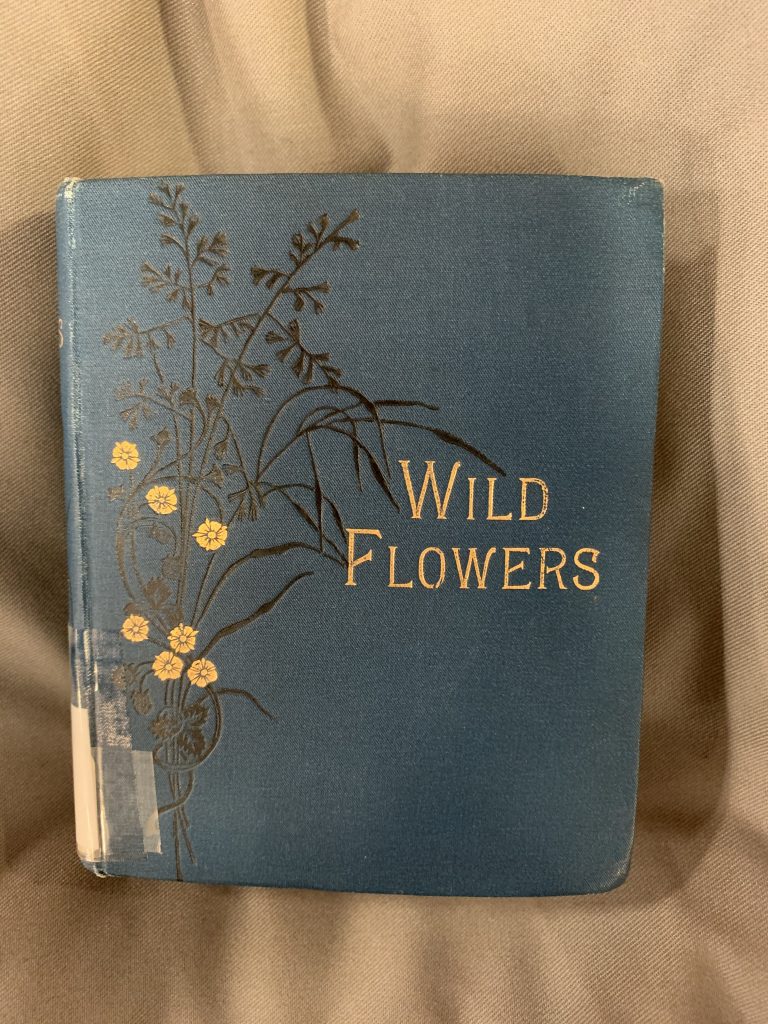

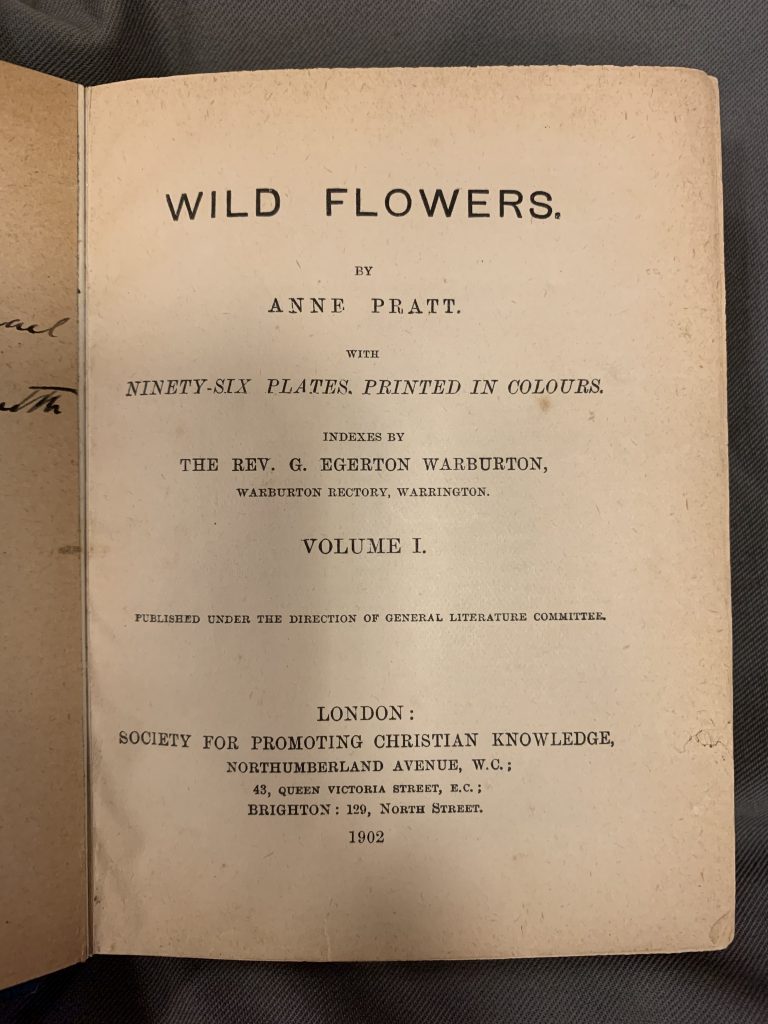

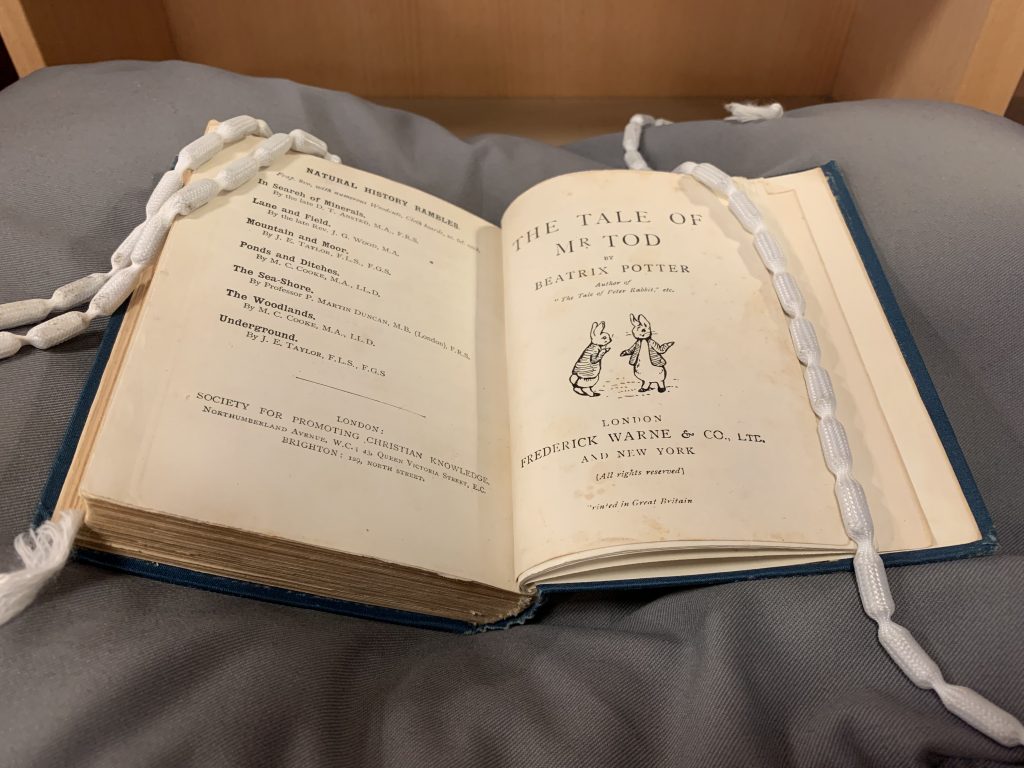

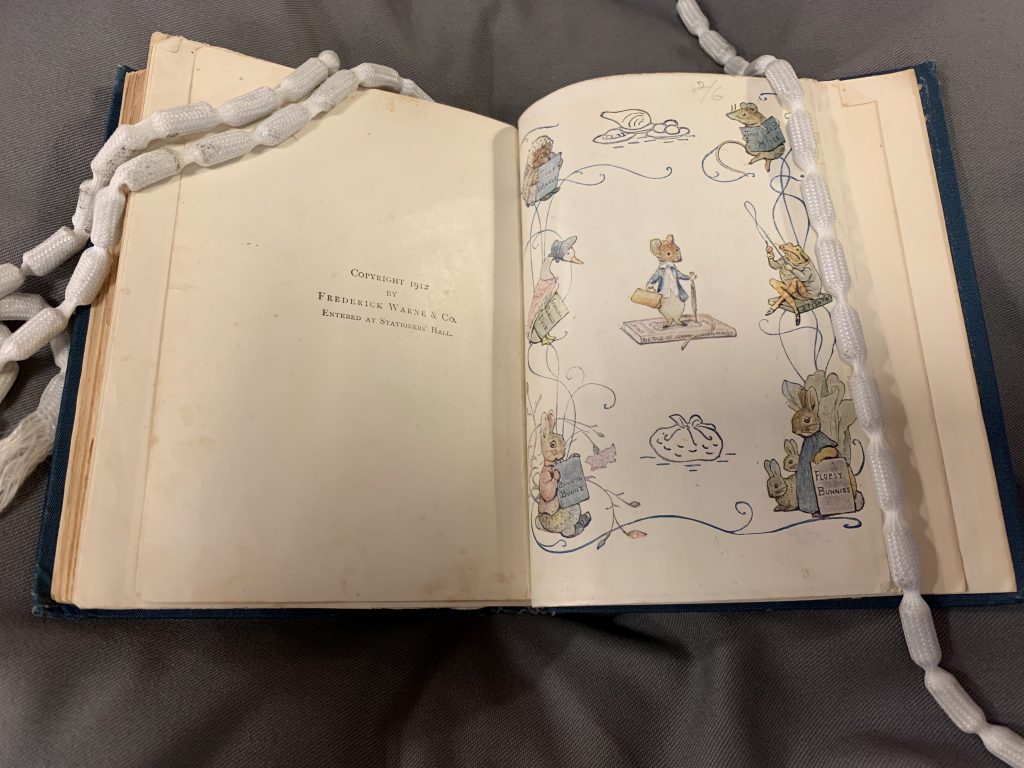

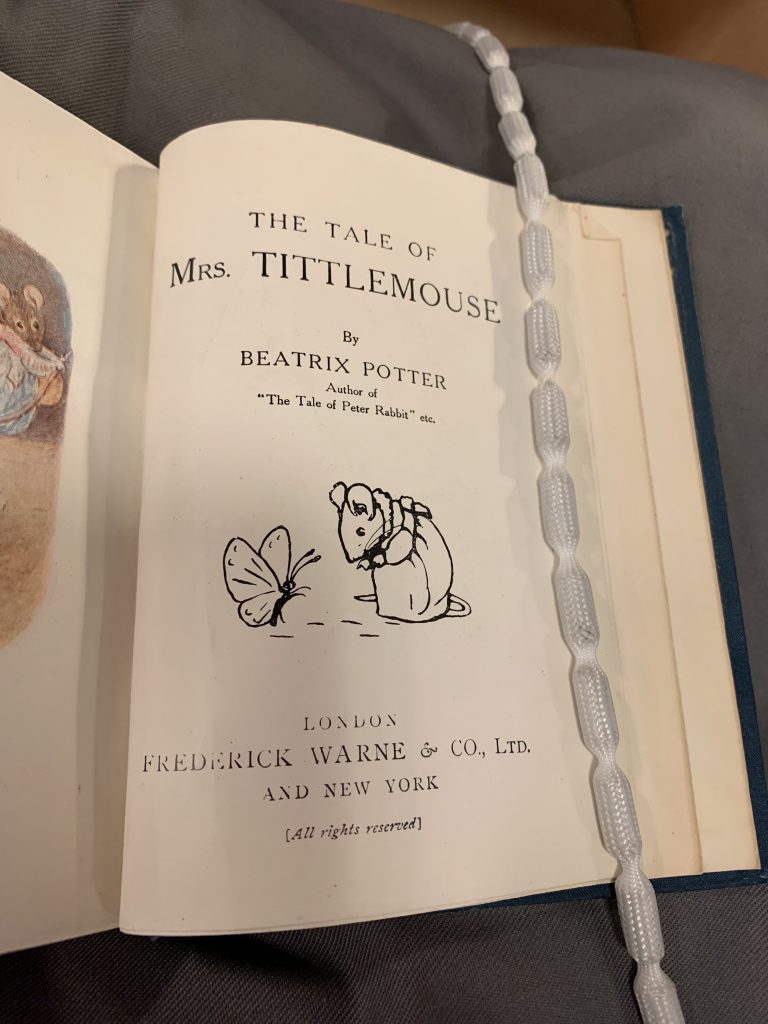

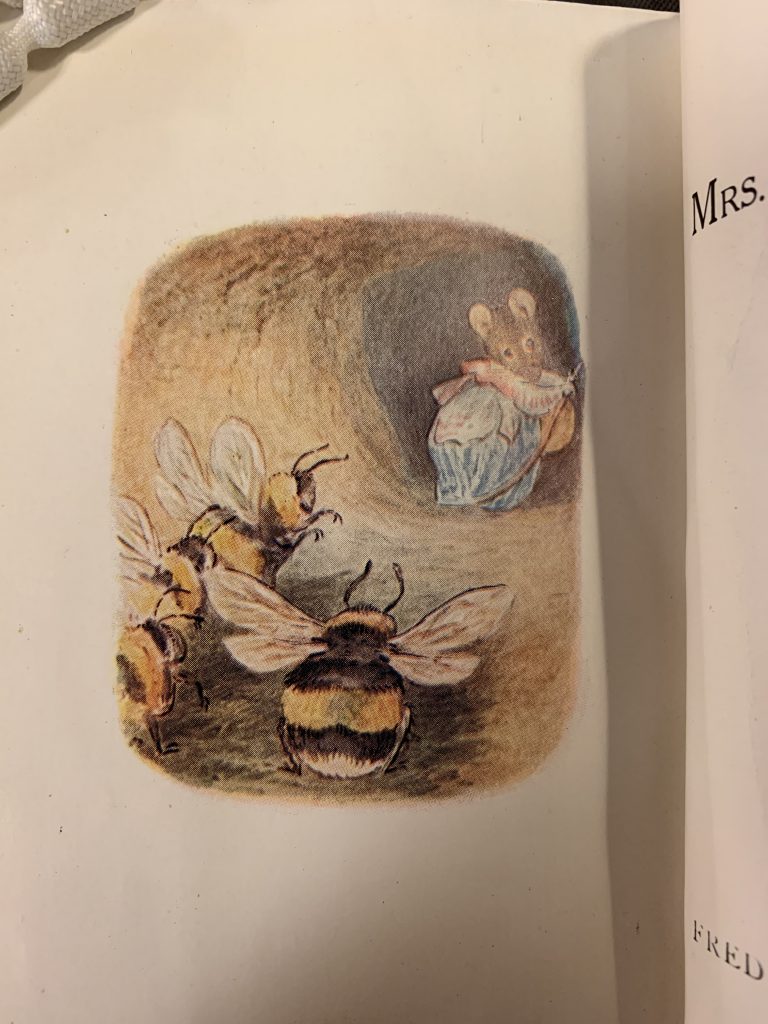

I was trying to take photos of a 1902 edition of Wild Flowers, published by the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, when the pages fell forward and I caught a glimpse of Beatrix Potter’s Mrs. Tittlemouse staring back at me. It took a few seconds for my brain to establish that this image was in the wrong book and I wasn’t just imagining things and, on closer inspection, I realised that it was bound alongside the title page for ‘The Tale of Mrs. Tittlemouse’, as well as the title page for ‘The Tale of Mr. Tod’.

One of the many joys of books is the weird and wonderful things you can find inside when you’re least expecting it, and I certainly wasn’t expecting to find Beatrix Potter title pages bound inside the back of Anne’s book on wildflowers, let alone any book on wildflowers!

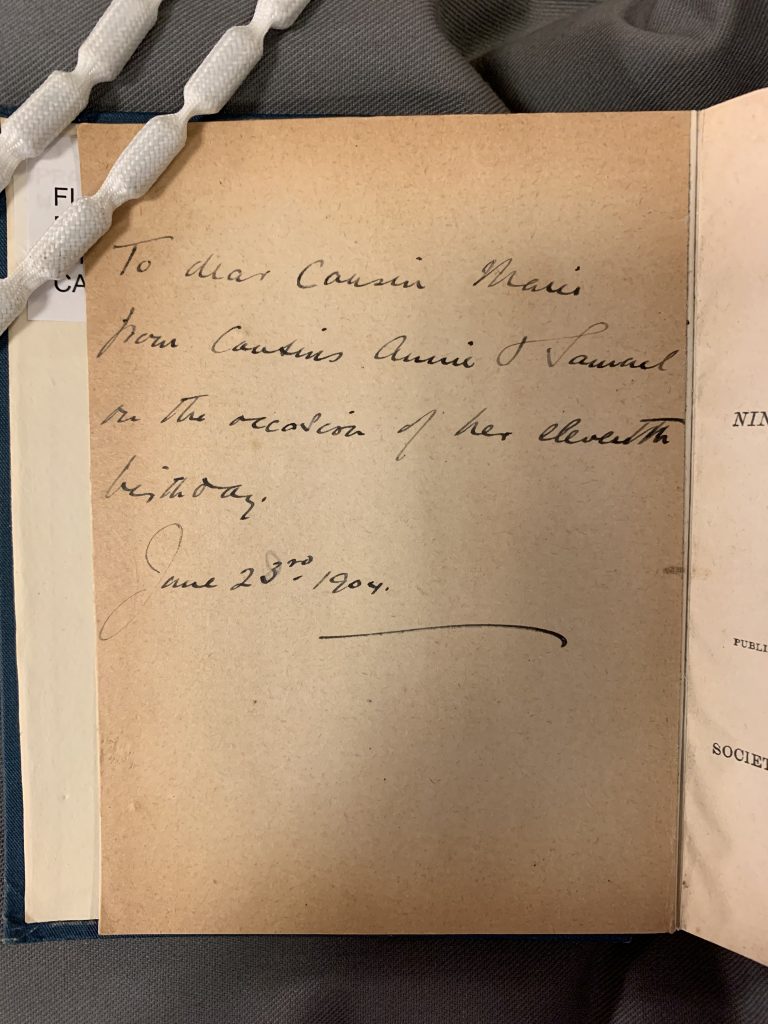

A written annotation dated June 23rd 1904 from ‘Annie & Samuel’ to their cousin on her eleventh birthday could be a potential clue, but Mrs. Tittlemouse and Mr. Tod weren’t published until 1910 and 1912 respectively, so it’s doubtful that the pages were specially bound in as an extra surprise for the child’s birthday.

There’s also the obvious connection of both Anne and Beatrix being botanical illustrators, born 60 years apart, but the clearest link I can see between the two is that Frederick Warne & Co., Beatrix Potter’s publisher, also published some of Anne Pratt’s books. I initially thought that Frederick Warne & Co. bound the images inside the book as some sort of advertisement, but this particular edition of Wild Flowers was printed by a different publisher eight years prior to the publication of Mrs. Tittlemouse.

I love a mystery, and I’d love to discover more about this unique and special book, so if anyone has an inkling, a suggestion, or can immediately solve the case, then please let me know. I’m not an expert on Beatrix Potter, nor do I know all the details about the publication history of her books, but maybe the answer is glaringly obvious to someone who has studied her. Alternatively, perhaps someone was simply practicing their bookbinding skills and happened to have the pages at hand. In any case, I think there’s something really wonderful about Anne and Beatrix, two highly successful illustrators and lovers of botany, being brought together in this way, and it would be really wonderful to find out who was behind it all.

If you would like to learn more about female botanical illustrators such as Anne Pratt, Women of Flowers: A Tribute to Victorian Women Illustrators by Jack Kramer (1996) is a good place to start and helped provide a lot of the information for this blog post.

This article was amended on 2 April 2019 to correct a sentence which wrongly suggested that the Beatrix Potter title pages were first editions.

Peggy Edwards

Hello, I am a natural science and botanical illustrator who has published articles about Robert Burns and his relationship to plants. I received an email in response to my latest article (which included photos and drawings) from a man who said, “As to your paintings of Daisy and Harebell – yes, they are artistic, thank you, but, no, neither has at all the ‘jizz’ of the wild plant!”

Reading this article and seeing that Anne Pratt received the same kind of critique, “meagre and incomplete” has brought me solace. Have times really changed? Thank-you for this article.

Karissa Adams

Hi Peggy, thank you for your comment. I’m so sorry to hear that you’ve received unhelpful feedback like that on your article, it seems very unnecessary and condescending. I’m glad my blog post about Anne brought you some solace though, as your work sounds very interesting!

Agustina

Loved this article! Please let us know if you solved the mystery.

I recently read two novels with wonderful botanist women and one of these was friends with Beatrix Potter (Seven Sisters Saga, Book nr. 3 of Lucinda Riley)

Regards from Argentina!

Karissa Adams

Thank you for the lovely words! Hopefully the mystery will be solved soon 🙂