After Hortus Malabaricus: Sensing and Presencing Rare Plants

Published on behalf of Siân Bowen

The Project

Introduction

After Hortus Malabaricus: Sensing and Presencing Rare Plants marks the culmination of my four-year collaboration with the Herbarium at the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh (RBGE). Having held my first solo exhibition in Scotland at Inverleith House at RBGE in 1995, it is wonderful to be able to exhibit here once again.

In 2017, I was awarded a Leverhulme Research Fellowship to carry out the project. The Leverhulme Trust is known for supporting experimental proposals with an emphasis on outward facing journeys. The journey that the award facilitated has certainly been extraordinary – opening up possibilities to work with botanists, ecologists, historical researchers, cultural geographers, taxonomists and curators. It has allowed encounters with rare plants in darkened herbaria and light-filled South Indian forests and swamps; epistemologies used to ‘reveal’ specimens and sensory differences between plants’ live and preserved states.

Context

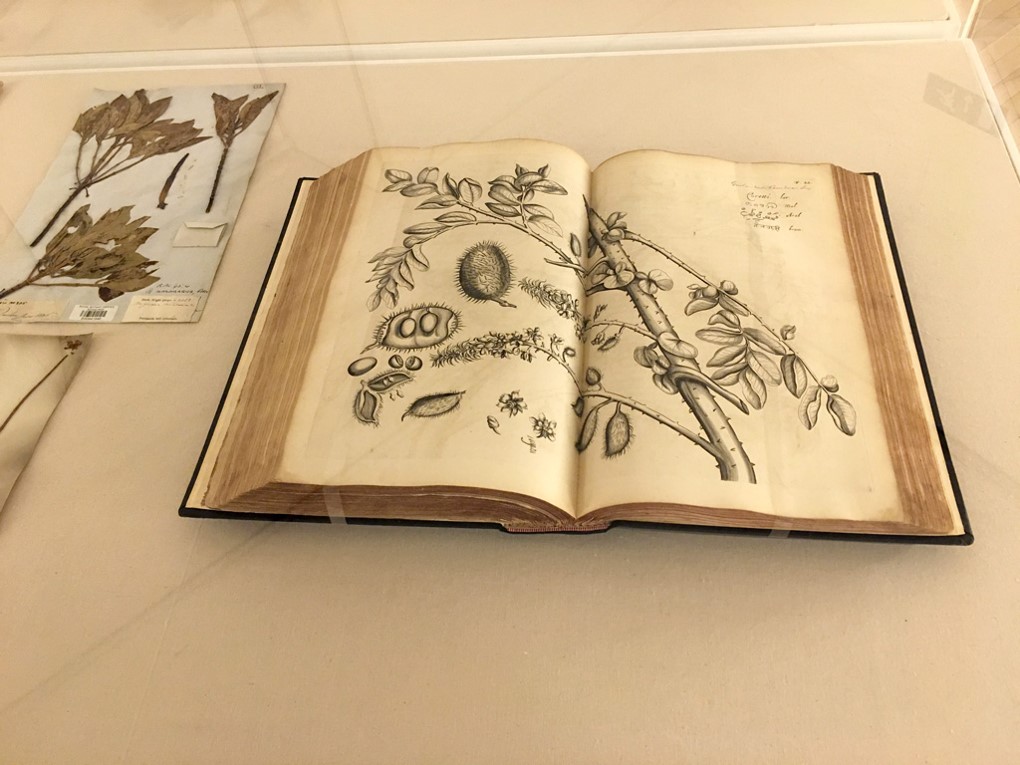

Plants have been a ‘currency’ of empires, their collection and distribution having had huge social, cultural and political implications. Marking RBGE’s 350th anniversary, After Hortus Malabaricus: Sensing and Presencing Rare Plants references the Garden’s rich historical Herbarium and archival collections, reflecting issues critical to our times. Plants brought from India to Edinburgh during the 19th century by Scottish surgeons, the extraordinary 17th-century illustrated treatise on plants of Malabar (current-day Kerala), Hortus Malabaricus, and living specimens in remote forests and coastal regions of Kerala, have all offered rich sources for enquiry. It was a great privilege to work with the extraordinary RBGE Herbarium and the insight of Dr Henry Noltie, RBGE Research Associate, has been invaluable throughout the project.

Hortus Malabaricus took nearly thirty years to compile. One of the earliest and most comprehensive accounts of Asian flora, it remained largely inaccessible until 2003, when it was finally published in English. Indian taxonomist K.S. Manilal spent over three decades completing this ground-breaking translation from Latin – together with his accompanying commentary on the current status of each plant in the region formerly known as Malabar.

Supported by experts in the UK and India, I sought to find the rarest plants described in Hortus Malabaricus – both as preserved historical specimens in the Herbarium and living plants in protected areas of Northern Kerala. The resulting drawings, videos, sound pieces, artist books, models and casts form a range of ‘collections’. These are titled to reflect sensory ways in which a group of objects that have been temporarily gathered together, might be encountered, considered and understood. They seek to prompt consideration of the fragile nature of plant life, the significance of a herbarium and the urgent need to protect our natural world – and make present the imperceptible nature of the vulnerabilities and resiliencies of rare plants.

with RBGE Herbarium specimen, Bruguiera cylindrica (L.)Bl.(Rhizophoraceae)

The Exhibition: Notes – Production & Installation

Collection: Sense & Collection: Sift

In the first room of the gallery, tables have been covered in layers of objects and fragments resulting from experimentation over the course of the four-year project. These reflect the wider concept of the exhibition which blurs boundaries between an artwork and its means of production – reflecting differing notions of the herbarium specimen as both scientific tool and object of aesthetic value and cultural significance. Preliminary models, casts, moulds and final works are given equal importance, prompting questions concerning concepts of experimentation and consolidation.

2017-19

Embossed paper; digital prints; dyed moulds, casts and papers; foil on book board; graphite; indigo; ink; laser engraved paper and acrylic; shellac; tracing paper; turmeric; wax and Victorian mirrors

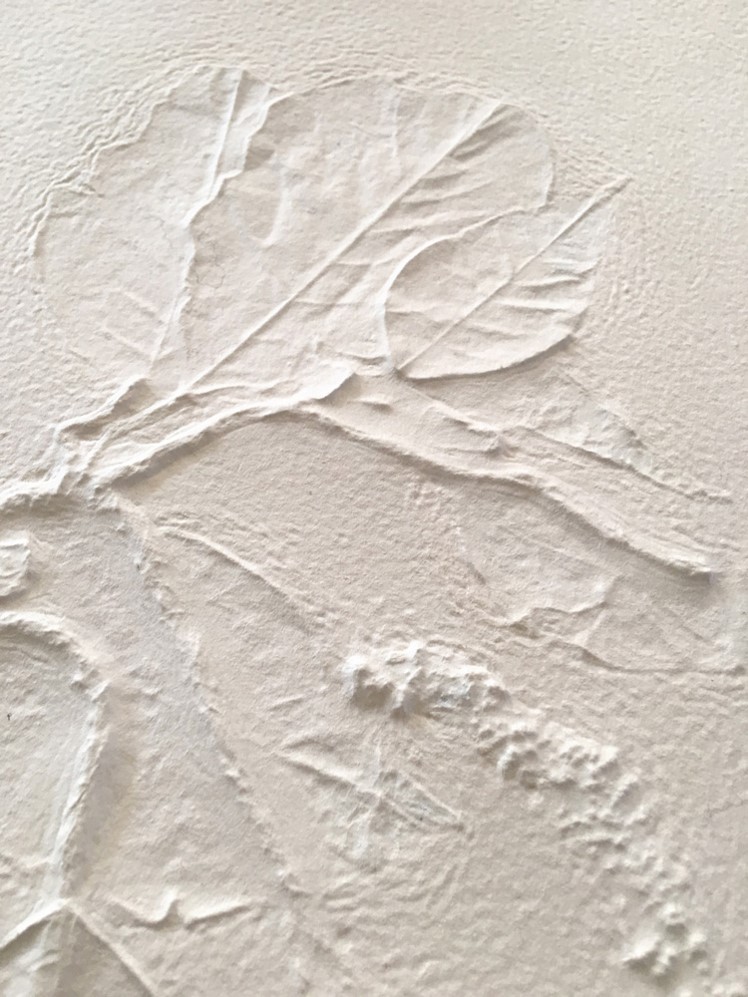

Intricate models in foil, paper and latex were made of eighteen RBGE historical Herbarium specimens – examples of plants in Hortus Malabaricus which are described by Manilal as ‘rare’ or ‘getting rarer’. In turn, I worked with modelmaker Gideon Bohannon to produce rubber moulds and dyed casts of these. And then with Belgian craftsman, Serge Pirard, to create a bespoke papermaking deckle and mould based on the 17th-century laid paper used in Hortus Malabaricus. Finally, I cast hemp pulp from the deckle and mould onto the rubber casts in order to produce the series, Collection: Sense. Both the flattened herbarium specimen and the imprint left on its drying paper, brings to the fore concepts of the relationship between image and object, and between two- and three-dimensionality. These aspects are explored through this group of blind-embossed paper casts.

2018-19

Paper casts from hemp pulp using a 17th-century replica papermaking mould and casts of models by the artist of herbarium specimens

The Bound Herbarium and Artist Books

Also exhibited are some of a number of artist books that I have been working on. Early historical herbaria took the form of bound volumes. These were often cut up during the 19th century and the mounted specimens were sold or exchanged, creating new collections. The artist books refer to this practice of binding and unbinding – cutting up, re-ordering and re-constructing. Discarded fragments from other works produced during the course of the project are interspersed and woven between the pages, which reveal laser-engraved images of models of herbarium specimens. The books also reveal reconstructed elements from images of 17th-century engravings, staged cutting and pinpricks into the surface of the paper and the residue of plant dyes.

The sensory relationship between sight and touch is explored not only through the nature of the books’ construction, but also through a range of other means. Indigo, shellac, wax, madder and catachu are amongst sustainable dyes and materials which invite different material and visual engagement. Contrast between crackle and silence when turning the pages, dependent on the choice of papers and their treatment, has been given consideration, as has the smoothness and roughness of the papers’ surfaces.

The works also reflect the unbound historical herbarium as a palimpsest – over decades, information on specimen backing papers was often re-assessed and subsequently, crossed out or added to. My interest in temporary systems of storage and labelling as a means to form new connections and narratives, also prompted the nature of these multi-faceted works.

2018-19

Book block: Embossing and laser engraving on burnished Indian hemp paper; graphite: kozo, hemp and jute papers; shellac; tracing paper; turmeric; indigo and wax

Cover: Indigo dyed kozo paper, letter press on hemp paper

Collaboration

In addition to working with a wide range of subject specialists including botanists, herbarium curators, forest gardeners, conservationists, cultural geographers and historical researchers, I also collaborated over a period of two years with artists Christopher Jones (UK) and Daniel Laskarin (Canada). A range of material was passed from artist to artist taking the form of an evolving collection. I engraved images of the models I had made of RBGE herbarium specimens onto the fragile gesso surfaces. Resolved components and production ‘debris’ were brought together in the final pieces. The fragility and somewhat tentative construction of these works reflects the key concepts of the project concerning ‘vulnerability’ and ‘resilience’.

2019

Collaborative works: Siân Bowen, Christopher Jones and Daniel Laskarin

Laser engraving, gesso, studio discards and found material

The Role of Light

Mirrors, reflective materials and media, light boxes and translucent supports are all employed to build on my ongoing interest in the relationship between the material and the ephemeral – and consider ways in which to interrogate a state of flux.

The relationship between the large Georgian windows of the gallery rooms, the scale of the interior space and the surrounding garden, create a very particular light environment; one which is constantly shifting and in turn, transforming the works. This, together with the journey made through the seven rooms, allowed a unique opportunity to consider a range of ways to install works in order to convey core concepts.

I wanted to create a contrast between the light environment of the ground and first floor galleries, offering a very different experience when moving through the space. Downstairs the blinds are open and natural light floods into each room, constantly interacting with the works in different ways. Upstairs on the other hand, the first blackout room of light box artworks, historical archival and herbarium material, leads through into three further blackout rooms showing a series of eight video works.

Field Recordings: Gurukula and Kadalundi

In search of living examples of the historical RBGE herbarium specimens, I carried out an artist’s residency at the remote Gurukula Botanical Sanctuary, set in the biodiverse, moist, deciduous rainforest. I then travelled to Kadalundi, a community nature reserve of mangrove forests. Field recordings were gathered and pieced together to reflect the way in which a notebook might evolve. At Kadalundi, I moved through the swamps in a small wooden boat – the sound of the bamboo steering pole against the side of the boat, passing trains and temple drums are combined with a high-pitched noise of screeching birds.

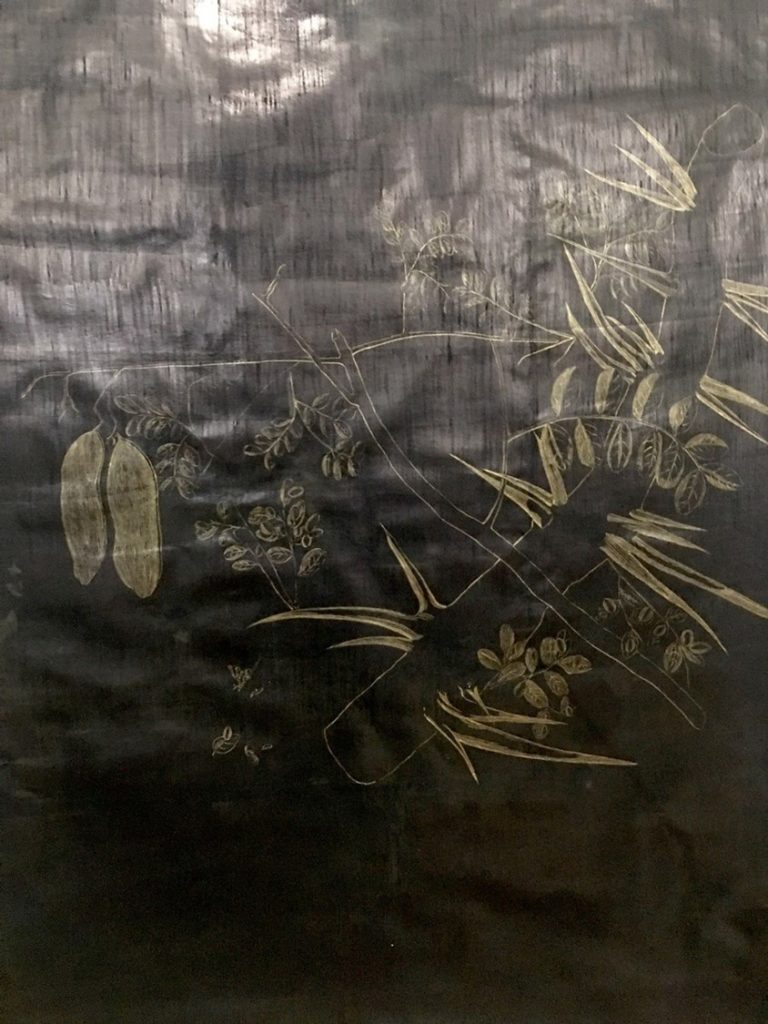

Burnishing Indigo and Bronze

My large-scale drawings in indigo and bronze pigments transcribe fragments of Hortus Malabaricus’ engravings. I repeatedly polished these works with an agate burnisher. As a result, the reflective images seem to disappear and reappear in the sheen of the drawings’ surfaces, echoing the precarious existence of the plants which they describe

2019

Burnished natural indigo pigment, powdered bronze and gum arabic on handmade gampi vellum paper

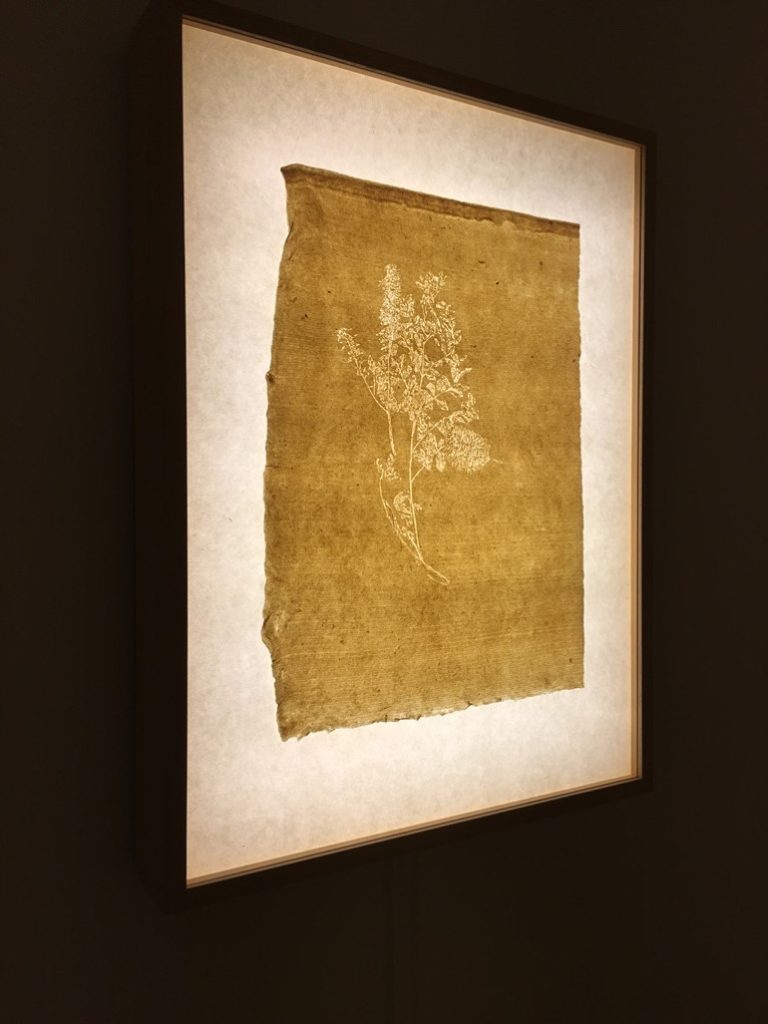

Laser Engravings, Nature Prints and Drying Papers

The relationship between the living plants in their native environment and pressed herbaria specimens has been a key aspect of my focus. Their shared fragility as material objects led to my production of a number of laser-engraved works; images of models that I made of herbarium specimens were burned into the top layers of the paper. The paper itself was produced in India by Hussein Kagzi. His family are amongst some of the last papermakers still using moulds woven from grass and who burnish the paper with a stone to create the smooth surface necessary for Indian miniature painting. The ambiguous relationship between object and image conveyed in 19th-century nature prints together with ghost-images of specimens left on their drying papers also informed these works.

2019

Lightbox with kozo paper and laser engraving on burnished Indian hemp paper

At Kadalundi Reserve & Artist Residency at Gurukula Botanical Sanctuary

A series of nine video works resulted from my artist residency in northern Kerala at the remote Gurukula Botanical Sanctuary, set in the biodiverse, moist, deciduous rainforest – and whilst travelling through the mangrove swamps of Kadalundi Reserve.

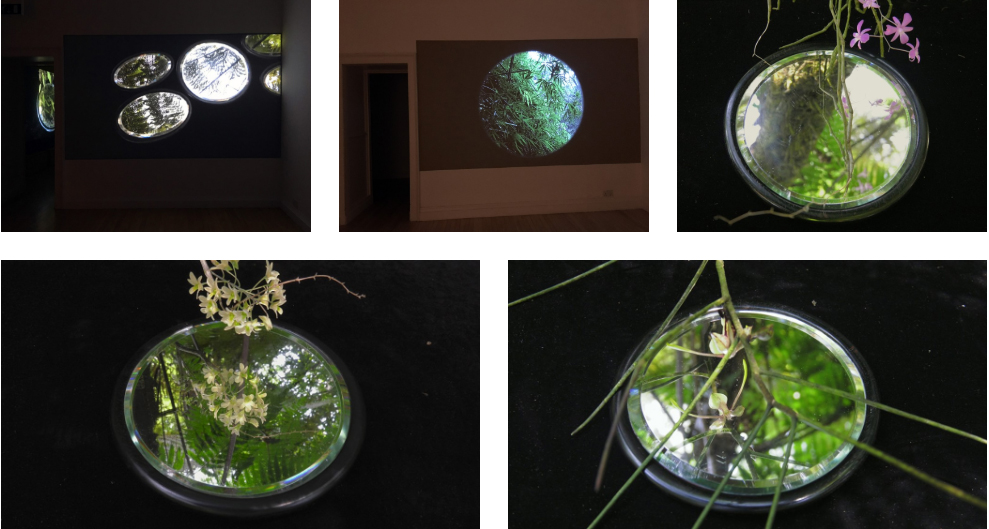

At Gurukula, I worked closely with local experts Suma Keloth, Sora Tsukamoto, Purvy Jain and Laly Joseph, to discover living examples of the rare plants identified as herbarium specimens. Fleeting reflections of these plants were then filmed in a group of seven Victorian hand mirrors, echoing both historical plant hunting and the ephemeral and elusive nature of the plants themselves. I also used a replica Claude glass (a historical black convex mirror), to create number of these works. The use of these mirrors encapsulates the vulnerable, jewellike quality of indigenous forest orchids and other rarely seen plants. At Kadalundi, whilst travelling in a small wooden boat, I filmed the reflection of the mangroves in the Claude glass which was suspended over the boat’s side.

The employment of mirrors both focuses on, and distances us from, the threatened mangrove forests and tiny forest flora. As I moved through these natural environments, the mirror seemingly gathers a collection of rare plants and in doing so, challenges our experiential understanding of time and space.

2019

Stills from a series of eight video works, UHD, looped

For further details about the project including an accompanying micro-conference, Sensing and Presencing the Imperceptible, please see: sianbowen.com

The project has been generously supported by a Leverhulme Research Fellowship (2017-19) and Arts University Bournemouth. It also forms part of the international programme, EXTRACTION: Art on the Edge of the Abyss.

Manoj Pande

Wonderful … Amazing work done .. ..thanks for sharing your journey and findings of your research . Best wishes