Geography, and particularly climate, have distinguished the extreme western parts of Scotland from the rest of the country for thousands of years. Many of our rarest plant species are dependent on a delicate balance of climatic conditions that ongoing climate change threatens to unpredictably perturb.

We are used to thinking of land in terms of contemporary political and coastal boundaries, but there are other, equally valid, perspectives. If waterways and climate are seen as connecting rather than separating, then Argyle in particular (the extreme south west corner of the Scottish Highlands) might have more in common with Ireland, a mere 12 miles away across the Irish Sea, than with Central and Eastern Scotland. This was certainly the case in the early human historical period, when the kingdom of Dál Riata had strong linguistic and cultural affinities with Northern Ireland, quite distinct from the Pictish and British Kingdoms to the east (fascinatingly, there is now a view among many archaeologists that this connection stretches far back into the early Iron Age and that Gaelic, rather than arriving in Scotland via migrations from Ireland immediately after the Roman period, is, in fact, the “indigenous” language of Argyll; Campbell, 2001).

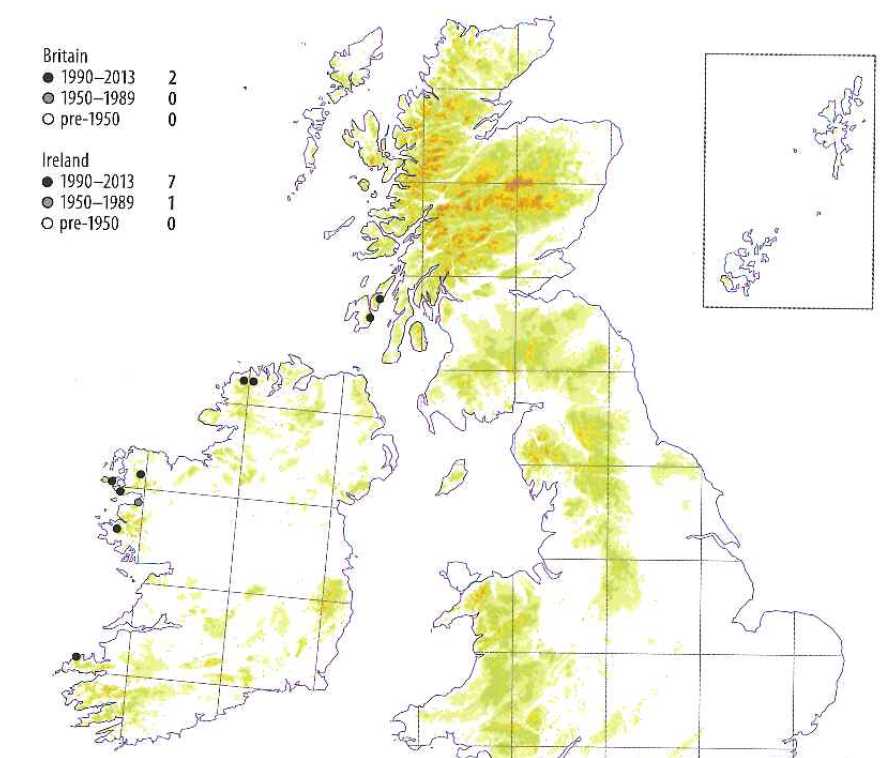

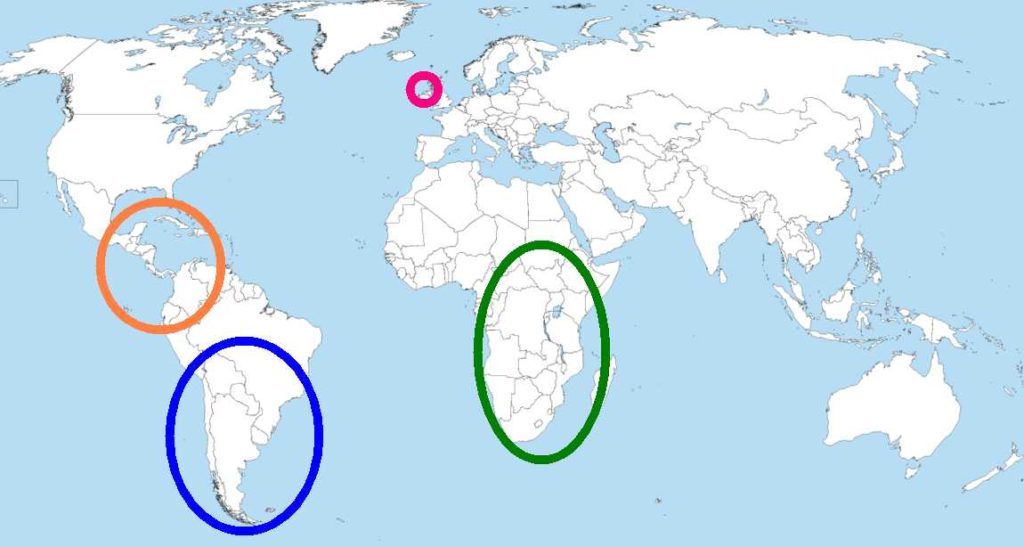

Adelanthus lindenbergianus is one of Scotland’s rarest liverworts, found only on a single hill on Islay and another (about 15km) away on Jura. Elsewhere in Europe it occurs only in Ireland, where it is also very rare and always found on hills immediately next to the Atlantic coast. The plant is a member of the suite of “oceanic-montane heath” species found on the most sheltered north- and east-facing slopes of hills in the wettest parts of the western British Isles (mostly Scotland and Ireland). Globally very rare, many members of this community are disjunct with the Himalaya (some occurring only there and in Scotland!), Western Norway and Western North America. Adelanthus lindenbergianus is an outlier in this community, however – rather than being disjunct with similar very wet environments in the northern hemisphere, outside Scotland and Ireland it is found only on mountains in sub-Saharan Africa, and in tropical and temperate Central and South America. Furthermore, it appears to be one of the most oceanic of our montane oceanic bryophytes – linked by the influence of the Atlantic to Ireland and the south west coast of Scotland, just as the Dál Riata were in human historical times.

How did this species end up in Scotland, and which of the other populations in the world are the Scottish and Irish ones most closely related to? Are all of them even members of the same species? A recent molecular phylogenetic study of the family calls this into question, showing not only that the tropical and temperate South American populations of Adelanthus lindenbergianus are genetically distinct from each other, but that each appears to be more closely related to a different species entirely (Adelanthus carabayensis and A. integerrimus respectively) than to the geographically separated populations of the same species (Feldberg et al., 2010).

A few weeks ago Maren Flagmeier and I collected material of Adelanthus lindenberganus from its Islay site in order to sequence genetic markers that should reveal its affinities. We have also obtained data from previously collected Irish material held preserved in silica gel at RBGE. The final part of the jigsaw will be provided by material from Africa (none of which has ever been sampled for molecular data) to be provided by a colleague based in Cape Town. Knowing where our unique North Atlantic representatives of Adelanthus lindenbergianus fit in the wider global picture will help us to quantify their distinctiveness and conservation value, as well as hopefully cast light on their origins. Watch this space!

References

Campbell, E. (2001). Were the Scots Irish? Antiquity 75: 285-292

Feldberg, K., J. Váňa, D.G. Long, A.J. Shaw, J. Hentschel, J. Heinrichs (2010). A phylogeny of Adelanthaceae (Jungermanniales, Marchantiophyta) based on nuclear and chloroplast DNA markers, with comments on classification, cryptic speciation and biogeography. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 55: 293-304.