India does not spring immediately to mind as a major source of plants for British gardens. The reason for this is largely environmental – as the larger part of India lies within the tropics, plants from these areas must be grown under glass in temperate Britain. However, the mountainous parts of northern India include substantial parts of the Himalayan range. While many Himalayan plants have been introduced from Nepal and China, introductions of temperate plants, hardy in British gardens, have been made from three Indian areas: the NW Himalaya (the states of Jammu & Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, and Uttarakhand, especially the districts of Kumaon and Garhwal), Sikkim and Darjeeling in the Eastern Himalaya, and the north-eastern states formerly loosely known as ‘Assam’.

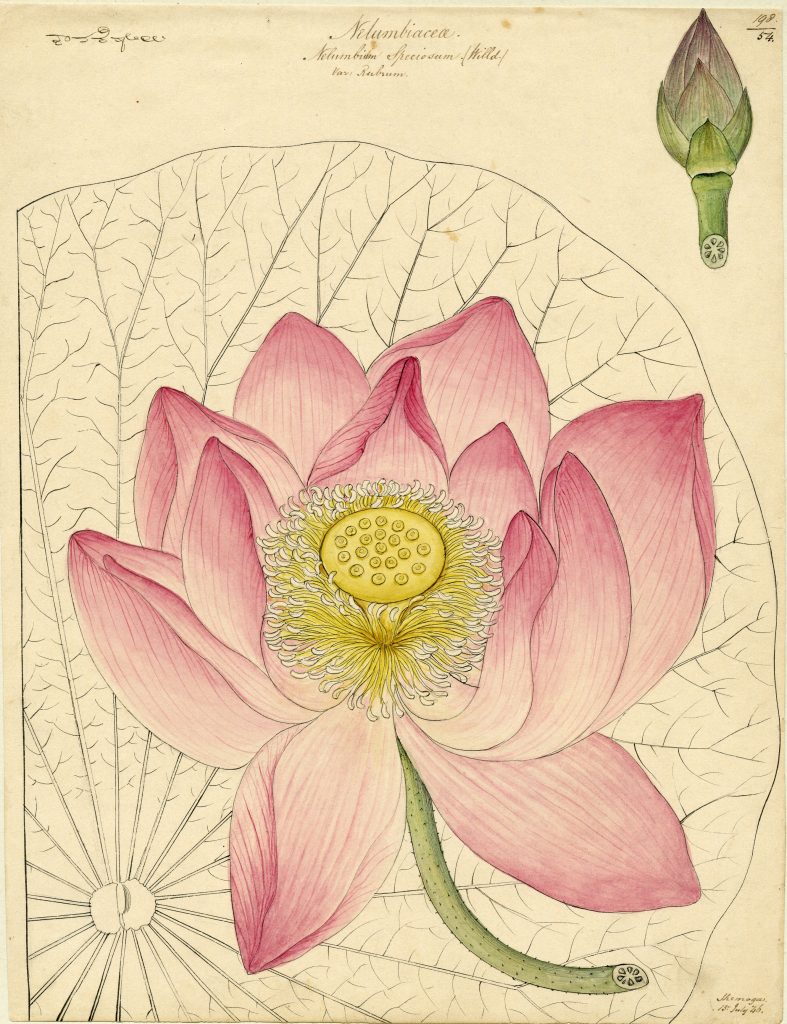

Historically speaking, the original interests of the British (preceded by the Portuguese and Dutch) were with the tropical parts of the Subcontinent – for spices and other plants of economic importance. It was thus, rather surprisingly, tropical plants that were the first to be introduced – as early as the seventeenth century. As these had to be grown in hothouses this was restricted to the gardens of certain wealthy individuals and a few institutional botanic gardens. The first record of an Indian plant growing at RBGE occurs in James Sutherland’s 1683 catalogue of the Garden – the grass Job’s tears (Coix lacryma-jobi). Coix had been cultivated by John Gerarde in London a hundred years earlier and came to him via Italy, so the link with India is probably very indirect. The Dutch were among the pioneers of Indian botanical exploration and plants were sent back to the botanic gardens of Amsterdam and Leiden from the late seventeenth century onwards. Charles Alston (Regius Keeper of RBGE, 1716–60) studied under Boerhaave in Leiden and must have seen Indian plants growing there and possibly brought some back to Edinburgh. Certainly John Hope (Regius Keeper, 1761–86) grew some Indian plants (when the Garden was in Leith Walk) and even conducted physiological experiments on them. Hope was interested in the leaf movement of legumes and studied sleep movements in leaflets of the tamarind (Tamarindus indicus) and the diurnal movements of the telegraph plant (Codariocalyx motorius). Much work remains to be done on the history of Indian plants in the RBGE, but large numbers certainly began to arrive in the time of Robert Graham (Regius Keeper, 1819–1845). These were tended by his gardener William McNab. Graham was a friend of Nathaniel Wallich, who distributed plants from the Calcutta Botanic Garden widely. Some of these Graham described as new species in the Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal and Curtis’s Botanical Magazine.

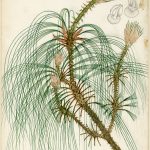

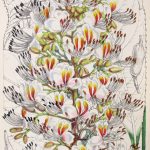

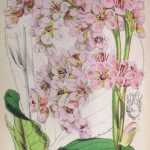

The exploration of the Himalaya may be said to have started with Hope’s pupil Francis Buchanan (Buchanan-Hamilton) who in 1802 was the first western botanist to make a detailed study of the flora of Nepal. This continued with visits to Nepal by Wallich in the 1820s. It was the influential John Lindley (of the Horticultural Society and later Professor of Botany at the University College, London) who realised the importance of the Himalaya as a source of hardy plants for British gardens. This led to a steady stream of introductions from the 1830s onwards by amateurs (such as Lady Amherst), botanically inclined soldiers (such as Thomas Hardwicke and Edward Madden) and by professional botanists including John Forbes Royle and plant collectors such as Thomas Lobb. The culmination of this phase came with Joseph Hooker’s expedition to Sikkim in 1848/9, which literally changed the face of Scottish gardens, with the first steps towards large-scale introduction of rhododendrons and to a lesser extent of primulas (Primula sikkimensis) and Himalayan poppies (including Meconopsis simplicifolia). Hooker also visited the Khasia Hills (now in Meghalaya) and, along with the plant collector Thomas Lobb, became aware their richness – especially for orchids.

In the twentieth century Himalayan imports from India reached a new peak, perhaps in competition with the craze for Chinese plants. Roland Edgar Cooper and George Herbert Cave introduced plants from Sikkim, as did Frank Ludlow and George Sherriff (whose major work, however, was in Bhutan and Tibet). Frank Kingdon-Ward collected extensively in ‘Upper Assam’ in what are now the states of Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland and Manipur, building on the work of pioneers such as Gustav Mann.

A note of warning: many plants with ‘India’ in their common or Latin name are misnomers; for example the Indian shot (Canna indica) comes from South America, and the Indian bean tree (Catalpa bignonioides) is native to south-eastern USA. Others have names from a time when the whole region east of Arabia (including India, Indo-China, Malaysia and Indonesia) were known as the ‘East Indies’, especially in early times when the exact origin of a plant was not considered very important, or had been confused.

Currently about 700 Indian species are grown at RBGE, although the wild distribution of most of these is not restricted to India. The collection is particularly strong in Himalayan plants, mirroring RBGE’s research interest in the Sino-Himalayan region.

Dr. P.T. DEVARAJAN

Gives appreciable details of plants in India by British