The following blog was written by Chris Knowles a digitiser in the Herbarium.

Since 2021 we have increased our digitisation capacity reaching 1 million specimens imaged in August 2024. Each digitiser is assigned a family or group of plants to work through.

The RBGE collection of British Basidiomycota includes more than 3,900 species, from 446 genera in 158 families; all spread across a total of 36,778 specimens.

Before this project started only 10,737 of those had been databased, but now they are all accessible via the RBGE Herbarium catalogue.

The Basidiomycota is a division of the kingdom of fungi. For comparison, the equivalent level of division in the animal kingdom is Chordata, which includes all animals with a backbone, or spinal cord-like structures.

Basidiomycetes come in a huge diversity of shapes and sizes, from tiny rust fungi that may live only on the leaves of plants which are a couple of centimetres high to giant organisms that are measured in kilometres. But it is important to distinguish our mushrooms from our fungi, as there are luckily no mushrooms the size of a small town.

The term fungus refers to the organism itself, which is made up of long thin cells called hyphae, which together form a mycelium. This mycelium can live, eat, grow and thrive in the substrate it lives in (commonly soil or wood) without us ever being aware of it. Generally, it is only when certain environmental triggers occur that the otherwise invisible fungus may produce a structure for sexual reproduction that we can observe as a mushroom, typically with a stem, cap and gills.

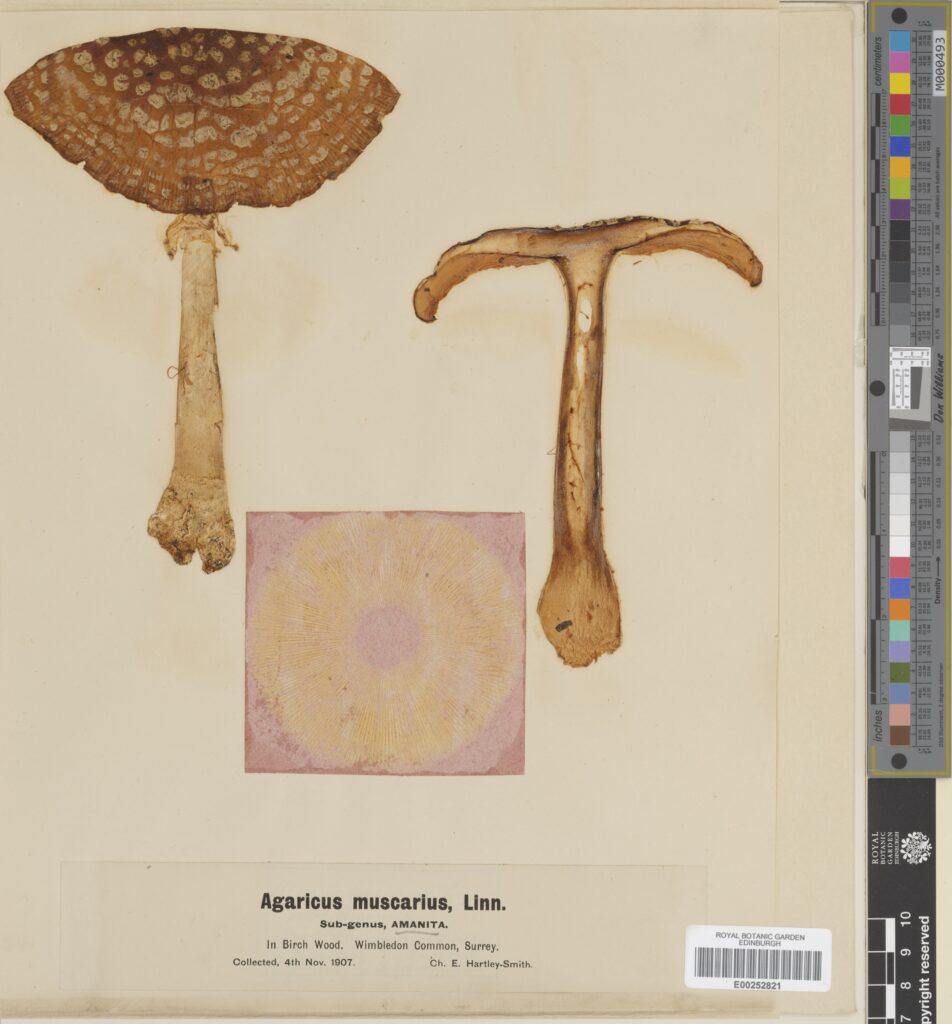

Therefore, the herbarium fungus collection consists mostly of dried specimens of these structures which are usually used to visually identify the ‘hidden’ fungal organism. Modern collections tend to include several of these mushrooms that will have been carefully dried and stored as representative samples of the species, but up until about the 1930s the collectors mounted the specimens in a way that mimicked a pressed flower specimen. Squashing a large fleshy mushroom in a flower press would of course be quite messy, so instead the specimens were thinly sliced and cut to shape to create a 2D representation of the original specimen.

A Fly Agaric, (Amanita muscaria) specimen in the field, and from a 1907 collection.

This earlier method of mounting specimens reduced the amount of material available to later researchers (for looking at under a microscope or potentially extracting DNA from). However, it was brilliant at presenting important macro-characters which could be vital for identifying a species. For example, the Fly Agaric specimen above allows us to see the markings of the cap, the internal and external structure of the stem, the way that the gills attach to the stem and even the colour of the spores they dropped.

The oldest specimens of this group in the herbarium are just over 200 years old and were collected by Robert Kaye Greville in 1821, who went on to publish the important journal ‘Scottish cryptogamic flora’. The collection also holds many other 19th century specimens from some of the biggest names in early mycological history like Elias Magnus Fries and Mordecai Cubitt Cooke, not to mention the extensive collections of expert 20th century mycologists.

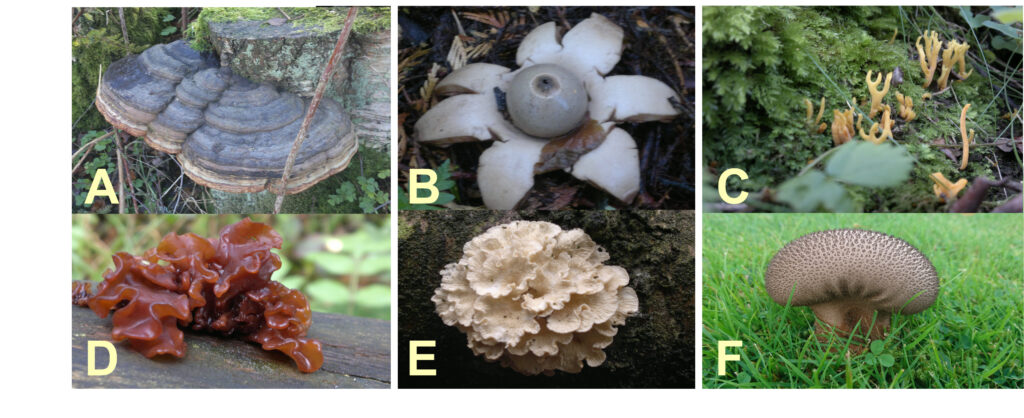

In addition to the classic mushroom shape, the RBGE collection of Basidiomycota includes many fungi that produce very different reproductive structures, some of which are shown here:

B. Geastrum triplex (Collared earthstar)

C. Clavulinopsis corniculata (Meadow coral)

D. Phaeotremella foliacea (Leafy Brain)

E. Plicaturopsis crispa (Crimped gill)

F. Lycoperdon nigrescens (Dusky puffball)