H.J. Noltie

When the museum and library of the East India Company (EIC), following its inheritance by the India Office of the British government, was dispersed in 1879 its fragments were scattered between many institutions. These included the British and South Kensington Museums. With renamings and further institutional splittings, the fine and applied art collections, the zoological material, and the voluminous manuscript records of the EIC, are now to be found in the V & A, the BM, the Natural History Museum and the British Library. In 1879, and not without considerable acrimony, Kew received all the botanical material – in vast quantities. Among the economic botanical material were 36 tons of wood samples (largely subsequently destroyed), and from the library some 3359 botanical drawings.

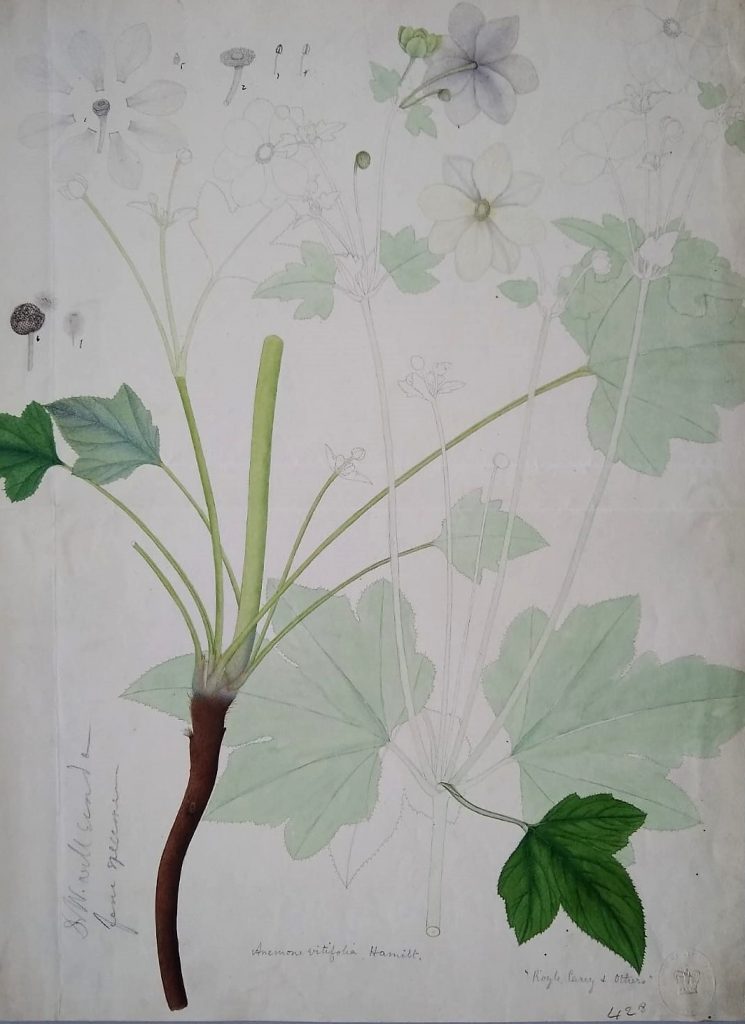

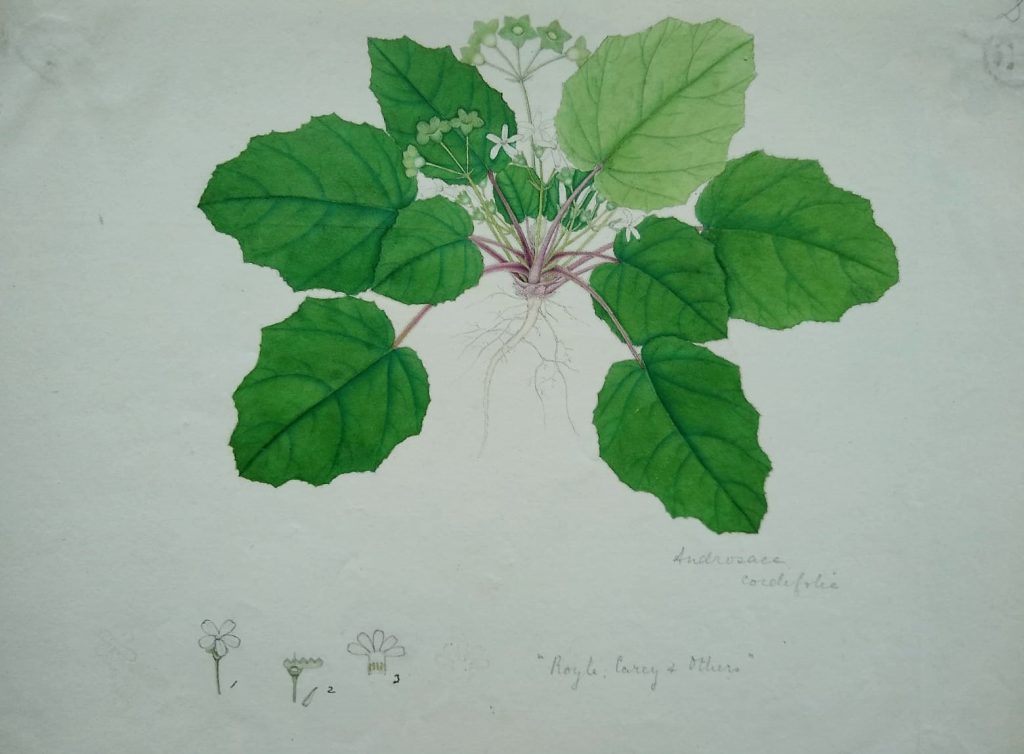

Of the drawings 1791 were grouped under the cobbled-together title ‘Royle, Carey & Others’ (RCO) – something of a misnomer, as pointed out in my last blog. With recent work at Kew, and subsequent follow-up at RBGE, it has emerged that approximately 1200 of these were made for Nathaniel Wallich, about 400 for John Forbes Royle at the Saharunpur Botanic Garden, and 100 for Francis Buchanan on his Bengal Survey. ‘Carey’ proves to be a red herring: none of the drawings has anything to do with the botanical-missionary the Rev William Carey, the surname being a mistranscription for that of Thomas Casey, a temporary holder of the Calcutta Superintendent’s post in 1816 who probably had a hand in sending some of the drawings to the India Library. It is now clear that the drawings should really have been designated the ‘Wallich, Royle and Buchanan’ collection.

When Kew received this almost overwhelming influx of material it was generous in distributing what was considered ‘duplicate’ material to other institutions. In the 1890s RBGE received several such batches, including about 50 RCO drawings. In 1998 this was one of many distinct collections that I separated out from the 250,000 sheets of our Illustrations Collection; embarrassingly, it has taken me until now to undertake further work on them. Not that I was entirely idle over the intervening two decades, but had decided to concentrate on elements of the collection that seemed to be most closely connected with RBGE – notably the collections of three notable Garden alumni, Alexander Gibson, Robert Wight and Hugh Cleghorn. My work always seems to result in the finding of hitherto unexpected connections, as shown with the identification of the Buchanan Bengal Survey drawings. It was now time to turn attention to the 38 drawings annotated in Nathaniel Wallich’s untidy scrawl. I had always been vaguely aware of their significance and reproduced two of them in my first exhibition and related catalogue of the Edinburgh collection. These were of Aconitum ferox and Valeriana hardwickii painted for Wallich by Vishnupersaud and reproduced in his sumptuously illustrated, elephant-folio Plantae Asiaticae Rariores (PAR), in which the Indian artists’ drawings were somewhat reconfigured by the Maltese lithographer Maxim Gauci.

In the introduction to PAR, Wallich explained that when he travelled to London on leave from Calcutta in 1828, he took with him 1200 drawings, made by the team of artists at the Calcutta Garden (following the tradition of his predecessors Roxburgh and Buchanan). While many of these were made in the Garden, based on plants introduced there from S and SE Asia (including especially Silhet and Nepal) some were made by the artists who accompanied Wallich on his excursions to Nepal (1820/1) and Burma (1826/7). The drawings formed a very minor part of his baggage, which consisted of 20 tons of herbarium specimens packed in 30 barrels, 52 chests and 12 cases of living plants. Based in Frith Street, Soho, he spent the next four years curating and cataloguing the specimens and coordinating the production of his magnificent book. In this he was helped by a team of specialists working on particular families, which included Robert Graham, Regius Keeper of RBGE, who worked on the legumes. The specimens were identified and named (7683 species in this initial curation), sorted into 226,000 duplicates and distributed widely in 66 sets (of varying degrees of completeness). The top set was kept in London, presented by the EIC to the Linnean Society, which in turn gave it to Kew in 1912, where it remains in its original mahogany cabinets. Wallich’s own lithographed ‘Numerical List’ (usually known as the ‘Wallich Catalogue’) of the herbarium, which contains material from localities stretching from Kumaon to Singapore, contains details of the collections, each species having a number, with supplementary numbers or letters in cases where species were represented by more than one collection.

What few have previously realised is that the Wallich drawings are – hardly surprisingly – intimately connected with his herbarium specimens. While the drawings bear no collecting details, only a plant name, it is possible to link them not only with the 300 reproduced in PAR but, in many cases, with specimens in the Wallich Herbarium. Some of the drawings will therefore prove to be part of the original material (‘types’) of new species based on such specimens.

The material on which the 38 drawings that have come to rest in Edinburgh, and their publication record, has been a revelation, not least with regard to the RBGE’s current major project on the Flora of Nepal. Of the drawings from the RCO working set eight were published in PAR and one, at least in part, in Wallich’s Tentamen Florae Napalensis. Of these, from attributions on the printed plates, two are by Vishnuprasad and seven by Gorachand. When it comes to the sources of the plants, and where the drawings were made, care must be taken due to lack of evidence written on them. However, up to 17 were probably based on Nepalese material, of which nine certainly, and two probably, were made in the Calcutta Garden between 1817 and 1820 from material sent by Edward Gardner. Six of the drawings could, just conceivably, have been among the 364 known to have been made in Nepal during Wallich’s expedition of 1820/1, but lack the informative watermark or, through trimming, have lost what would have been a diagnostic number in the top right corner. The other drawings were probably made in the Calcutta Garden, for which the biggest single source was the Khasia Hills (‘Montes Sillet’) of plants sent by Matthew Smith. Of the two drawings at RBGE from Wallich’s 1828 EIC presentation set, based on drawings in the working RCO collection, one is based on a drawing made in Nepal (Colquhounia coccinea) in 1821, the other (Dysolobium grande) in Burma in 1826/7.

Eriocapitella vitifolia

Potentilla lineata

Primula filipes

This updated and corrected version replaces a blog originally posted on 4 December 2018.